How raw meat -- and our ancestors’ inability to chew it -- changed the course of human evolution

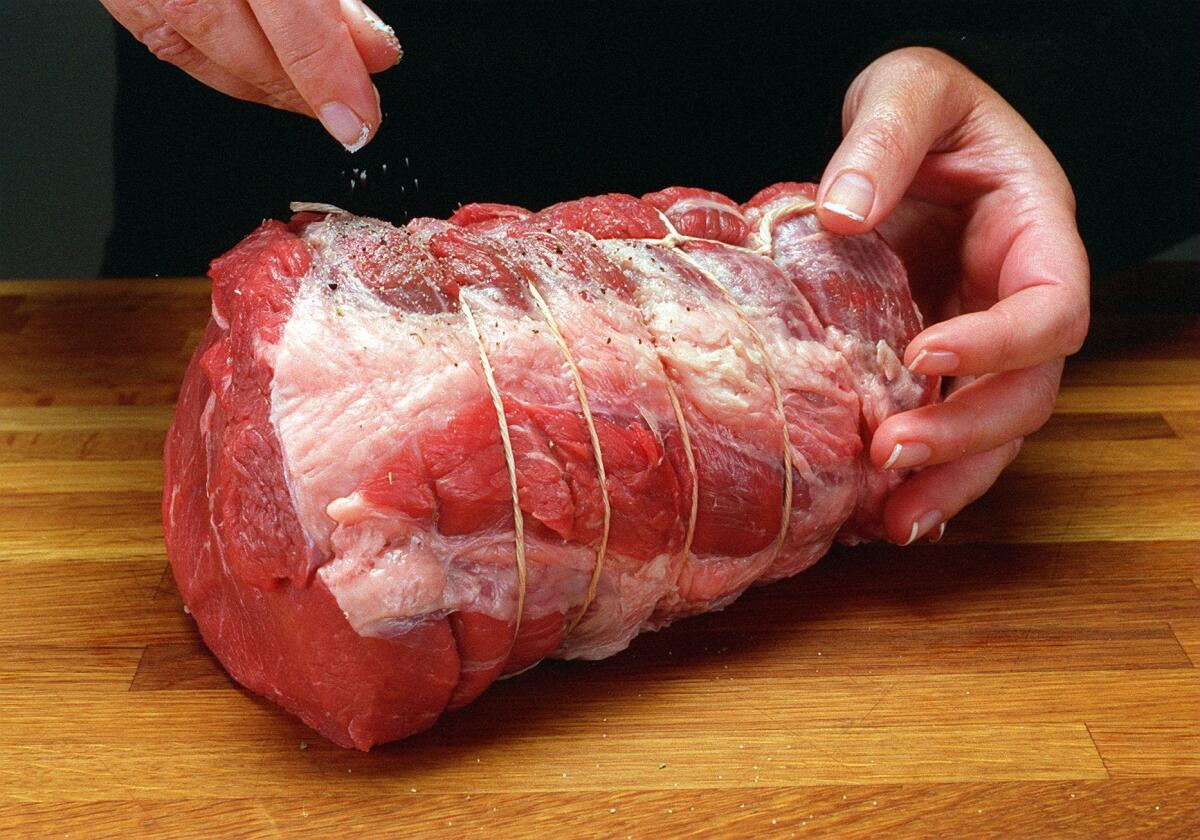

A new study suggests that neither we nor our ancestors were capable of eating raw meat without some form of processing.

Paleoanthropologist Daniel Lieberman chewed raw goat meat for the sake of science, so he knows from experience that it’s a challenge.

“It’s a little salty, and it’s very tough,” the Harvard University professor said. “You put it in your mouth and you chew and you chew and you chew and you chew, and nothing happens.”

As Lieberman discovered first hand, modern human teeth are not suited to breaking chunks of raw meat into pieces that are small enough to swallow.

Effective raw-meat eaters like wolves and lions have teeth that are designed for slicing through elastic muscle, almost like a pair of scissors. Humans, on the other hand, have teeth that act like a mortar and pestle. Our pearly whites are designed for crushing, not slicing. When we chew on raw meat, the meat does not break apart.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

“It stays like a wad in your mouth,” Lieberman said. “It’s almost like a piece of chewing gum.”

Still, the fossil record suggests that ancient human ancestors with teeth very similar to our own were regularly consuming meat 2.5 million years ago. That meat was presumably raw because they were eating it roughly 2 million years before cooking food was a common occurrence.

Yet oddly, these meat-eating hominims had smaller teeth compared to their mostly vegetarian predecessors, as well as reduced chewing muscles and a weakened bite force, anthropologists say.

“With the advent of our genus, we start to see this suite of changes that continue on throughout time,” said Katherine Zink, a human evolutionary biology researcher at Harvard. “In general, we see decline in tooth size and jaw size.”

It is a seemingly strange evolutionary choice. Why would our ancient ancestors have a reduced ability to chew just after their diet became more gamy? Keep in mind that around the same time, their brains got larger, and their foraging ranges increased, causing their energy needs to grow.

A study published Wednesday attempts to address this paradox.

Writing in the journal Nature, Zink and Lieberman propose that the rise of meat-eating in hominims was possible only after our ancestors began using stone tools to help them process their food.

After running a series of tests in the lab, the authors report that hominims eating a diet composed of one-third meat and two-thirds root vegetables like beets and carrots, would see a 17% reduction in the number of chews required to ingest their food if the meat was first sliced with a sharp stone tool, and the root vegetables were pounded with a rock.

That equates to 2.5 million fewer chews per year, Zink said.

To come to this conclusion, Zink recruited more than a dozen chewers — most of them colleagues in the Human Evolutionary Biology department at Harvard. (Lieberman offered himself up as an early guinea pig, although his personal chewing results were not included in the paper).

Eight electrodes were attached to each volunteer’s face to measure the activity of four distinct chewing muscles — one on either side of the jaw bone, and one at each temple. An electrode also was attached to each participant’s hand to filter out background activity.

In addition, the chewers were outfitted with a dime-size force transducer that was placed between the first left molars. This allowed the researchers to measure chewing force.

The subjects then were given different samples of meat and raw vegetables to chew. Some of the samples were completely unprocessed, while others were sliced or pounded with a stone tool before being handed over. Still others were roasted.

Raw goat meat was used in the tests because it was the closest approximation of wild game that Zink could find. She said that it was frozen and then tested for pathogens before being thawed and fed to participants.

Volunteers were asked to chew each sample until they would typically swallow their food — usually about one minute or 20 to 40 chews. At that point, they spit their food out so that the particle sizes could be measured.

Researchers found that humans are simply not able to consume meat without some sort of processing, but that the rudimentary slicing of meat allowed it to be broken down into small enough pieces to be swallowed.

They also found that cooked meat requires more force to chew than raw meat, but because the fibers are stiffer, it can be broken down between the teeth.

Based on this evidence, the researchers argue that simple mechanical processing would have been required for our ancestors to make meat a regular part of their diets. They also say that the ability to process this meat allowed for the selection of smaller jaws and teeth that is evident in the fossil record.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

“We didn’t just start eating meat,” Lieberman said. “We had to invent some technology in order to be able to do it.”

Zink and Lieberman further reason that once the mechanical work of breaking down food could be started outside the oral cavity, it would have left our ancestors free to use their mouths for other things besides chewing — like talking.

“If you are using less force and using fewer chews, you are, of course spending less time eating,” Zink said. “And if you no longer need to maintain the big jaws and big teeth, it allows natural selection to choose for other performance benefits that improve fitness and survival.”

David Strait, a physical anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis who was not involved with the study said Zink and Lieberman are not the first to address how slicing or pounding food may have affected human evolution, but they are the first to use experiments to examine the issue.

“This means that previously we were speculating, but now we have actual data,” he said. “ And that is a good thing.”

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE SCIENCE NEWS

Doctors group calls on pediatricians to address child poverty

What’s wrong with the American diet? More than half our calories come from ‘ultra-processed’ foods

Stalking wildflowers in the Anza-Borrego desert to forecast the Big Bloom