Q&A: A former NASA astronaut says it wouldn’t be so bad to transfer the space station to private management

When word got out that the Trump administration wanted to end government funding of the International Space Station by 2025, resistance to the idea was swift and forceful.

In a rare sign of just how unpopular it was, two senators from opposing parties — Democrat Bill Nelson of Florida and Republican Ted Cruz of Texas — immediately came out against the proposal, which was contained in the president’s 2019 budget blueprint.

But former NASA astronaut Sandy Magnus said that stepping away from the space station could be seen as a sign of progress toward the eventual goal of sending humans out into the solar system. By transferring management of the ISS to private industry, she said, NASA still could lease space to continue its research in low Earth orbit while focusing more of its efforts on places like the moon and Mars.

“It’s a question of, does NASA own the building or is it leasing the building?” said Magnus, who lived on the space station for 4 1/2 months in 2008 and 2009.

It’s “neither a good or a bad thing. It is the next stage in the evolution,” she added. “But we’ve got to do it well.”

After leaving NASA, Magnus became executive director of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, a position she held until January. She spoke with the Los Angeles Times about the pros and cons of having NASA stop operating the space station.

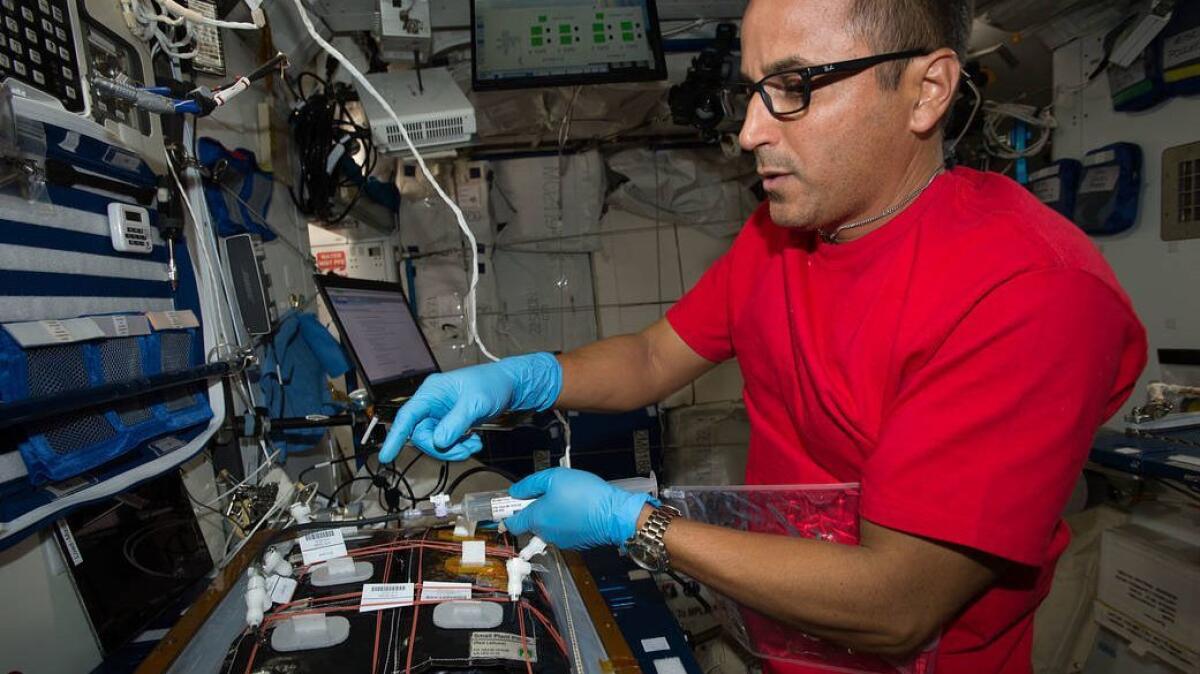

What type of research is happening on the International Space Station?

It’s everything from microbiology to biology to biochemistry to animal studies to human studies to material science to combustion science to Earth science and space science. Also, psychology and human behavior.

Why is it important to do this research in space?

There are a lot of things we learn in microgravity about how cells behave, about how human physiology changes, how materials can form, how fluids operate and how combustion processes work that we can’t learn about on Earth because gravity is such a horrible all-pervasive force.

It really is, trust me.

And it’s not just science, it’s engineering too?

Right. If we want to expand human spaceflight beyond low Earth orbit, we have to take all the global systems that work naturally on Earth and figure out how to design them mechanically to work on spacecraft.

If you are going out to the moon, or to Mars, or even farther someday, you need to have your own closed system for life support. That’s what we’re testing on the space station.

Would the White House’s proposal to stop directly funding the space station after 2024 hurt this type of research?

The question about the future of the Space Station is: How do we maintain a science research and technology development platform, but expand its capabilities so it is not just the government owning or 100% using that platform? In theory, the White House plan is not bad, but the execution is going to be critical.

Are private companies working with the space station now?

It’s happening in a few different capacities. In general the kind of companies that use the station for research and development are biology companies, microbiology companies and drug companies. In part that’s because these are systems that behave very differently in microgravity. Also, the experiments are easy to get up and down.

But we are still at the very beginning stage of developing a market of people who want to go to space if it’s not subsidized by the government. Who is going to go up there to do research? How can we make it so that it is not just the government leasing a building, but the government leasing a building that other people are also leasing too?

Do you know of any companies that are ready to take on management of the Space Station?

Even now, the Space Station is not operated just by NASA. There are other companies, like Boeing, that have contracts with NASA to help manage it. Two companies, Bigelow Aerospace and Axiom Space, are interested in attaching a commercial lab to the Space Station, but whether they are able to take over operational control of the whole thing, I don’t know.

What’s good about having private industry involved in the space station?

As more companies and people get into research and development in low Earth orbit, I think we’ll get more creative ideas both about the fundamental science we can do there and about what products we can create in space.

As a scientist and engineer, I understood how gravity played into my physics and engineering equations. But when you go to zero gravity and actually see how things behave differently, you understand it on a different level.

When we can get more people up there, that will be the tipping point for making people realize that, “Oh, I can do this experiment.” “Oh, I can develop this product.” Or, “I could research this line of inquiry that would help people on Earth.”

The U.S. has several international government partners who share management of the ISS. If NASA privatizes its part, what happens to them?

That’s a big question mark. These discussions have already started, and I think you’re going to see a lot of churn around this issue over the next six to nine months because nobody knows what it’s going to look like. This is a very interesting creative moment we’re in.

Does having a company run the space station rather than the government contaminate its mission?

Don’t look at it as private industry or government. You have to look at it as private industry and government.

If we get more people engaged in low Earth orbit so the government doesn’t have to spend as much time there, then the government can put its resources into going beyond low Earth orbit — like going back to the moon and eventually onto Mars, and maybe on to Europa 100 years from now.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and "like" Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

A rare signal from the early universe sends scientists clues about dark matter

When NRA members attend their convention, ER doctors see fewer patients with gun injuries, study says

How life on Earth might survive on Saturn's ice moon Enceladus