Q&A: Southern California, this is your chance to see some of the most ‘extreme’ mammals that ever lived

Let's take a moment to meditate on the awesomeness of mammals.

We mammals are an amazing and diverse group. Among our ranks are the largest animal to ever live on Earth (the blue whale) and the fastest animal that lives on land (the cheetah).

We come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, from the 20-foot-tall giraffe to the tiny Batodonoides vanhouteni, an extinct shrew-like critter that was small enough to fit on your fingernail. And thanks to our revolutionary ability to regulate our internal body temperature, we inhabit every continent on the planet.

The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles is celebrating this amazing mammal diversity in a new exhibition that highlights some of the most unusual members of our clade, which evolved from a group of reptiles.

”Extreme Mammals” originated at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, but curators in Los Angeles have put their own stamp on it by highlighting animals from Southern California. They include the pygmy mammoths of the Channel Islands and our sole surviving big cat from the Ice Age — the mountain lion.

The exhibit was installed under the supervision of Xiaoming Wang, the museum’s curator of vertebrate paleontology who happens to be an extreme-mammal expert himself.

His fieldwork frequently takes him to the badlands of Tibet, where he has found fossils of giant rhinos, some of the largest land mammals that ever lived. This colossal beast weighed four times as much as an African elephant and was bigger than most dinosaurs, except for the long-necked sauropods.

Wang spoke with the Los Angeles Times about why some mammals evolved such extreme adaptations and how paleontologists were able to identify them in the fossil record.

(Make sure to read to the bottom to see Wang’s favorite extreme mammal. You won’t be disappointed!)

The common characteristics of a mammal is an animal that is warm-blooded, has hair and nurses its young, but paleontologists see it differently. Can you explain?

None of these key features are commonly preserved in the fossil record, so we paleontologists are forced to look at other structures — like bones. And lo and behold, we find ear bones that signify a very important transition from reptiles to mammals.

Reptiles have multiple bones in their lower jaw that they use to transmit sound, but they are only good for low-frequency sounds. Shrinking the size of the bones and isolating them in the ear region helped mammals hear the surrounding environment.

It has nothing to do with reproduction or elevated body temperature, but nonetheless, these ear bones are a key feature of mammals. And we can see them today.

How do you define an “extreme” mammal?

We use humans as the reference point for talking about how extreme certain features of a particular animal are. So you’ve got extremely large size — like the giant rhino we call Peggy that was the largest land mammal ever — to the tiniest mammals the size of a bee. But the key is we are measuring it relative to human experience.

What is extreme to us may not be so extreme to others. In the world of elephants, they think they are normal and we are puny.

But humans are extreme in their own way, right?

We are very extreme. We have the highest intelligence among all the animal world, and our brain is the largest relative to the size of our bodies.

Also, we walk on two legs. If you look at the world around us, all the other mammals walk on four legs. We are alone in being bipedal, so in that respect, we are extreme.

What forces cause extreme traits to develop?

One of the advantages mammals have over our reptilian ancestors is that we can generate our own heat to maintain our body temperatures. That allowed us to occupy parts of the Earth that very few other animals could have.

When mammals live in extreme environments, they develop extreme adaptations. For example, in the Arctic region you see extinct woolly mammoths that have hair up to 2 to 3 feet long. That is quite an extreme adaptation.

Let’s talk about some of the Southern California animals featured in the exhibit — like the pygmy mammoth, which lived on the Channel Islands.

Giant mammoths from the mainland went over to the Channel Islands during the Ice Age. At the time, the sea level was 400 feet below the present level, so the distance between the mainland and the shoreline of the island was only four or five miles. The mammoths could easily swim over, and they did.

But once they land on the island they find limited resources there, so they downsize and become tiny compared to the mainland version. They are about half the height of mainland mammoths and about a quarter, or even less, in weight.

You also highlight the Griffith Park mountain lion known as P-22.

That story is trying to showcase what we call extreme extinction. During the Ice Age, there were a lot of megafauna, including an array of five top cats. These predators included the saber-tooths, a jaguar and the American lion, which is the largest cat ever to have lived in North America.

The smallest of the big cats was the mountain lion, and ultimately, it is the only one that survived. So we feature the story of P-22, the survivor of Griffith Park.

In your opinion, what is the most extreme mammal in the exhibition?

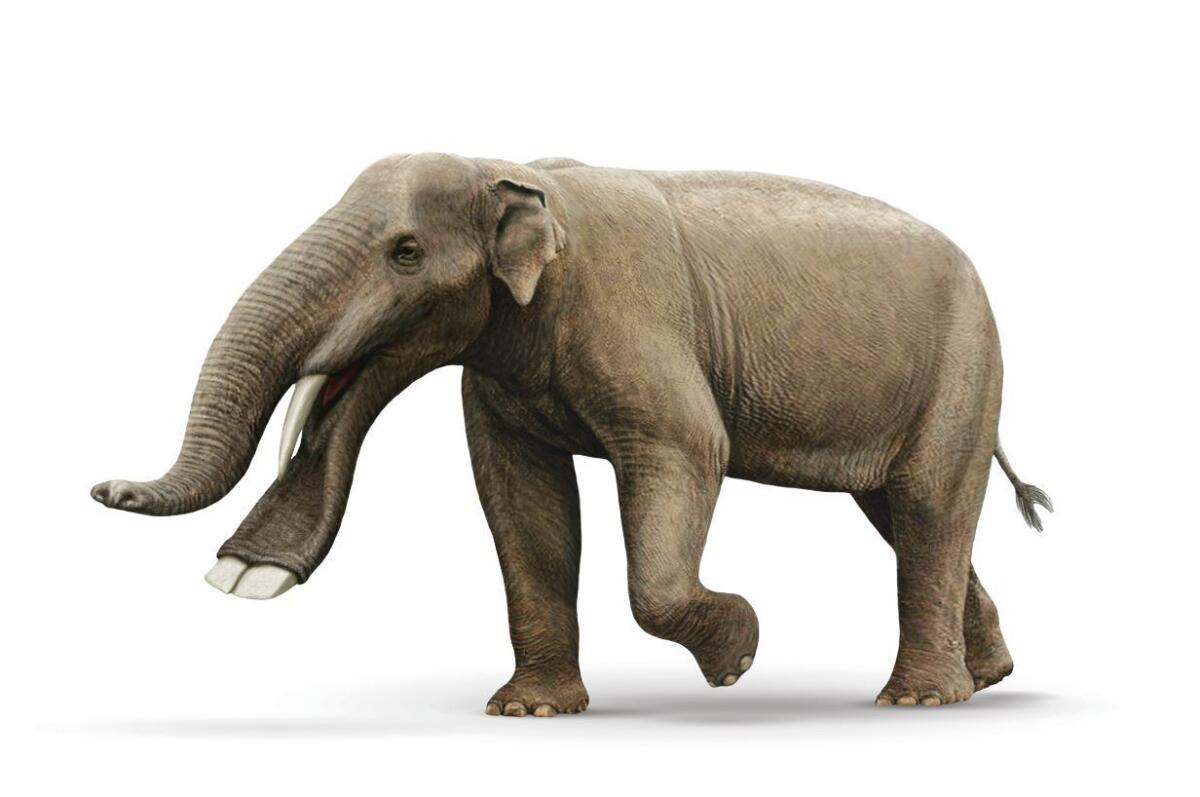

My favorite animal is called the Platybelodon, or the shovel-tusked elephant. It is a distant relative of the modern elephant and its lower jaw has evolved into what looks like a shovel that you would use for clearing snow. It clearly used it to shovel something, but we don’t know what. There’s no other animal we know of that has developed a shovel adaptation.

But I may be biased. I personally collected some of these animals in China.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

FOR THE RECORD

2:48 p.m. May 19: A previous version of this article said Xiaoming Wang’s favorite animal was Amebelodon. It is actually Platybelodon, a close relative.

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and "like" Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

Rising sea levels could mean twice as much flood risk in Los Angeles and other coastal cities

When states have strong guns laws, they also have fewer fatal police shootings