In South El Monte, a small machine shop is a big part of Space Launch System

Mankind’s path to Mars winds through a small machine shop in South El Monte.

It is there, in the unassuming shops of AMRO Fabricating Corp., that NASA is getting the walls built for its powerful new heavy-lift rocket, called Space Launch System, that’s set to blast beyond low-Earth orbit within a few years to explore deep space and send humans to an asteroid and, ultimately, the Red Planet.

The three-generation family-owned metal fabricating business is making the enormous aluminum panels that will constitute much of the rocket’s body, as well as major parts of the Orion crew capsule astronauts will ride in.

AMRO sits on a quiet industrial stretch of Adelia Avenue, where men walk down the street in hard hats and coveralls. On an employee’s car parked outside AMRO recently, a bumper sticker proclaimed: #MarsOrBust.

“We’re building history,” said Aquilina Hutton, the president of the company. It’s just that most people, she said, don’t know it.

AMRO Fabricating Corp. in South El Monte is responsible for the rockets that will send NASA’s next manned mission to Mars. The three-generation family-owned metal fabricating business sits on a quiet industrial stretch of Adelia Avenue. “We’re build

A working-class city of just over 20,000 people, South El Monte is sometimes mistaken for its much larger neighbor El Monte, population about 116,000, which calls itself “The End of the Santa Fe Trail” — but not the beginning of an interplanetary journey.

Aerospace once was a bright spot in the Southern California economy. NASA’s decades-long space shuttle program underpinned the industry in the region, providing jobs for everyone from Ivy League-educated engineers to blue-collar machinists, and giving work to scores of mom-and-pop businesses like AMRO that supplied the parts.

But in recent years, aerospace giants such as Boeing and Lockheed Martin have slashed thousands of jobs and closed facilities across the region. And the space shuttle program that created so much work is now over.

AMRO, which used to build pieces of the shuttles’ huge external tanks, eliminated jobs after the program ended. But now, working on a Boeing subcontract, the little company is humming with work on the Space Launch System, or SLS.

“Our country doesn’t know that we’re building a new rocket,” said Steven Riley, AMRO’s vice president and Hutton’s brother. “They think that once the space shuttle was done, we were done.”

The first, and smallest, version of Space Launch System will stand 322 feet tall and produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust at liftoff — the equivalent of more than 160,000 Corvette engines, according to NASA. Its first fly test, carrying an unmanned Orion crew vehicle, is slated for 2018. NASA aims to send humans to Mars in the 2030s.

Work on the mega-rocket is spread throughout the country. In California alone, more than 700 suppliers and subcontractors are working on the Orion and Space Launch System, said Kimberly Henry, a NASA spokeswoman.

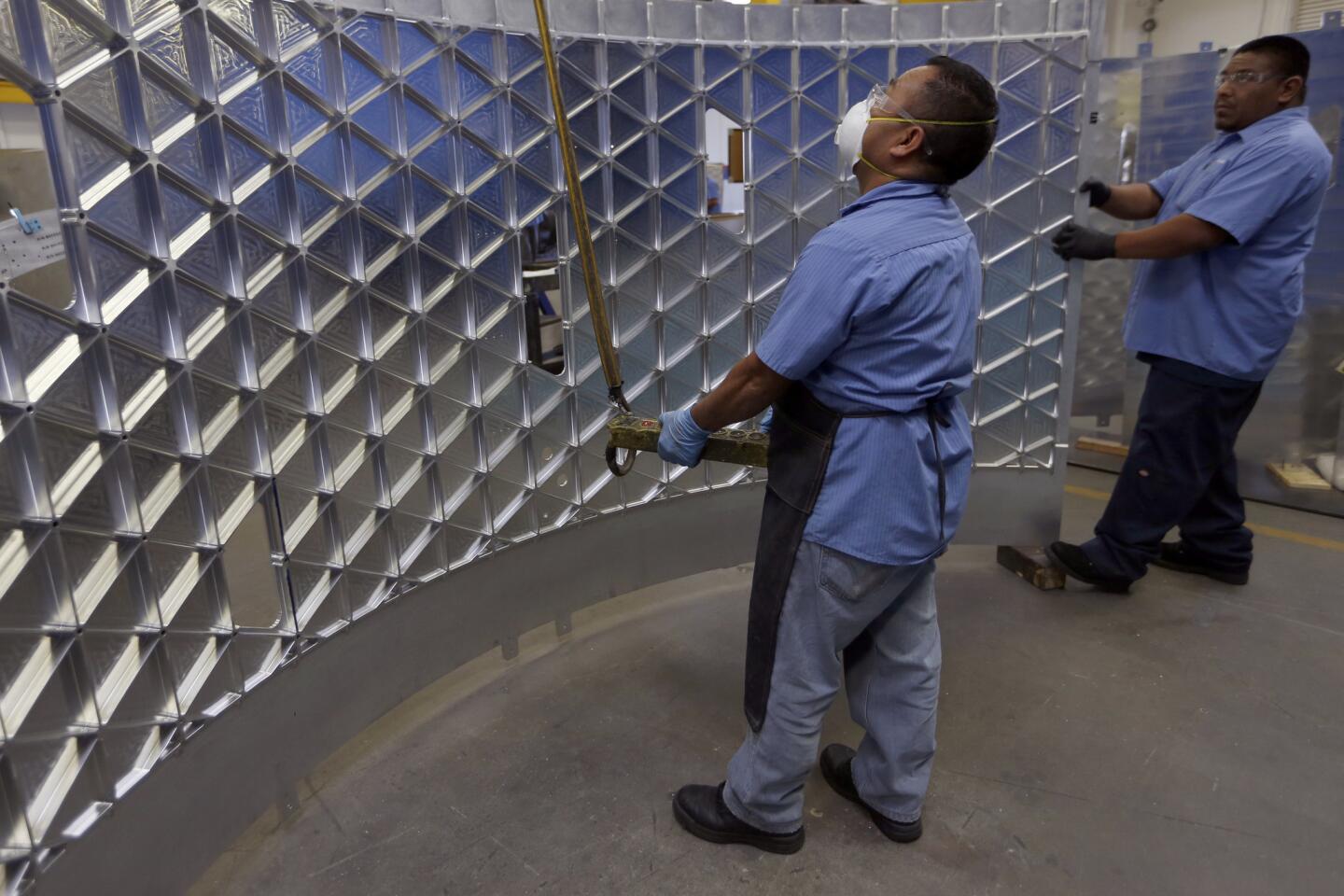

At AMRO, machinists are making the intricate curved aluminum panels that form the walls of the rocket’s core stage — the main body that carries fuel, holds the twin solid rocket boosters and has engines affixed to its bottom. After liftoff, the core stage detaches and burns up in the atmosphere.

When finished, the panels are shipped to NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans, where the rocket will be put together.

“AMRO is probably making more primary structure on the Orion-SLS combined rocket than anybody else,” said Steve Doering, who oversees the building of the core stage for NASA.

For Michael Riley, the company’s 81-year-old founder, the story of AMRO is the story of his life. He fell in love with a pretty little lady, they opened a shop, and their kids and grandkids helped grow it into a NASA darling.

“It’s the American dream,” he said. “Two kids got married at 19 and started a business, and now we’re going to Mars.”

It’s the American dream. Two kids got married at 19 and started a business, and now we’re going to Mars.

— AMRO Fabricating Corp. founder Michael Riley, 81

As a teenager in the early 1950s, Riley worked as a service boy at a gas station frequented by a young lumber company bookkeeper named Thora. Pretty soon, they started dating.

He was a Catholic whose mother wanted him to become a priest. She was a Mormon who’d grown up in church.

“Both sets of parents just knew that it was doomed for failure from the get-go,” Riley said, holding his wife’s hand. “But we knew better.”

So they ran off to Reno and eloped. Their families learned about the marriage when, unbeknownst to Michael and Thora, it was listed in the Sacramento Bee. They’d raise their kids as what one son called “Cat-Mor,” going to the Catholic church one week, the Mormon church the next.

In the mid-1950s, Michael started working in an Aerojet plant in Rancho Cordova, mixing thick, dough-like solid rocket propellant for the Navy’s submarine-launched Polaris missile.

“At that point, there was no space concept,” Riley said. “We were in the Cold War. Their primary target was Russia.”

The Rileys moved to Southern California in the 1960s. Michael took an engineering job, building submarine parts, and eventually managed a metal fabricating division.

With their kids in college, Michael and Thora decided to open their own metal fabricating shop. They figured the business should start with an “A” so it would appear at the top of the phone book. They settled on AMRO — A Michael Riley Operation.

In 1977, AMRO opened an 8,000-square-foot shop in South El Monte with six employees. One of their biggest jobs was making metal frames that held HEPA filters.

Under the leadership of their daughter and son, Hutton and Steven Riley, AMRO for years made the panels that made up the space shuttles’ super-lightweight external tanks.

When the shuttle program ended, they were told to destroy all the remaining panels, and major parts of their shop were empty and quiet, said Michael E. Riley, AMRO’s 31-year-old director of space flight hardware and Steven’s son. When the retired shuttle Endeavour flew overhead atop a Boeing 747 aircraft in 2012 en route to its new home at the California Science Center, AMRO workers watched sadly in the parking lot with a truckload of cut-up tank panels sitting nearby.

Space Launch System, Riley said, was a godsend. In the AMRO shops on a recent day, curled aluminum shavings from the machines covered the floor like glimmering sawdust.

The panels start as flat aluminum plates weighing about 10,000 pounds. Using milling machines, workers carve out pockets in intricate Isogrid designs, reducing the plate to about 1,000 pounds, he said. Every pound matters in space, so the goal is to make the plates as light as possible while still being strong. Each is ultrasonically checked for impurities and cracks.

“There’s no room for error,” he said.

Workers use laser trackers to show the exact spot of each Isogrid rib, which can’t be off by even as much as the width of a piece of paper, Riley said. The panels are curved in an enormous press brake that applies around 1,000 tons of force, Riley said.

Andres Martinez, a press brake operator who’s been with AMRO for 30 years, said he was proud of his work.

“It takes a lot of patience,” he said. “Every piece is different.”

Every once in a while, an astronaut walks through the shop, shaking the machinists’ hands, telling them they’re important.

“For the guys that are on a mill or on a press brake, it’s no longer just a piece of aluminum that they’re building,” Steven Riley said. “If you mess up your part, astronauts are going to lose their lives.”

Twitter: @haileybranson

ALSO

California’s use of coal drops dramatically — to almost nothing

The Coastal Commission hopes to restore public trust with its latest decision

How tech mogul Larry Ellison’s friendship with a USC doctor led to $200-million cancer research gift