How the blood of coronavirus survivors may protect others from COVID-19

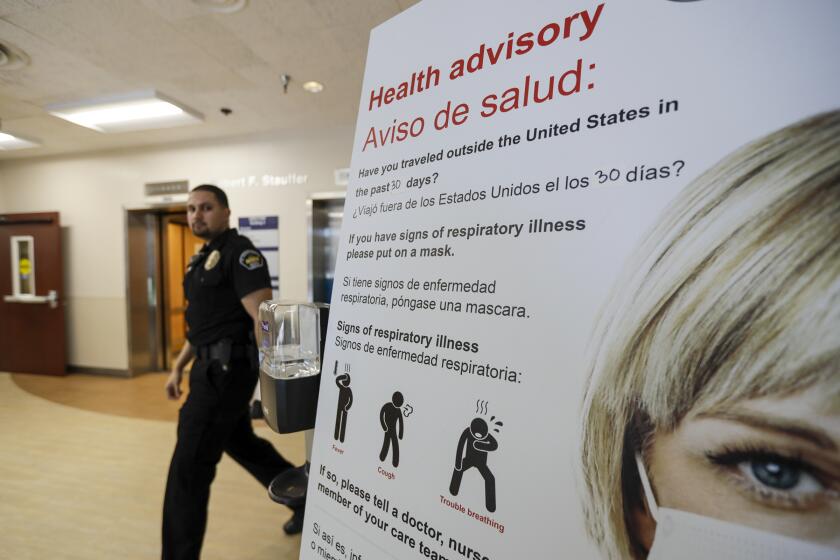

As U.S. scientists race to stave off a tidal wave of COVID-19 patients, they are showing renewed interest in a little-known medicine with ancient roots and many modern applications: convalescent plasma.

It’s medicine now coursing through the veins of at least 86,690 people in China and elsewhere, all of whom have joined a fraternity of potentially powerful healers. These are people who have been infected with the novel coronavirus and survived.

Scientists believe the antibodies generated by these recovered patients’ immune systems will protect them from reinfection, at least for a while.

And if those same antibodies can be harvested from their blood and repackaged safely for administration to others, they may do something more remarkable.

In patients afflicted with COVID-19, they could boost the immune system’s response to infection, making their illness shorter and less severe.

When transferred to people who are not yet infected, those antibodies could act like a vaccine, teaching a recipient’s immune system how to recognize and fight the SARS-CoV-19 virus.

In short, as this pandemic spreads across the globe, convalescent serum has the potential to save lives.

“This is not a proven treatment,” U.S. Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Stephen Hahn cautioned at a White House briefing on Thursday. But he called it “a pretty exciting area” and described an effort crossing many federal agencies to explore it.

Chinese scientists also have acknowledged using the blood of recovered individuals as a potential treatment for COVID-19 infection.

With a U.S. vaccine as much as 18 months off and effective treatments still unidentified, some scientists believe that convalescent plasma could provide a bridge to safety.

They acknowledge that issues of safety, effectiveness and practicality still must be resolved. But they emphasize that this approach to both treatment and prevention could be fielded quickly and cheaply. They add that its risks can be minimized by the same rules and system that currently keep the U.S. blood supply among the safest in the world.

“We’re working feverishly” to explore the potential of convalescent plasma for COVID-19, said Dr. Arturo Casadevall, an immunologist and public health expert at Johns Hopkins University. “This is the only option for this country.”

In recent days, Casadevall and Dr. Liise-anne Pirofski, an infectious disease specialist at Albert Einstein School of Medicine, have been organizing a far-flung group of experts to design a medication based on convalescent plasma and conduct clinical trials to test its safety and effectiveness. More than 20 research institutions are involved in the effort.

Casadevall said he hoped to meet with officials from the FDA to obtain approval for three clinical trials of convalescent blood, and to gain the federal government’s support for the effort.

Working with blood bank officials in New York, the researchers hope to collect the blood of U.S. residents who either had confirmed infections from which they’ve recovered, or who believe they have weathered an infection.

“It’s not a new idea, it’s a very old idea,” said UC Irvine virologist Michael J. Buchmeier, who has studied the use of convalescent plasma for decades.

Creating a vaccine capable of preventing the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 will take many months — if not a year or more. These are the steps involved.

In an age where genetically engineered antibodies are the new norm, convalescent plasma seems quaint. And for drug companies that require a profitable market to justify the design and production of a new vaccine it is a distinctly unprofitable approach, he said.

“But the fact is, there is no reason that, if properly selected and screened, it can’t work,” he said. The only question, he added, is whether the current crisis is urgent enough to return to a tried-and-true approach that has gone out of favor.

In the early 20th century, convalescent plasma was used during outbreaks of polio, measles, mumps and flu, including the devastating 1918 influenza pandemic. Then, the process was often as primitive as putting two patients — one sick and the other recovered — on a pair of adjoining gurneys and running a blood transfusion line between them.

Today, the process would be far less simple.

First, researchers would have to discern when recovered patients’ COVID-19 antibody levels peak, and how long it takes for them to completely clear the virus. Both require the use of tests that are used only in research labs today, a practical hurdle that would require FDA action. Next, they’d separate and extract so-called neutralizing antibodies from the donated blood. Then lab workers would aggregate those antibodies into large batches and purify the resulting serum.

On average, Casadevall said, the neutralizing antibodies harvested from one robustly recovered individual might treat, or induce immunity in, as many as two others. The therapy could be made in batches that would combine the plasma of as many as 1,000 recovered patients, producing many doses at once

Before it could be used, however, its safety and effectiveness would need to be rigorously tested.

In addition to the risk of transmitting unrelated viruses to recipients, the same concern raised by vaccines that use live attenuated virus pertain: that some people will develop COVID-19 infection.

A further concern is that recipients who are already sick might develop powerful immune system reactions that could cause further damage, or even death.

Johns Hopkins has already approved the broad outlines of a clinical trial of convalescent plasma therapy as a means to protect healthcare workers, Casadevall said. These are people who will be continuously exposed to the new coronavirus and need immediate help, he said.

Scientists also hope to test the therapy in newly infected patients who have begun to develop worrisome symptoms but do not yet need a ventilator. If that proves successful, it could be tested on critically ill patients, Casadevall said.

With luck, “we may have data by the end of June,” said Casadevall, who with Pirofski recently made the case for convalescent plasma in the Journal of Clinical Therapy.

Such a therapy could not provide long-term immunity, he cautioned. But it could at least give healthcare workers a measure of protection until a vaccine is ready for broad use, he said.

Why does the coronavirus prompt dire warnings from the CDC about quarantines, school closures and other disruptions when we face flu season each year?

The use of recovered patients to help the sick and not-yet-infected is widespread in modern medicine.

Anyone who’s been bitten by a rabid animal, received a bone marrow transplant or given birth to a child has probably received a form of convalescent serum. They’re used to boost the immune response to rabies infection, to protect cancer patients from acquiring the herpes virus during a bone-marrow transplant, and to protect babies from contracting cytomegalovirus from their mothers during childbirth.

Convalescent plasma was widely used during the three-year West African Ebola epidemic that ended in 2016, though its effectiveness was not rigorously studied. More recently, it has been used to treat people with Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS.

As protection against the coronavirus that causes MERS, neutralizing antibodies extracted from macaque monkeys that had recovered from the disease were able to protect healthy macaques and prevent them from becoming sick when infected, said Dr. Stanley Perlman, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Iowa.

There are many details to be worked out, said Perlman, who studies coronaviruses and their treatments. But convalescent plasma has a bird-in-the-hand quality that is just too good to pass up, he said.

“I think it’s worth a shot to see what happens.”