New drug overdose data capture earliest days of fentanyl’s deadly westward expansion

A rigorous effort to track U.S. overdose deaths and the drugs that caused them offers a snapshot of a fentanyl epidemic on the cusp of a westward shift.

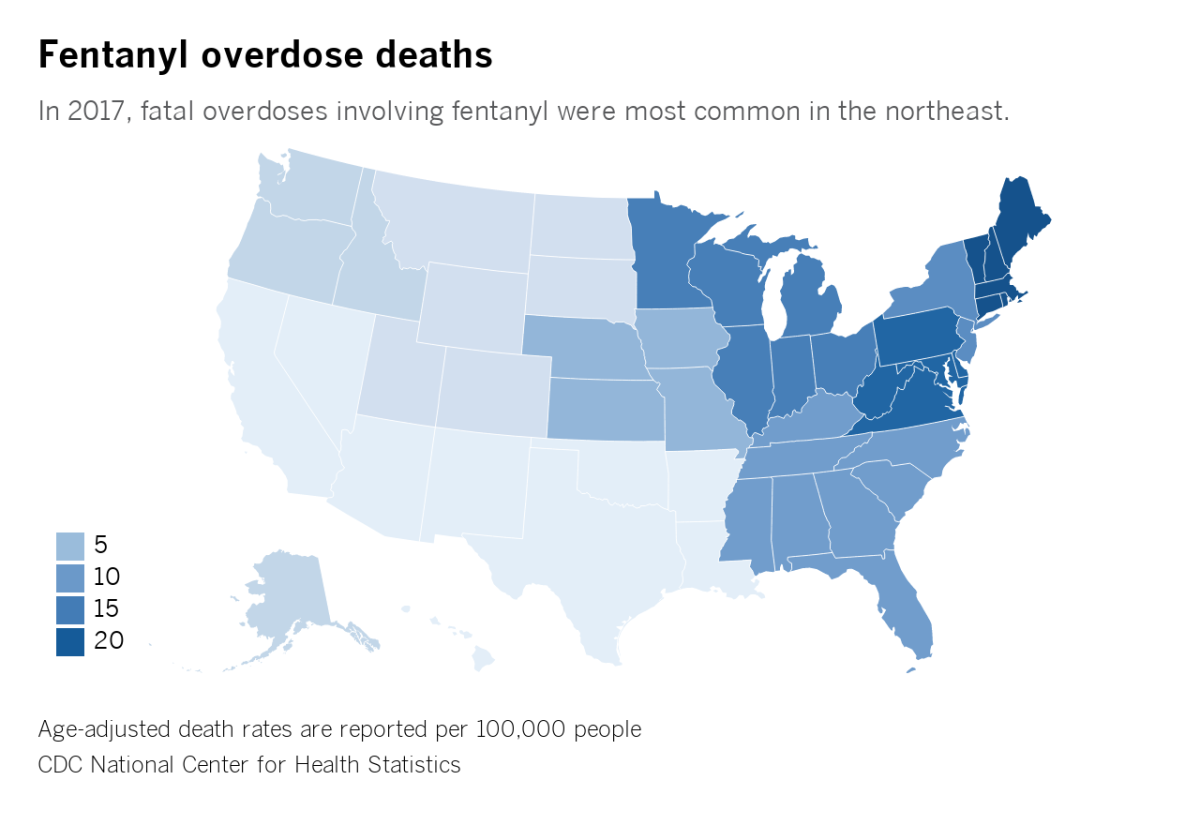

A study released Friday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows the synthetic opioid cutting a swath of death and destruction across the northeastern United States and the industrialized Midwest in 2017. That year, fentanyl was the drug cited most often as a cause of fatal overdoses in all five regions lying east of the Mississippi River, as well as the neighboring region that includes Iowa, Missouri, Kansas and Nebraska.

The picture was starkly different in the nation’s western states, where fentanyl barely registered as a cause of death. Instead, methamphetamine was the drug most often linked to overdose deaths in 2017.

Nationwide, fentanyl played a role in nearly 4 out of 10 fatal overdoses in 2017, more than any other drug. For every 100,000 Americans, there were 8.7 fentanyl-related deaths that year, according to the study from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics.

The U.S. opioid crisis has passed a dubious milestone: Overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids like illicit fentanyl have surpassed deaths involving prescription opioids.

Fentanyl, a drug at least 10 times more powerful than morphine, is “phenomenally inexpensive per dose,” according to a recent Rand Corp. report on the future of synthetic opioids. Widely used by cartels and drug dealers to boost the potency of other drugs of abuse, it was cited as a cause of death — sometimes alone but frequently in combination with other drugs — in 27,299 fatal overdoses across the country in 2017.

Those fentanyl-involved deaths were densely concentrated in the nation’s northeastern, mid-Atlantic and upper midwestern states. Only 1,769 overdoses linked to fentanyl — fewer than 7% of the national total — were recorded in the regions that include Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, Wyoming, the Dakotas and all of the states stretching westward from there.

Illicit fentanyl is thought to have penetrated the U.S. drug supply earliest and hardest in New England. In 2017, that region had a fentanyl overdose death rate of 22.5 per 100,000 — about 15 times higher than the prevailing rate throughout the western United States.

That picture has already begun to change, experts said. In 2018 and the opening months of 2019, evidence of fentanyl’s westward diffusion began to build.

Fentanyl “was rare for a minute on the West Coast,” said Dr. Daniel Ciccarone, a physician and medical anthropologist at UC San Francisco who studies trends in illicit drug use. “That’s not true anymore. We are in the killing fields now.”

As the scourge of fentanyl tightens its grip on western states, it could usher in a new chapter of the opioid epidemic, he warned.

“The opioid epidemic is maturing,” Ciccarone said.

The current public health crisis can be traced to the 1990s, when doctors began overprescribing opioid narcotics with encouragement from the drugs’ manufacturers.

By 2010, access to prescription pills was squeezed as doctors wrote fewer prescriptions, abuse-resistant formulations reached pharmacies, and efforts to prevent the diversion of pain medication to the black market were stepped up. Those addicted to opiates responded with a surge in heroin use, triggering the epidemic’s second wave.

Then in 2013, cheap and deadly fentanyl began reaching American shores from Chinese labs, launching a third wave of the opioid epidemic. A fourth wave could see fentanyl’s uptake spread across the country, fueled in part by its broader use in spiking drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine, Ciccarone said.

The synthetic opioid, which can cause death in a non-opioid user at doses as low as 2 milligrams, has already been seen in a variety of illicit drugs in the West. In addition to being cut into cocaine and methamphetamine, it is being pressed into counterfeit pills that look like exact replicas of prescription narcotic and anti-anxiety medications. Eventually, fentanyl is expected to find its way into heroin across the West.

Americans have long construed drugs of abuse as choices.

The new study, which used death certificates to glean geographic patterns of drug use, found that methamphetamine was cited as a factor in 5,241 fatal overdoses across the West in 2017. Heroin was generally the second-most-frequently cited drug on death certificates there.

Why fentanyl was slow to reach the western states is a topic of both debate and research..

Experts suggest that geographic differences in the customs of drug suppliers and users may account for the regional disparity seen in 2017. Illicit fentanyl is largely used by drug distributors to stretch the volume or boost the potency of other drugs, most notably heroin. That appears to be relatively easy with the white-powder form of heroin that circulates throughout the eastern United States and Midwest.

But cartels operating across the western states tend to sell heroin in a form that resembles sticky black or brown tar, which is less amenable to the addition of fentanyl.

“We don’t exactly understand why powder doesn’t go out west,” said Bryce Pardo, a Rand Corp. expert on the illicit drug trade. But the fact that it has not may have protected the region, at least temporarily, from fentanyl’s deadly grip, he added.

That barrier may be coming down.

In January, California emergency room doctors and county health officials documented a rash of apparent fentanyl overdoses. In Fresno, Chico and Madera Counties — all linked by Highway 99 — three died and 16 were treated and released after snorting what they thought was cocaine.

Fentanyl is also appearing in the form of counterfeit pills sold as the prescription painkillers oxycodone and hydrocodone, as well as the anti-anxiety drug Xanax. And last year, investigators at the Food and Drug Administration dismantled a network of counterfeiters in Northern California that was turning out fake Xanax and Percocet pills with Chinese chemicals and equipment.

Meanwhile, the Drug Enforcement Agency’s Phoenix Division reported in August that it had seized more than 1.13 million illicitly manufactured fentanyl pills between October 2017 and September 2018. That was up from 380,000 such pills the previous year.

Who is to blame for the nation’s deadly opioid epidemic? That’s the question at the heart of MDL 2804, largest civil action in U.S. history.

Finally, drug users’ behaviors have changed in ways that create a potential opening for fentanyl in the West. In parts of the East and Midwest, a practice called “goofballing” or “speedballing” — in which drug abusers mix heroin with stimulants such as methamphetamine or cocaine — has become a popular way to achieve a more intense high.

The trend has reached the West Coast. In June 2017, experts described an upsurge in heroin use among meth users in Washington’s King County.

“If it’s happening in Seattle, it’s happening here in San Francisco,” Ciccarone said.

As drug distributors cut fentanyl into all the drugs that make up a goofballer’s cocktail, deadly overdoses could increase. For people who do not typically use opioid drugs and have not developed a tolerance for them, the result of a double fentanyl exposure could be a rapid death.

A database of drug death in California suggests that fentanyl’s increased presence is already being felt in the state. In 2018, fatal opioid overdoses linked to fentanyl grew to 743 from 429 in 2017, representing close to a third of the state’s 2,311 opioid-related deaths.

“Fentanyl is still taking off — we haven’t seen that cycle peak yet,” Ciccarone said. But if current trends continue, he said, the outcome could be “horrible.”

It’s a dire warning echoed by a Rand Corp. report.

“Once fentanyl gains a foothold, it appears capable of sweeping through a market in a few years,” Pardo and his team of Rand researchers concluded. “The U.S. synthetic opioid problem is not yet truly national in scope. Some regions west of the Mississippi have been less affected to date. Those areas should be seen as at high risk of a worsening problem.”