Study probes DNA search method that led to ‘Grim Sleeper’ suspect

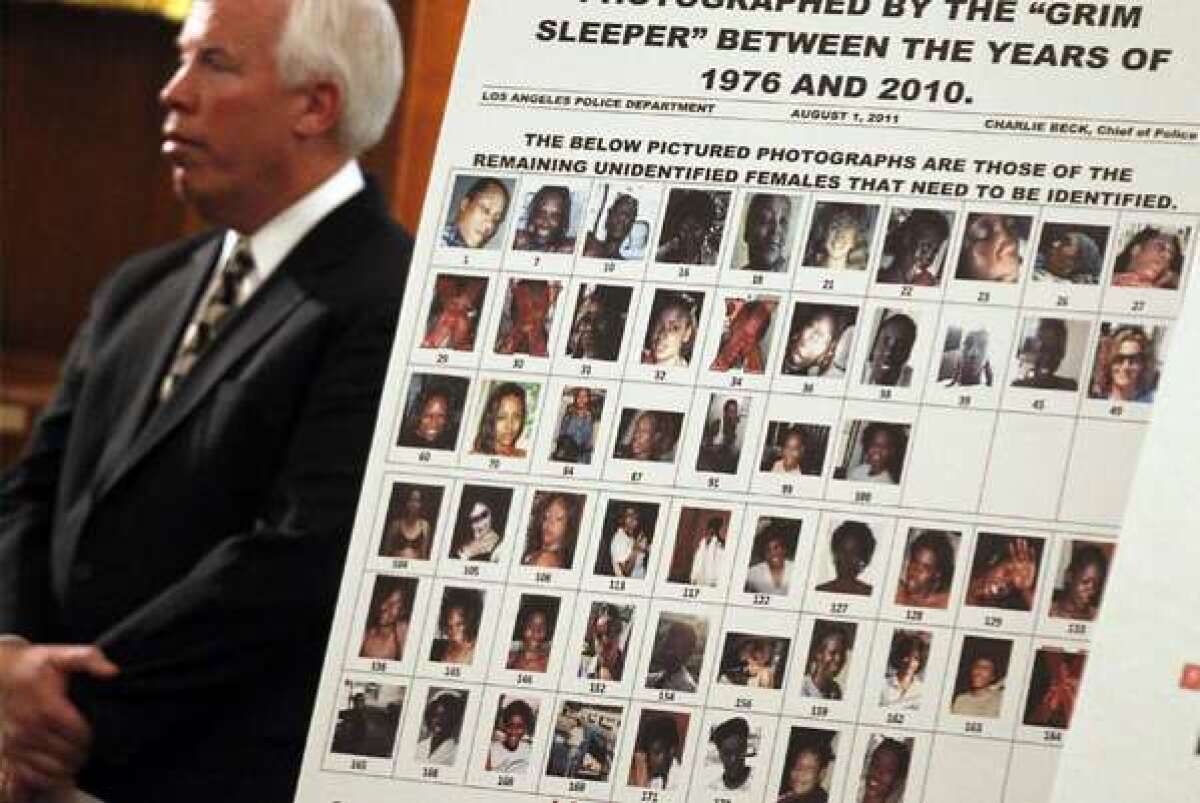

The state of California has been a leader in the use of familial DNA searches -- investigations that seek out crime suspects by taking unidentified crime scene DNA, looking in a state DNA database for people who are partial matches to that sample, and then track down those close relatives of the suspect to help chase down the ultimate target. A familial DNA search helped police nab ‘Grim Sleeper’ suspect Lonnie Franklin Jr. in 2010.

By and large, according a report released Wednesday, California’s system hits the mark: It finds parents, children and siblings in the database dependably, and it’s unlikely to match a sample with a completely unrelated person. But in some cases, the analysis further suggested, the state’s methods could falsely identify more distantly related people -- cousins, half-siblings, and the like -- as first-degree relatives.

That could mean that immediate family members of these mistakenly identified distant relatives could be targeted for further investigation, UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow Rori Rohlfs and colleagues wrote, in a study in the journal PLOS ONE. That raises privacy concerns, especially for members of ethnic groups that are overrepresented in the database, they said.

“It could lead to investigations of people who are not connected,” Rohlfs said, “and doesn’t get you closer to an answer.”

But other experts, including state law enforcement officials, said that California’s tight restrictions on the use of familial searches -- which are a last resort effort to generate leads, applied only in cases of very serious crimes where all other avenues have been exhausted -- make it such that few of the searches are ever conducted in the first place, and those that go forward are conducted under careful oversight.

The PLOS ONE paper reported that the state had performed only 29 familial DNA searches since 2008. According to the California attorney general’s office, the number is around 60.

“The criticism is, you’re disrupting the lives of more people than you have to,” said Los Angeles County district attorney Jackie Lacey. “We think having the certainty outweighs the potential privacy issues.”

The aim in pursuing the study, Rohlfs said, was to determine the rates of true and false identification of California’s familial search method. The state is unique: it has published the statistical method it employs to conduct its searches, which allowed the geneticists to test how well it worked.

Simulating genetic profiles for individuals of various ethnic backgrounds, Rohlfs ran the California search procedure tens of thousands of times. It worked well in finding true first-degree relatives and very rarely turned up hits between completely unrelated people. But it misidentified first cousins as siblings between 3% and 18% of the time, depending on ethnic background. Half-siblings were mistaken as siblings as much as 42% of the time (the video below explains more about the results.)

Study co-author Erin Murphy, a law professor at New York University who has written legal articles opposing familial DNA searches on privacy grounds, said that the findings suggested there was a de facto “shadow database.”

“We as a society have said that certain people, because of their behavior, have forfeited their genetic privacy,” she said. “The thing that I find troubling is that we’re saying that certain people who haven’t done anything but are related to people who have also forfeit their genetic privacy.”

But Frederick Bieber, a well-known authority on familial DNA searches and a medical geneticist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, questioned the study’s methodology, arguing that the simulated data were simplified in ways that “limit the value of the observations.” He added that the study confirmed what is already known, “that interrogation of DNA databases will allow identification of close relatives of persons who left DNA at crime scenes.”

Bieber also took issue with the privacy concerns raised, saying that these searches were used only to generate leads, and are far more precise than methods like traffic stops or stop-and-frisk searches. “There’s no conflict between developing an investigative lead and protecting the privacy and dignity of individuals,” Bieber said.

Officials in California who initiate, vet and approve the familial searches said that they welcomed the new research, because it would help them better understand the capabilities and limitations of the technology. Lacey said that her office would “continue to do things the way we have been, but we’ll continue to be as careful as possible.”

The “Grim Sleeper” case has not yet gone to trial, but another case solved by familial DNA search -- that of accused Santa Cruz rapist Elvis Garcia -- went before a jury last month. On July 18, Garcia was convicted on all seven charges he faced.