Studies of hospital workers suggest COVID-19 vaccines really do prevent coronavirus infections

The COVID-19 vaccines being administered in the U.S. were authorized for use because they dramatically reduced the risk of getting the disease when tested in clinical trials. However, those trials didn’t test the vaccines’ ability to prevent a coronavirus infection — the first step on the road to COVID-19.

Scientists suspect the vaccines thwart infections to some extent. Two new studies bolster their case.

Both studies compare coronavirus infection rates among vaccinated and unvaccinated people who work at a single medical center. And in both cases, being vaccinated was indeed associated with a significantly lower risk of testing positive for an infection.

Hospital employees make good study subjects because they were among the very first people to get access to COVID-19 vaccines. That means they have a longer track record to mine when it comes to assessing the performance of the shots.

Another upside: Many hospitals routinely screen their workers for coronavirus infections. That makes it possible to identify people who seem perfectly healthy but harbor the SARS-CoV-2 virus in their system — and have the potential to spread it to others.

Unlike in a clinical trial, the hospital workers in these two studies decided for themselves whether to get the COVID-19 vaccine or not. There was nothing random about it.

That means that if coronavirus infection rates are different between vaccinated and unvaccinated workers, it might be due to factors other than the vaccine itself. Perhaps the people who made a point of getting the shots were also more likely to wear masks, wash their hands thoroughly or take other actions to avoid getting sick.

Still, until better data are available, studies like these can provide some insight into whether COVID-19 vaccines prevent infections as well as disease.

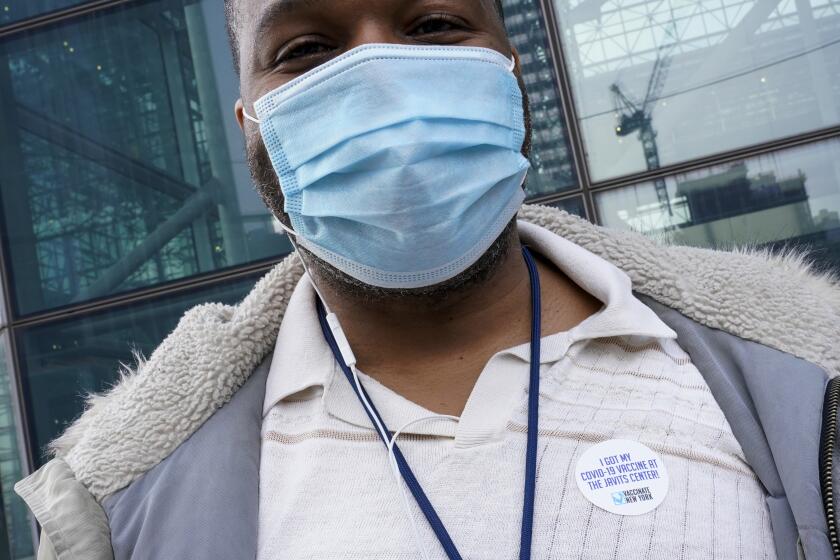

U.S. health officials see two kinds of people: Those who are vaccinated and those who aren’t. They’re trying to get unvaccinated Americans to switch sides.

The first report comes from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., where workers started getting the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine Dec. 17. By March 20, 3,052 workers had received at least one dose, including 2,776 who got both doses. An additional 2,165 workers who were eligible for the vaccine declined to take it.

Over the three months, 51 people tested positive for a coronavirus infection after receiving their first dose of vaccine, and 29 of them never developed any COVID-19 symptoms. Meanwhile, 185 of the unvaccinated people became infected, and 79 of them were asymptomatic.

After crunching all the numbers, biostatistician Li Tang and her St. Jude colleagues determined that people who’d had at least one dose of vaccine were 79% less likely than their unvaccinated coworkers to become infected with the coronavirus. They were also 72% less likely to develop an infection that was asymptomatic.

This apparent protection was more powerful in people who got both doses of the vaccine and had time for that second dose to kick in. Hospital workers who were at least seven days out from their second shot were 90% less likely than their unvaccinated counterparts to become infected, and when they did, their infections did not produce symptoms.

Long before the blood clots, there were fears the Johnson & Johnson vaccine was a second-class shot compared with Moderna or Pfizer.

The second study took place at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center in Israel, where workers started getting the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine Dec. 20. By Feb. 25, 5,953 of them had received at least one dose, and all but 436 of them had gotten both doses. An additional 757 workers remained unvaccinated.

Altogether, these workers were tested for coronavirus infections 16,224 times, and 243 of those tests came back positive. In 149 of those cases, the infection led to COVID-19 symptoms — 64 of them in people who had been vaccinated and 85 in the much smaller group of those who hadn’t.

Researchers led by Dr. Yoel Angel calculated that people who were fully vaccinated were 97% less likely than their unvaccinated peers to develop an infection with symptoms. Even among those who were only partially vaccinated, the risk of a symptomatic infection was 89% lower.

Sixty-three people who’d had at least one dose of vaccine were found to have asymptomatic coronavirus infections, as were 31 workers who skipped the vaccine.

The researchers calculated that people who were fully vaccinated were 86% less likely than their unvaccinated counterparts to develop an asymptomatic infection. Even those who had only one dose of vaccine saw their risk fall by 36%.

An up-close view of how the coronavirus infects cells in the brain and spinal cord helps explain the neurological symptoms of some COVID-19 patients.

The findings about asymptomatic infections are particularly important because people who have SARS-CoV-2 and don’t know it are thought to make up somewhere between 40% and 45% of coronavirus cases — and they could be spreading the virus to others without realizing it, Angel and his colleagues wrote.

In other words, the study results suggest that COVID-19 vaccines have the potential to greatly reduce the threat posed by “silent spreaders.”

Both studies were published Thursday in the Journal of the American Medical Assn.