Scientists capture ‘mesmerizing’ video of swarming red crabs

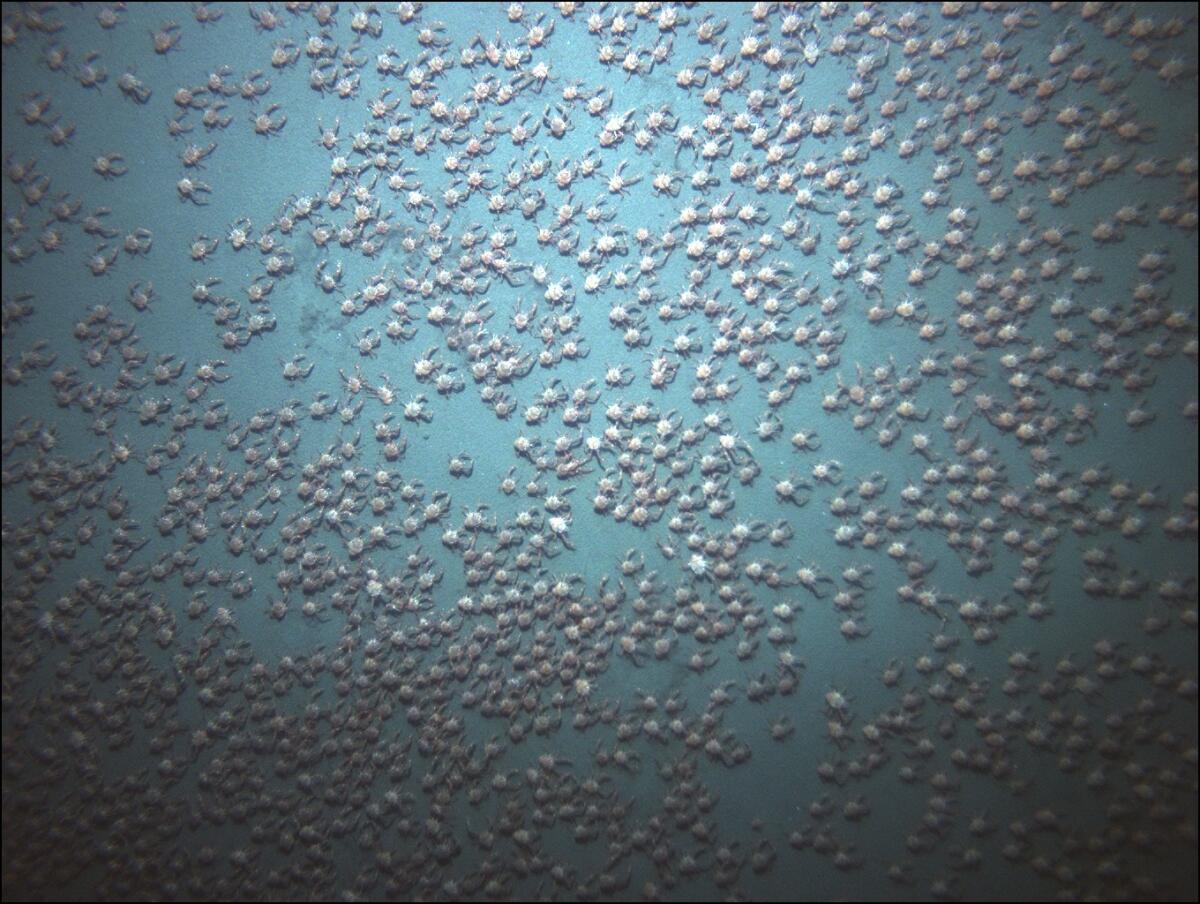

A swarm of red crabs kicks up a cloud of mud and sediment as it moves along the ocean floor of the Hannibal Seamount off Panama.

More than a thousand feet below the surface, the ocean floor seemed to come alive before the eyes – and cameras – of a team of scientists.

While studying biodiversity at the Hannibal Bank Seamount, an underwater mountain off the coast of Panama, the researchers spotted something unusual from their submarines.

“We saw a cloud, a really big cloud,” said Jesus Pineda, a biological oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts. “We were thinking, what in the world is this?”

What looked like rocky structures started to move and jump. Thousands of red crabs had amassed into a swarm and began scuttling along the seafloor, kicking up a 30-foot-high cloud of mud in their wake.

Pineda and fellow scientists captured the “mesmerizing” scene on video back in April 2015, describing their unexpected findings in a new study published in the journal PeerJ.

The swarm of red crabs photographed from a submarine.

The scientists had originally set out to study biodiversity around the seamount and what makes the underwater mountains such ecological hot spots. After the team spotted the swarm of crabs on their last diving mission of the monthlong survey, their focus changed.

The scientists used DNA samples to identify the species of crab as Pleuroncodes planipes, a species most common in the warmer waters off Baja California. While scientists aren’t sure how far south the species’ range goes, previous studies have drawn the line around Costa Rica. The sighting in Panama suggests a new record for how far south populations of P. planipes occur.

A few months after Pineda’s expedition, P. planipes was making headlines in California. In June 2015, thousands of the red crabs washed ashore in San Diego. Later that summer, they were filmed invading the Channel Islands.

Red crabs are also called squat lobsters and tuna crab for the yellowfin tuna that eat them. As juveniles, the crabs are pelagic, meaning they spend their time swimming and drifting in the water. But that makes them vulnerable to changing ocean currents, especially in El Niño conditions.

While it’s unlikely the Panamanian swarm is connected with the mass strandings in California, it’s unusual for a single species to occur so abundantly in two wildly different habitats, the authors wrote.

The scientists were also astonished by the sheer number of crabs they found at Hannibal Seamount.

Along the study route, the team counted three tightly packed groupings of red crabs. Measurements from an autonomous underwater vehicle showed the crab clusters were densest toward the center, with up to 78 individuals per square meter. This swarming structure has also been seen in insects, krill and schooling fish.

Pineda said P. planipes have never been seen in such high densities before, which means the species probably occurs even further south than Panama.

“We just haven’t found them yet,” he said.

The team still has unanswered questions about Hannibal Seamount and plans to return.

Seamounts attract a diverse array of ocean life, but scientists aren’t exactly sure why. According to one hypothesis, underwater mountains redirect ocean currents and nutrients closer to the surface, where there’s light. That allows phytoplankton and plants to grow, followed by all the larger fish and animals above them on the food chain.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

Follow me on Twitter @seangreene89 and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE SCIENCE NEWS

NASA Kepler spacecraft recovers from emergency mode, but what triggered it?

Chauvet cave: The most accurate timeline yet of who used the cave and when

What a 10,000-year-old massacre can tell us about the origins of human violence