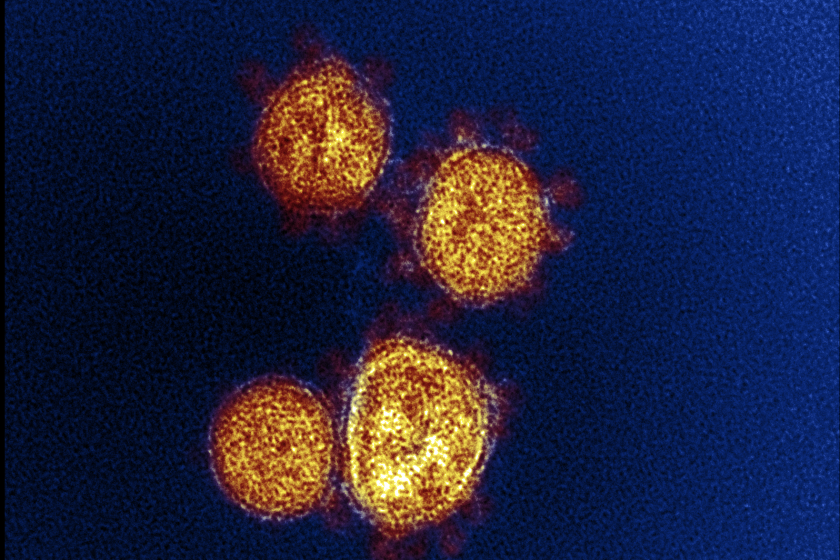

COVID vaccines still work against Delta variant, study says

New research from France adds to evidence that widely used COVID-19 vaccines still offer strong protection against the Delta variant of the coronavirus that is spreading rapidly around the world and now is the most prevalent strain in the U.S.

The Delta variant is surging through populations with low vaccination rates, causing hospitalizations in those areas to rise, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said Thursday.

“This rapid rise is troubling,” she said. A few weeks ago the Delta variant accounted for just over a quarter of new U.S. cases, but it now accounts for just over half — and in some places, such as parts of the Midwest, as much as 80%.

Meanwhile, highly immunized swaths of America are getting back to normal, Walensky said.

Researchers from France’s Pasteur Institute reported new evidence Thursday that full vaccination is critical.

In laboratory tests, blood from several dozen people who received only their first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech or AstraZeneca vaccines “barely inhibited” the Delta variant, the team reported in the journal Nature.

But weeks after getting their second dose, nearly all had what researchers deemed an immune boost strong enough to neutralize the Delta variant — even if it was a little less potent than against earlier versions of the virus.

Scientists have found 13 places in the human genome that may influence our susceptibility to a coronavirus infection or risk of severe COVID-19.

The French researchers also tested unvaccinated people who had survived a coronavirus infection and found their antibodies were four-fold less potent against the Delta variant. But a single dose of vaccine dramatically boosted their antibody levels — sparking cross-protection against Delta and two other variants, the study found.

The finding supports public health recommendations that COVID-19 survivors still get vaccinated rather than rely on natural immunity.

The lab experiments add to real-world data that mutations in the Delta variant aren’t allowing the strain to evade the vaccines most widely used in Western countries.

A past coronavirus infection may eliminate the need for a second dose of COVID-19 vaccine, a growing body of evidence suggests.

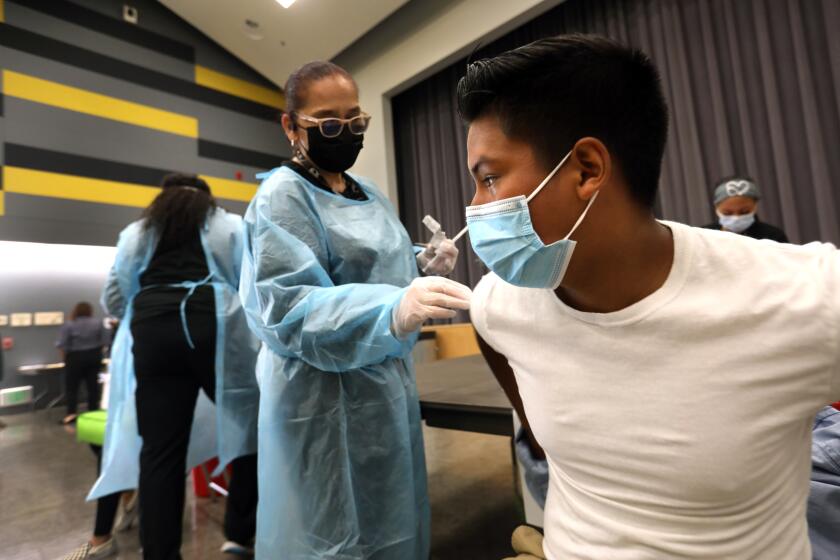

Researchers in Britain found that two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, for example, are 96% protective against hospitalization in cases involving the Delta variant and 88% effective at preventing COVID-19 symptoms altogether. That finding was echoed last weekend by Canadian researchers, while another report from Israel suggested protection against mild symptoms may have dipped lower, to 64%.

Whether people who are fully vaccinated still need to wear masks in places where the Delta variant is surging is a growing question. In the U.S., the CDC maintains that this isn’t necessary, but health officials in Los Angeles County now recommend that everyone wear masks in indoor public spaces, regardless of vaccination status.

The new experiments from France underscore the need to get people around the world immunized as quickly as possible, before the virus evolves even more and potentially becomes more resistant to vaccines or treatments, experts say.

A new CDC report on “breakthrough” infections in people who have been vaccinated against COVID-19 finds that just 2% of such cases result in death.

COVID-19 vaccines didn’t work perfectly even before the Delta variant came along, but the best evidence suggests that if vaccinated people become infected with the coronavirus, they’re much less likely to become seriously ill.

“Let me emphasize, if you were vaccinated, you have a very high degree of protection,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, the U.S. government’s top infectious disease expert, said Thursday.

In the U.S., case rates have been rising for weeks and the rate of hospitalizations has started to tick up, rising 7% from the previous seven-day average, Walensky said.

However, deaths remain down on average, which some experts believe is at least partly due to high vaccination rates in people 65 and older — a group that’s particularly susceptible to severe disease.

Associated Press writer Mike Stobbe contributed to this story.