Case closed: Oldest known cave art proves Neanderthals were just as sophisticated as humans

Scientists uncover cave art created by Neanderthals.

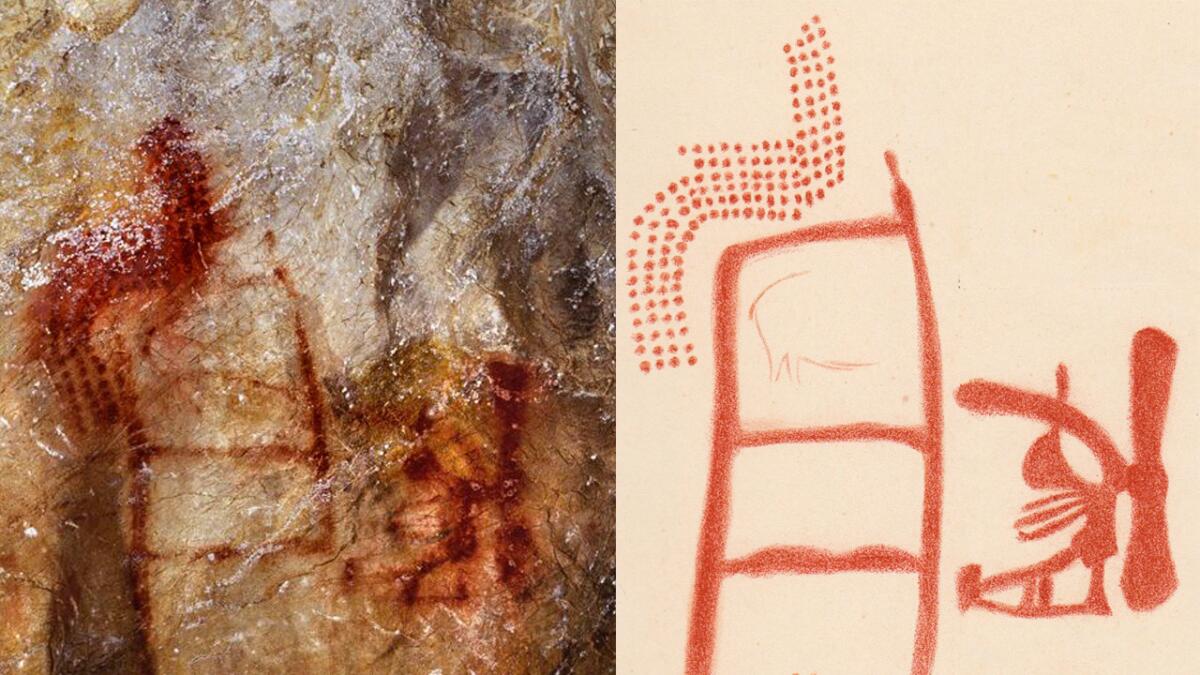

A red hand stencil. A series of lines that look like a ladder. A collection of red dots.

These images, painted in ocher on the walls of three separate caves in Spain, are the oldest-known examples of cave art ever found. And new research suggests that all three were created not by humans, but by our ancient cousins the Neanderthals.

In a paper published Thursday in Science, an international team of archaeologists shows that each of the three paintings was executed at least 64,000 years ago — more than 20,000 years before the first modern humans arrived in Europe.

“This work confirms that Neanderthals were indeed using cave walls for depicting drawings that had meaning for them,” said Marie Soressi, an archaeologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands who was not involved in the study. “It also means that our own group, the one we call anatomically modern humans, is maybe not so special.”

For most of the last century, researchers have argued that our Neanderthal cousins were intellectually inferior to their modern human contemporaries — incapable of symbolic thought and possibly devoid of language. This, in turn, was used to explain why the Neanderthals disappeared from Eurasia about 40,000 years ago, not long after modern humans arrived there.

However, archaeological evidence revealed over the last two decades tells a different story. We now know that Neanderthals were sophisticated hunters who knew how to control fire, and that they adorned themselves with jewelry and took care to bury their dead.

In addition, genetic evidence suggests that modern humans and Neanderthals were similar enough that they interbred with some frequency. Indeed, if you are of European or Asian descent, it is likely that roughly 2% of your genome comes from Neanderthal ancestors.

Still, Soressi said the discovery that at least three instances of known cave art were created by Neanderthals is significant.

“The one criteria left that would have distinguished Neanderthals and early modern humans was the interest and need to draw symbols deep in the underground,” she said.

Thanks to the new discovery, she added, we now know that Neanderthals and modern humans had that in common as well.

For this work, archaeologists traveled to three different cave sites across Spain: La Pasiega in the north, which is home to the mysterious ladder-shaped painting; Maltravieso in the west, where the hand stencil was found; and Ardales in the south, where red dots were painted on curtain formations inside the cave.

The three caves were discovered in 1911, 1951 and 1821, respectively. All of the artworks examined in the study had been known about for decades — although they were generally assumed to have been made by modern humans. Archaeologists have only recently gained access to tools that allowed them to accurately date the minimum age of the paintings.

Paul Pettitt, an archaeologist at Durham University in England who worked on the study, said the team targeted the three caves because each was known to contain symbolic, non-figurative art. Based on the team’s previous research, the authors guessed that these images, painted by hand in red ocher, would have been some of the earliest works in the caves.

These works of art took some planning to execute — requiring a light source, the preparation of pigments, and a decision about where to place the painting.

The hand stencil in particular is a relatively demanding piece to do, said Dirk Hoffman, the archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, who led the study. The artist placed his or her hand on the wall and then painted over it. When the hand was removed, its “negative” was left, imprinted on the cave.

To determine the age of the paintings, the researchers used a technique known as uranium-thorium dating that measures the age of calcitic crusts that form on the walls of caves. By calculating the age of crusts that formed over the paintings, the authors were able to discern minimum ages for the artworks.

The uranium-thorium dating technique requires a very small sample of the carbonate crust — about 10 milligrams. The researchers carefully scraped the crust off the paintings without damaging the art, then sent the samples to two labs for analysis.

The results indicated that the ladder shape was painted no later than 64,800 years ago, and the hand stencil goes back at least 66,700 years. The oldest of the red markings on the curtain formations dated back at least 65,500 years.

“Keep in mind, these are minimum ages,” Hoffman said. “We have no idea how much time elapsed at the three caves between the painting act and calcite precipitating on it.”

Even so, these findings show beyond a shadow of a doubt that the three paintings were created by Neanderthals, the researchers wrote, as there were no other hominids living on the Iberian Peninsula before roughly 40,000 years ago.

Matthew Pope, an archaeologist at the University College of London who was not involved in the work, said the new study won’t necessarily change how he and his colleagues think about Neanderthals. At this point, many of them have already concluded that our ancient relatives had gotten woefully short shrift in the past, he said.

But he added that the work “may remove one of the last elements that separate the behavior of Neanderthal populations from modern humans in the archaeological record.”

In other words, Neanderthals may have looked different than modern humans, but cognitively it appears they were just like us.

Soressi, the archaeologist from Leiden University, said one complication of these recent revelations is that it makes the demise of the Neanderthals harder to explain.

“All of what we know today tells us that it is not because Neanderthals were dummies that they disappeared,” she said.

As for what the paintings meant to their creators, Hoffman said we may never know.

However, he said the team of researchers is already at work dating paintings at other cave sites.

“It is certainly possible to find as old or even older cave art in other parts of Europe or even outside Europe,” he said. “We will see what future dating work tells us.”

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and "like" Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

An amateur astronomer testing a new camera happens to catch a supernova as it's being born

Instead of nagging your spouse to lose weight, try going on a diet yourself

Your DNA won't determine the best diet to help you lose weight

UPDATES:

2 p.m.: This story has been updated with additional information about the history of the artworks and comments from archaeologist Paul Pettitt of Durham University in England.

This story was originally published at 11 a.m.