True number of U.S. coronavirus cases is far above official tally, scientists say

An analysis of the novel coronavirus’ spread inside the United States suggests that thousands of Americans are already infected, dimming the prospects for stomping out the outbreak in its earliest stages.

Researchers estimate that by March 1, the virus had already infected about 1,000 to 10,000 people who have not yet been accounted for. At the start of this month, about 80 U.S. cases had been confirmed and officials were still expressing confidence they could contain the new virus.

Quarantines, contact tracing and other public health measures have likely tamped down the COVID-19 outbreak here, the researchers said. But from the start, a group of infected travelers just big enough to fill an elevator likely has been expanding the virus’ reach, largely undetected.

Released into a country of about 330 million, each of these travelers was assumed to have passed the virus to 2 to 2.5 people, each of whom in turn infected another 2 to 2.5 people, and so on. Tote up the nodes on this rapidly branching network of contacts and the number of victims balloons quickly, the researchers wrote.

Their study, released Monday on the medRxiv website to discuss work that has not yet been submitted to a peer-reviewed journal, came as U.S. officials reported a total of 704 COVID-19 cases and 29 deaths in the United States. That is likely just the tip of a much larger iceberg, the mathematical modeling suggests.

Under their most optimistic assumptions, as few as 1,043 people in the United States have been infected with the novel coronavirus. Under a more realistic scenario, that number could easily be as high as 9,484.

That only accounts for U.S. residents whose infections originated with people carrying the virus directly from Wuhan, the epicenter of the outbreak in China. In reality, many more people likely have brought the virus here from other hot spots, including Italy, South Korea and the rest of Asia. Each virus carrier who arrived from those places would set off his or her own cascade of infections.

The model also stopped adding up infections as of March 1. But given its firm toehold in the United States by then, the virus could have racked up tens of thousands of new cases since that date.

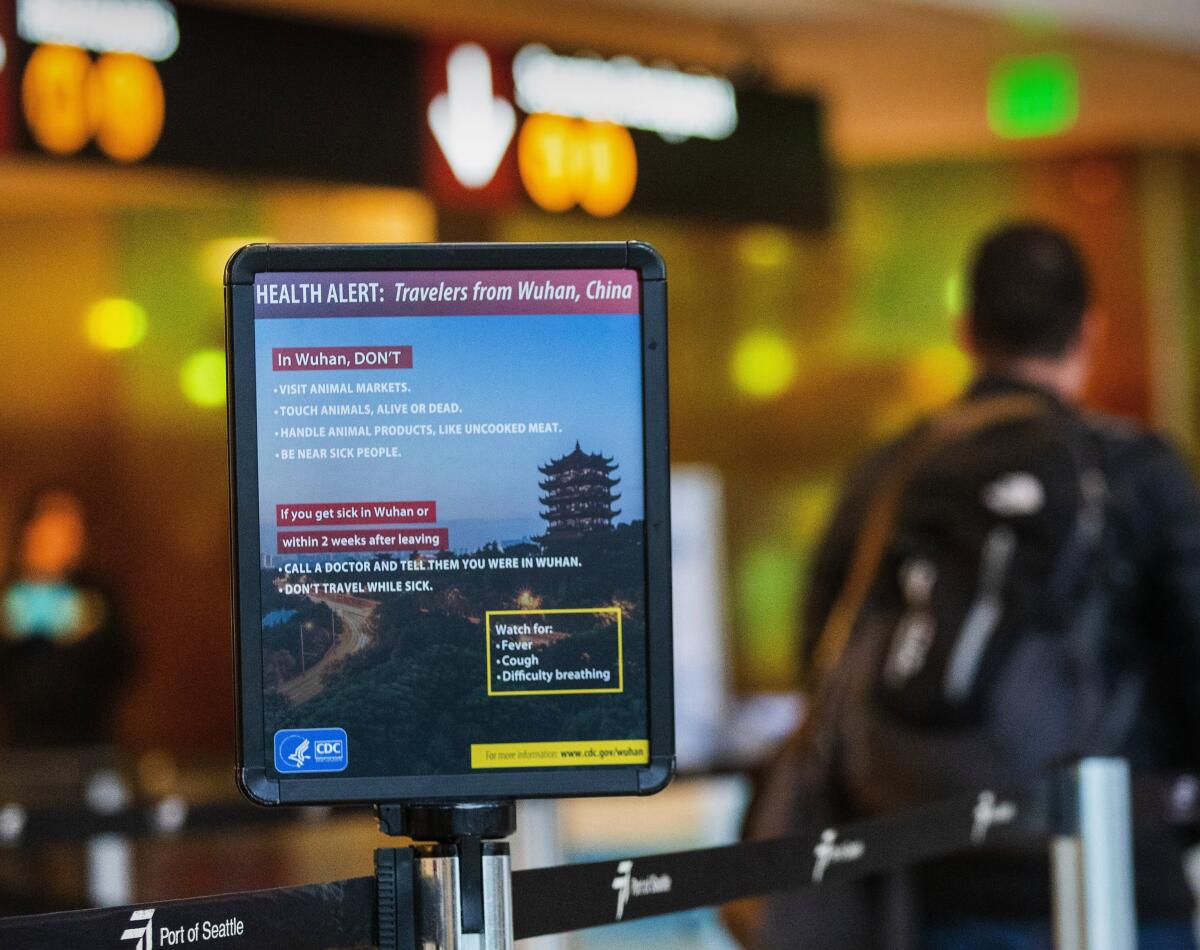

The mathematical simulation of the U.S. outbreak was run over a thousand times by a team from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and Peking University in Beijing. They began with a hypothetical group of undetected carriers — likely eight to 16 people — who arrived in the United States on direct flights from Wuhan after the virus now known as SARS-CoV-2 began infecting humans in late November but before those flights were halted on January.

It’s safe to assume that roughly half of these travelers were intercepted by U.S. health officials and saw their movements curtailed. The rest continued on their journeys with their undetected infections, each setting off an unrecognized chain of transmission.

While it is impossible to see, the scope of that transmission can be estimated by adopting a range of assumptions about the movements of infected people and the behavior of the virus.

Some of the team’s assumptions are grounded in data collected by Chinese epidemiologists who have tracked the virus as it has roared through China.

But other assumptions were a matter of judgment. Those included, for instance, the number of virus-exposed travelers leaving Wuhan in early January on U.S.-bound jumbo jets, and the impact of social isolation measures in limiting a person’s opportunities to spread the virus.

The fatality rate for the new coronavirus keeps changing. For weeks it remained at around 2%, then it seemed to drop to 1% before climbing above 3%. What gives?

Where they had a range of assumptions to choose from, the researchers said they deliberately rejected the most alarming suspicions about, say, the virus’ ability to jump from person to person. Instead, they consistently adopted measures of viral or human behavior that were more reassuring.

As a result, their estimate likely sets a lower boundary on the virus’ presence in the United States, the team wrote.

The analysis began circulating Monday among epidemiologists but has not yet been subject to the rigorous academic scrutiny that typically precedes publication in a scientific journal. The authors said they planned to post the assumptions, equations and computer code that drove their analysis so that other disease modelers could comment and expand upon their findings.

Experts in disease modeling said the preliminary model was a good start.

While it worked around many of the outbreak’s complexities, it has made reasonable assumptions and used plausible techniques that help describe the extent of the nation’s public health challenge, said Gerardo Chowell, a mathematical epidemiologist at Georgia State University.

“It’s good to keep things simple,” said Chowell, who studies the dynamics of epidemics.

Some of the researchers’ assumptions may overestimate the extent of undetected infection: in a country as large and diverse as the United States, many infected people may have gone home to low-density hometowns, where their chain of transmission fizzled, he said.

But other assumptions, including the researchers’ focus only on early travelers from Wuhan, have certainly underestimated the numbers of U.S. residents infected.

Dr. Donald S. Burke, a disease modeler at the University of Pittsburgh, added that the team’s assumptions about the coronavirus’ ability to jump from person to person is especially conservative.

The new analysis assumed that each infected person will pass the virus along to 2.1 to 2.5 others over the course of their infection, a number epidemiologists call the reproductive rate. But estimates of the coronavirus’ reproductive rate in circumstances where it is spreading undetected has ranged between 5 and 6, so the researchers may have greatly underestimated the number of infections in the United States, Burke said.

“The overall conclusion is, it’s very likely there’s a significant burden of disease we have yet to uncover,” Chowell said.

Some of that will likely show up as testing for the disease becomes more commonplace, he said. But much of the outbreak’s unseen underside may never be counted.