Here’s what gives kingsnakes the edge in snake-to-snake combat

Here are eight facts about king snakes, according to LiveScience. (March 29, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

Nature draws a pretty clear distinction between predators and the things they eat: Predators are bigger than their prey.

Except no one told the kingsnake.

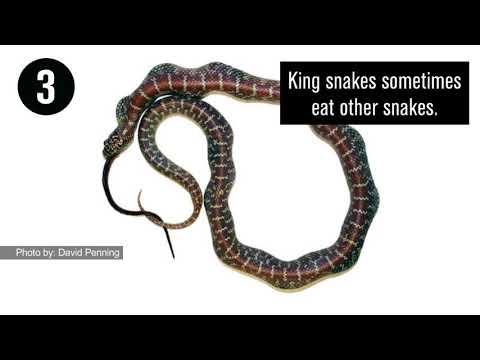

Kingsnakes squeeze their prey to death, are immune to rattlesnake venom and are so named for their astonishing ability to overpower and eat snakes that are much larger than they are.

“Pick an ecosystem, pick a food web, pick anything you know on the planet … and 90% of the time, predators are bigger than what they eat,” said David Penning, a biologist at Missouri Southern State University. “Then you meet the kingsnake, and they just defy that.”

What gives the kingsnake the edge in snake-to-snake combat?

To find out, Penning, then a doctoral student at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, and Brad Moon, his advisor and coauthor, devised a series of experiments for three species of kingsnakes and three species of rat snakes.

While rat snakes are generally larger, they always seem to wind up on the losing end of wrestling matches with kingsnakes. Once the rat snakes are vanquished, the kingsnakes have little trouble swallowing their foes whole.

On paper, however, the two snakes should be equal matches.

Similar sized kingsnakes and rat snakes have about the same number of muscles, which they can use to constrict something or escape constriction themselves, the researchers write.

The researchers measured the constriction strength of 182 snakes using dead mice wired with pressure sensors. (The researchers chose mice to make it a fair comparison, since rat snakes are not known to feed on other snakes.)

Kingsnakes emerged the clear winner. All three kingsnake species produced significantly higher constriction pressures than all three rat snake species. Some were so strong they could squeeze twice as hard as was necessary to kill a rodent.

The researchers also tested each species’ “escape performance,” or a snake’s ability to pull itself free from restraints.

To measure this, Penning and Moon used a piece of gaffer’s tape to secure the snakes to a surface as they pulled against a spring scale. Only the size of the snake — not the species — made a difference in their performance. This shows the kingsnakes are able to beat rat snakes because they are the superior constrictor — not because rat snakes aren’t able to escape.

“Kingsnakes were just pound for pound stronger than rat snakes,” Penning said.

Part of the kingsnakes’ success may be due to their coil posture. Both types of snakes constrict by winding their bodies one to three times around their prey.

Almost all the kingsnakes approached this in the same way, forming a neat spring-like pattern around their victims. But rat snake coils are sloppier, looking a little more like scaly pretzels knotted around their prey.

“It is possible that the kingsnake coil posture might maximize the force applied (and therefore pressure) to the prey,” the researchers wrote.

Penning and Moon published their findings this month in the Journal of Experimental Biology. (They had previously teamed up to measure the strike velocities of vipers and nonvenomous ratsnakes.)

Though the new results were surprisingly clear-cut, Penning said there’s more to learn about what makes kingsnakes the king.

Perhaps kingsnakes are simply more efficient or capable of contracting harder. Kingsnakes might also be able to endure longer bouts of constriction than their opponents, Penning said.

MORE IN SCIENCE

Defying man and nature, the sea otters of Morro Bay have made a comeback

Why would beetles want to look, act and smell like army ants? To eat them, of course