Haves vs. have-nots: Who ‘deserves’ to be next in line for the COVID-19 vaccine?

The arrival of COVID-19 vaccines is about to create a new list of haves and have-nots.

Over the next few months, some Americans will gain the protection conferred by a jab or two in the arm. Others will have no choice but to wait.

Healthcare in the United States has long gone first to those able to pay. But the scarcity of vaccines may upend that formula.

Public health experts and medical ethicists have consistently urged state and local officials to allocate early allotments of vaccine to essential workers, imprisoned populations and people whose weight and poor health behaviors have put them at greater risk of becoming seriously ill with COVID-19. Members of racial and ethnic minorities should also be entitled to priority access as a step toward making up for generations of health disparities, the ethicists say.

But Americans asked to wait their turn may not always be pleased to see who’s in line ahead of them.

“There will probably be controversy,” said Dr. Peter Szilagyi, a UCLA pediatrician who serves on the panel that advises the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on vaccines.

Szilagyi said he has watched in distress as rifts over who most deserves Americans’ compassion and protection have been exposed.

“The measure of a country is how it treats its most vulnerable, and one measure of that is how well we allocate the vaccine over the next few months,” he said. “This is an opportunity for us to be each others’ keepers and to not think about ourselves first.”

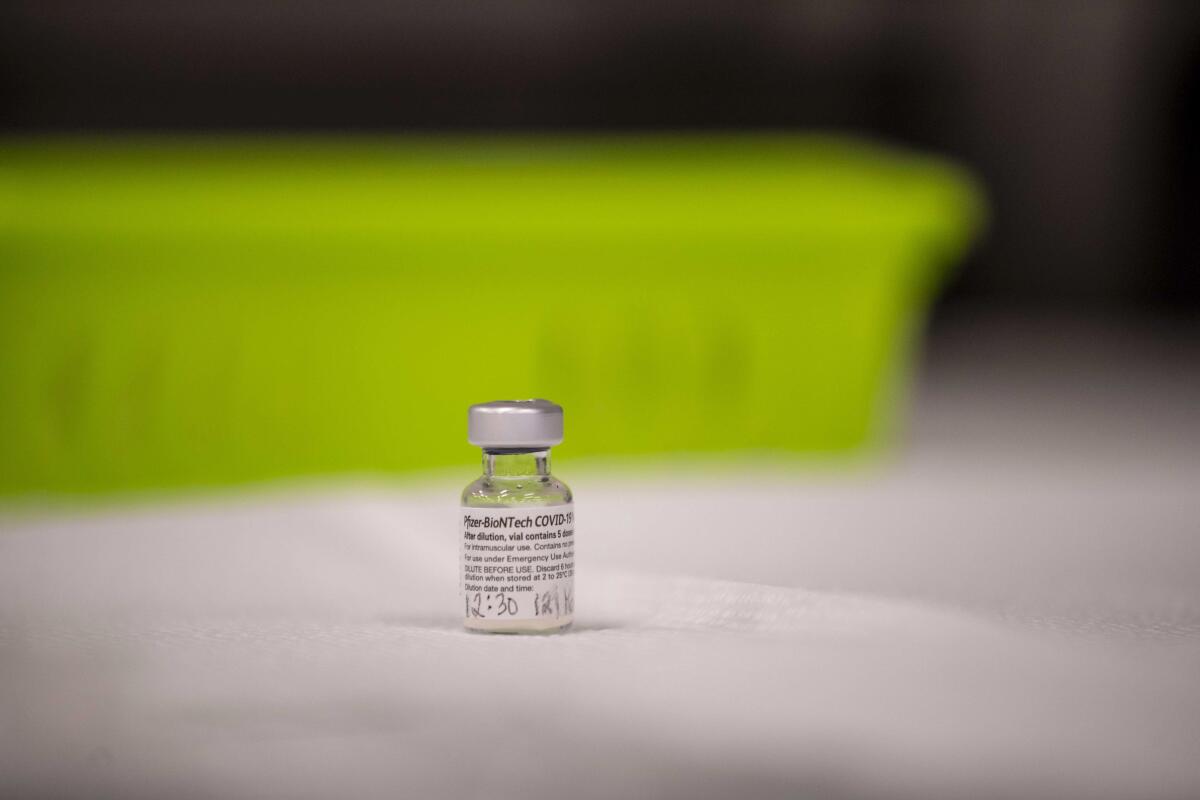

This much is not controversial: Beginning this week and well into January, some 21 million healthcare workers and 3 million people living in nursing homes and other residential care facilities will get the first doses of highly protective vaccines made by either Pfizer and BioNTech or Moderna and the National Institutes of Health. The first group earned its spot by being a critical workforce with an unavoidable level of exposure; the second group did so by absorbing 38% of the nation’s roughly 314,000 COVID-19 deaths.

COVID-19 vaccines may not be particularly effective in the elderly residents of long-term care facilities. A look at why they are getting them first.

Of the remaining 230 million U.S. adults, 18% have said they definitely would not get vaccinated, according to a late November poll by the Pew Research Center. That leaves close to 190 million adults vying for doses that could fully vaccinate just 76 million people by the end of March. They are waiting, and wondering when their turn will come.

Many among them could reasonably stake a claim to be next in line.

The roughly 66 million workers who supply food, drive buses and keep necessary goods and services flowing must show up for work — and risk infection — if the economy is to keep operating. An estimated 100 million in the United States have medical conditions — such as asthma, heart disease, severe obesity and a history of smoking — that make them more vulnerable to serious disease or death if infected. And roughly 50 million Americans age 65 and older face poorer outcomes if they catch COVID-19, due to their age.

Even experts acknowledge that, after healthcare workers and nursing home residents, it’s hard to say who should come next. The power to decide lies with state and local authorities, and at those levels, goals will vary.

Should vaccine be allocated in ways that reduce COVID-19 deaths or that drive down new infections? Should it be used to get the economy back on track, or to redress longstanding health inequities? Have some people forfeited the chance to get vaccinated early because their own bad decisions landed them in a high-risk group?

A data analysis performed for the CDC offers answers to at least two of those questions.

In a scenario where the pandemic is still growing, as it is now, quickly vaccinating “essential workers” — who are younger and circulate widely — would likely reduce infections 1% to 5% more than expending scarce vaccine on seniors first, the analysis found.

The model also suggests that infections would fall by roughly the same amount — 1% to 5% — if vaccine is prioritized for those with medical conditions that complicate the course of COVID-19.

Though both of those strategies would blunt the rise in infections, neither would drive down COVID-19 deaths as effectively as a third option: vaccinating everyone 65 and older. Giving seniors, including those in care facilities, vaccine priority would reduce the death toll by as much as 4%, the CDC’s model suggested.

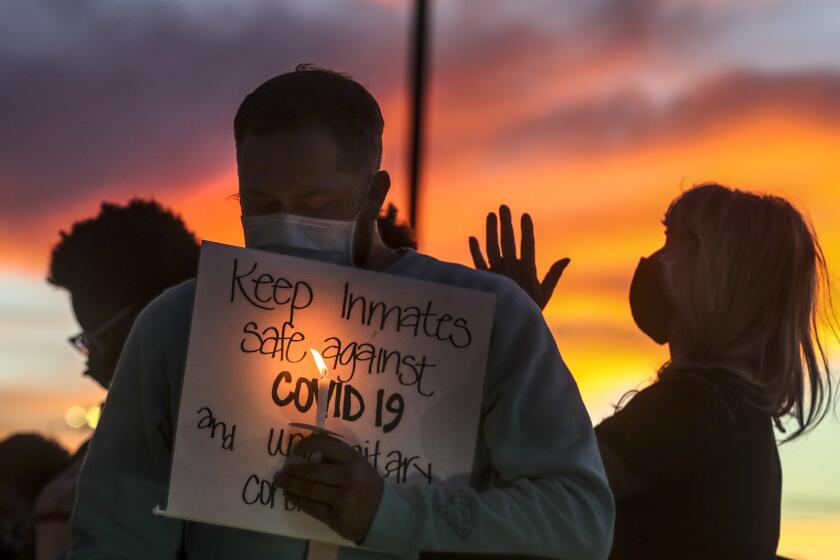

And then there are prisoners. Many public health experts and medical ethicists have argued that incarcerated persons should be vaccinated alongside correctional officers, who are likely to get their shots early as members of the “essential critical infrastructure workforce.”

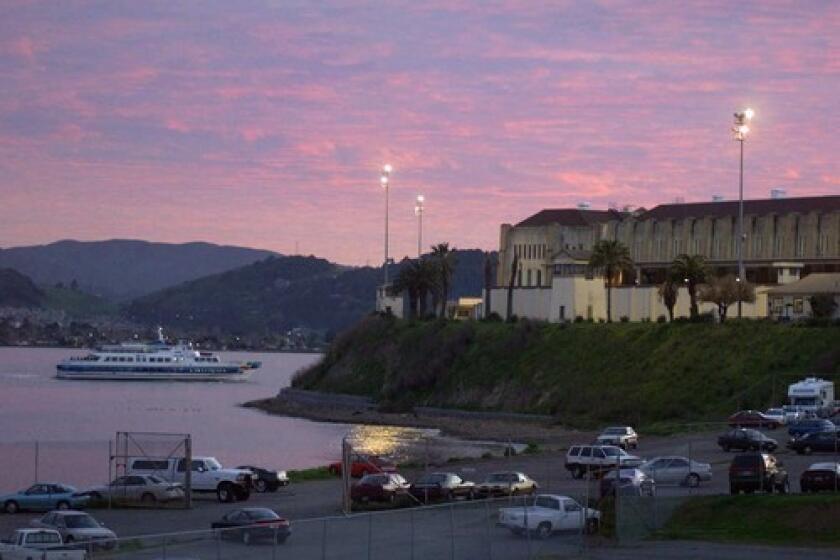

Like the residents of nursing homes, the roughly 2 million people in state and federal prisons and immigration detention centers have no control over the entry of coronavirus into their midst. In crowded lockup conditions, they can’t choose to maintain distance from others to prevent catching the virus. And, like essential workers, they’ve been disproportionately infected when the virus begins circulating within the walls that confine them.

Nationwide, more than 249,000 inmates have tested positive and at least 1,500 have died from COVID-19 since last March.

An effort by UCLA Law School to gauge the pandemic’s impact in the U.S. found that in a nine-week period ending in early June, people incarcerated in state and federal prisons were 5.5 times likelier than the general population to be infected with the coronavirus. After taking account of their age and sex, they also found the nation’s prisoners were three times more likely to die of COVID-19 than those living outside.

Roughly 20 prisons and immigration detention centers have become COVID-19 hot zones, said Sharon Dolovich, a UCLA law professor who directs the school’s COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project. Prison outbreaks have helped fill rural hospital beds to capacity. Correctional officers move between prisons and communities, sustaining transmission both inside and out.

In September, these vulnerabilities led a panel convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine to recommend that prisoners be included in “Phase 2” of the vaccines’ rollout, alongside essential workers, teachers and those with medical conditions that confer a moderate risk of severe COVID-19 illness.

States that have planned to place prison populations in line to get vaccine in the coming three months include California, North Carolina, Maryland, Delaware, Utah, New Mexico, Nebraska, Montana and Massachusetts.

Colorado’s health department also drew up plans to give prisoners priority. But Gov. Jared Polis dismissed the effort to vaccinate incarcerated adults before independently living seniors and adults with serious health conditions.

“There’s no way it’s going to go to prisoners before it goes to people that haven’t committed any crime,” Polis said. “That’s obvious.”

Prisons are COVID-19 epicenter; justice commission recommends inmate releases, early vaccinations.

Politicians reared on decades of tough-on-crime rhetoric may find the case for vaccinating prisoners early a tough sell, Dolovich said. But even if they are unpersuaded by compassion for their fellow citizens or their obligation to protect prisoners in their care, she said there are strong public health arguments for ensuring they are vaccinated when the men and women who guard them get theirs.

“It’s a petri dish of infection,” Dolovich said. “If we want to control the spread, we have to recognize that prisons and jails are central sources” of infection that must be tamed.

The debate over prisoners reflects a larger national discussion touched off by the pandemic, said Harald Schmidt, a University of Pennsylvania researcher who studies the interplay between personal responsibility and public health.

In every state, politicians accustomed to disbursing scarce resources in a way that simply maximizes benefits are now facing a decision in which issues of fairness and social justice are expected to get equal billing with the aims of stopping a pandemic and restarting an economy.

That will require a willingness to acknowledge that Americans with special vulnerabilities to COVID-19 — including obesity, smoking, incarceration or poverty — do not bear full responsibility for their risk factors. It is a group’s vulnerability that entitles its members to vaccine priority, not how they got it.

“The penalty we put on people in prison is prison, not that we withdraw healthcare or protections from them,” Schmidt said. “The purpose of an allocation system is not to mete out additional penalties. It’s to stop the pandemic.”