Five ways scientists are going after the Zika virus

To determine whether the Zika virus is indeed responsible for a surge in birth defects, public health officials are drawing on expertise from many disciplines.

These collaborators are galvanized by more than mere scientific curiosity. Having battled Ebola, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, West Nile virus and other scourges, they remain vigilant against any outbreak that could morph into the “Big One” — a deadly and highly transmissible new pathogen for which the public has no natural immunity.

FULL COVERAGE: Zika virus outbreak

“Zika is one of those reminders that everything is worth studying, because we don’t know what the next big one is going to be,” said North Carolina State University entomologist Michael Reiskind, who studies how mosquitoes spread disease. “Biology is incredibly diverse, and when we let our guard down we’re constantly surprised by things. Zika is a perfect example of this.”

Here’s how the puzzle comes together:

Epidemiology

Brazilian Army soldiers inspect a home while canvassing a neighborhood in Recife, part of an attempt to eradicate the larvae of the mosquito which carries the Zika virus. The soliders also discuss ways to prevent Zika’s spread.

Brazilian soldiers inspect a home while canvassing a neighborhood in Recife, part of an attempt to eradicate the larvae of the mosquito that carries the Zika virus. The soliders also discuss ways to prevent Zika's spread. (Mario Tama / Getty Images)

Epidemiologists are poring over, and filling in, a narrative of outbreaks of Zika since its 1947 discovery in Uganda’s Zika Forest.

As population scientists track the virus’ migration out of Africa and into Asia and the Americas, they will pay particularly close attention to evidence that could help them figure out whether cases of microcephaly followed in its wake but were undetected at the time.

The tiny island nation of Yap in the South Pacific may provide the most useful record of Zika infection. Experts estimate that in 2007, between 68% and 88% of residents over the age of 2 were infected with the virus.

Islands can offer a uniquely revealing picture of outbreaks, said Derek Cummings, an infectious diseases specialist at the University of Florida. Their generally small populations tend to be exposed to one new pathogen at a time, and that offers a clearer picture of a virus’ immediate impact and its longer-term health consequences, he said.

If no rise in birth defects is discernible, that could be a sign of poor record keeping. It may also indicate that hundreds or thousands of pregnant women must be infected with Zika to produce one microcephalic infant. If so, the geographically isolated outbreaks of the past may have been too small to prompt a noticeable increase in birth defects.

But epidemiologists must consider other possibilities as well. Among them: Have birth defects been absent before because Africans and Asians have lived with Zika for so long that almost all pregnant women have developed immunity to the virus?

That is known to be the case with another pathogen called cytomegalovirus, said Dr. Sarah Obican, a maternal and fetal medicine specialist at the University of South Florida. If a woman is exposed to cytomegalovirus for the first time while pregnant, she is more likely to give birth to a baby with microcephaly and other neurodevelopmental disorders. But the virus is so widespread that by the time women become pregnant, most of them have already developed antibodies that protect both them and their developing fetuses.

There might be an ominous explanation for the sudden appearance of birth defects apparently related to Zika — perhaps a new mutation in the virus’ genetic code has endowed it with the ability to attack fetal brain tissue.

Some scientists are also asking whether there’s something about Brazilian women — a genetic vulnerability or an environmental factor such as poor nutrition, for instance — that makes their babies more vulnerable to brain-related birth defects when Zika is present.

Brazil’s public health service is already planning studies that will closely track women from the earliest days of their pregnancies until well after they give birth. That way, they can confirm infections when they happen and see how often these illnesses result in birth defects. It will also help them spot new modes of transmission, if and when they arise.

Entomology

A view of Aedes aegypti mosquitos at the epidemiology department of Guatemala City, Guatemala. These are one of two species known to spread the Zika virus.

A view of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes at the epidemiology department of Guatemala City. These are one of two species known to spread the Zika virus. (Esteban Biba / European Pressphoto Agency)

Entomologists, the scientists who study insects, are putting Zika-spreading mosquitoes under the microscope.

Feeding Zika-rich blood to swarms of mosquitoes in their labs, these scientists hope to pinpoint the moment in a mosquito’s 3-week life span at which it becomes capable of spreading the virus. Entomologists must also discern how efficiently each mosquito transmits its viral cargo.

So far, it appears that two mosquito species — Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus — can spread Zika with their bites. These are the same species that spread the viruses that cause dengue, chikungunya and West Nile virus.

As a result, their ranges, feeding patterns and reproductive habits have been extensively studied. That information can help with mosquito control efforts.

Back to topMicrobiology

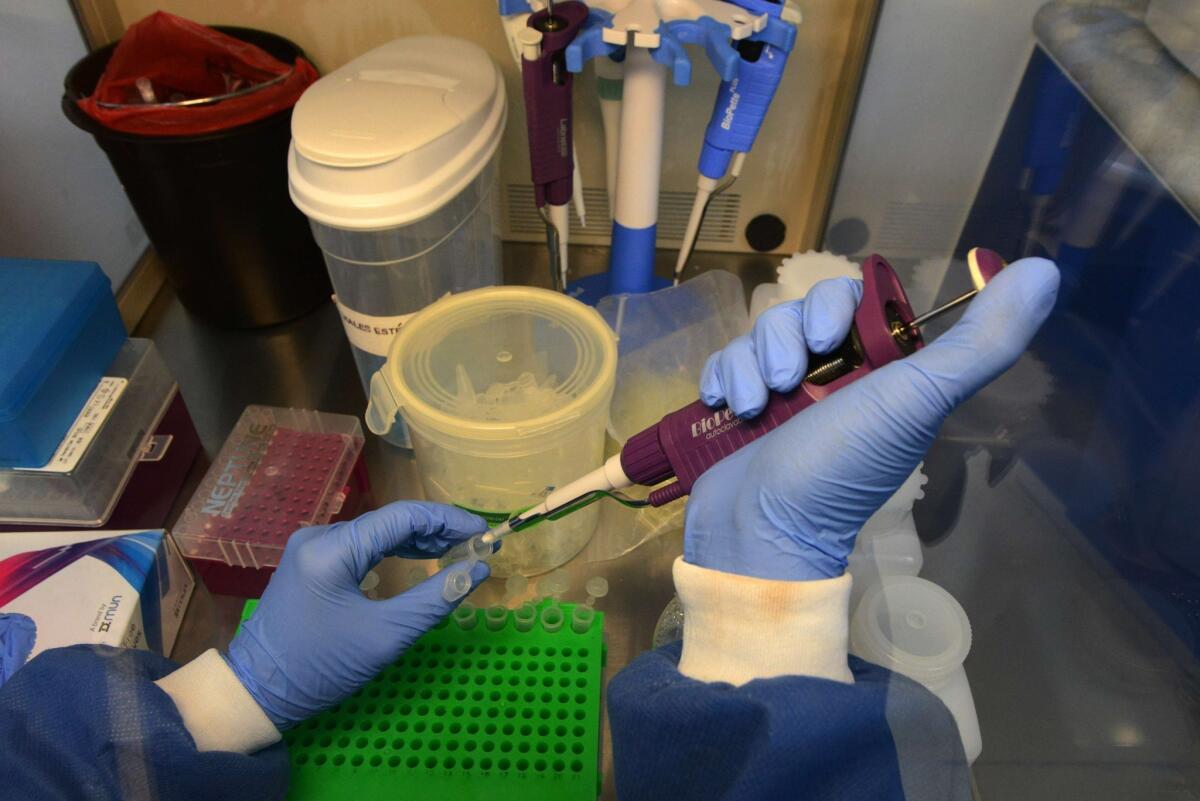

A doctor performs laboratory tests at the National Autonomous University of Honduras Microbiology Research Institute in Tegucigalpa. The university’s microbiology department is leading research on the Zika virus.

A doctor performs laboratory tests at the National Autonomous University of Honduras Microbiology Research Institute in Tegucigalpa. The university's microbiology department is leading research on the Zika virus. (Orlando Sierra / AFP/Getty Images)

Mosquitoes and humans are not the only animals to be studied in the puzzle over Zika.

At the National Institutes of Health, rodents and perhaps other laboratory animals will be exposed to the virus to see how readily they develop infections, how their illnesses progress, and by which of many possible mechanisms the virus reaches and infects a developing fetus, said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Microbiologists will track the virus’ entry into cells, distinguishing which ones they favor, how they replicate, and what — if anything — impedes them.

Some cellular answers are now in hand, and more are on the way. A team of Slovenian researchers recently examined the brain tissue of an aborted fetus with microcephaly whose mother had been infected with Zika in her first trimester. The team found Zika virus throughout the brain but in no other tissues they examined, according to a February report in the New England Journal of Medicine. Given the phalanx of biological barriers the virus eluded to slip into the fetal brain and how widespread it was, the researchers concluded Zika virus is drawn to the growth medium that brain cells provide.

The team also harvested the Zika virus in such a way that its genome can be sequenced comprehensively. That will allow geneticists and virologists to compare the RNA from current strains to those from earlier outbreaks, looking for signs that the virus has evolved in the course of its worldwide journey. Then they must scope out its shape, habits and vulnerabilities, allowing them to plot how — and for how long — the human immune system responds to it, and how vaccines could help.

Dr. Albert Ko, an infectious disease physician and epidemiologist at Yale, said the Zika now circulating in South America is clearly related to the version seen in Yap in 2007. But as it cuts across the Americas, it may well change.

Scientists will also examine samples collected throughout South and Central America now, to see if Zika virus found in the tissue or amniotic fluid of babies with birth defects is in any way different from the virus circulating more broadly in the community.

Ultimately, virologists and immunologists will use the insights they glean to design vaccines that could protect against Zika.

Fauci said NIH scientists are currently pursuing at least two approaches to a Zika vaccine — one used to design a vaccine for West Nile virus and the other used to make a vaccine for dengue virus.

Both of these vaccines are already in early clinical trials, and either or both have the potential be adapted quickly to fight Zika. But Fauci cautioned “we will not have a widely available safe and effective Zika vaccine this year and probably not in the next few years.”

Diagnostics

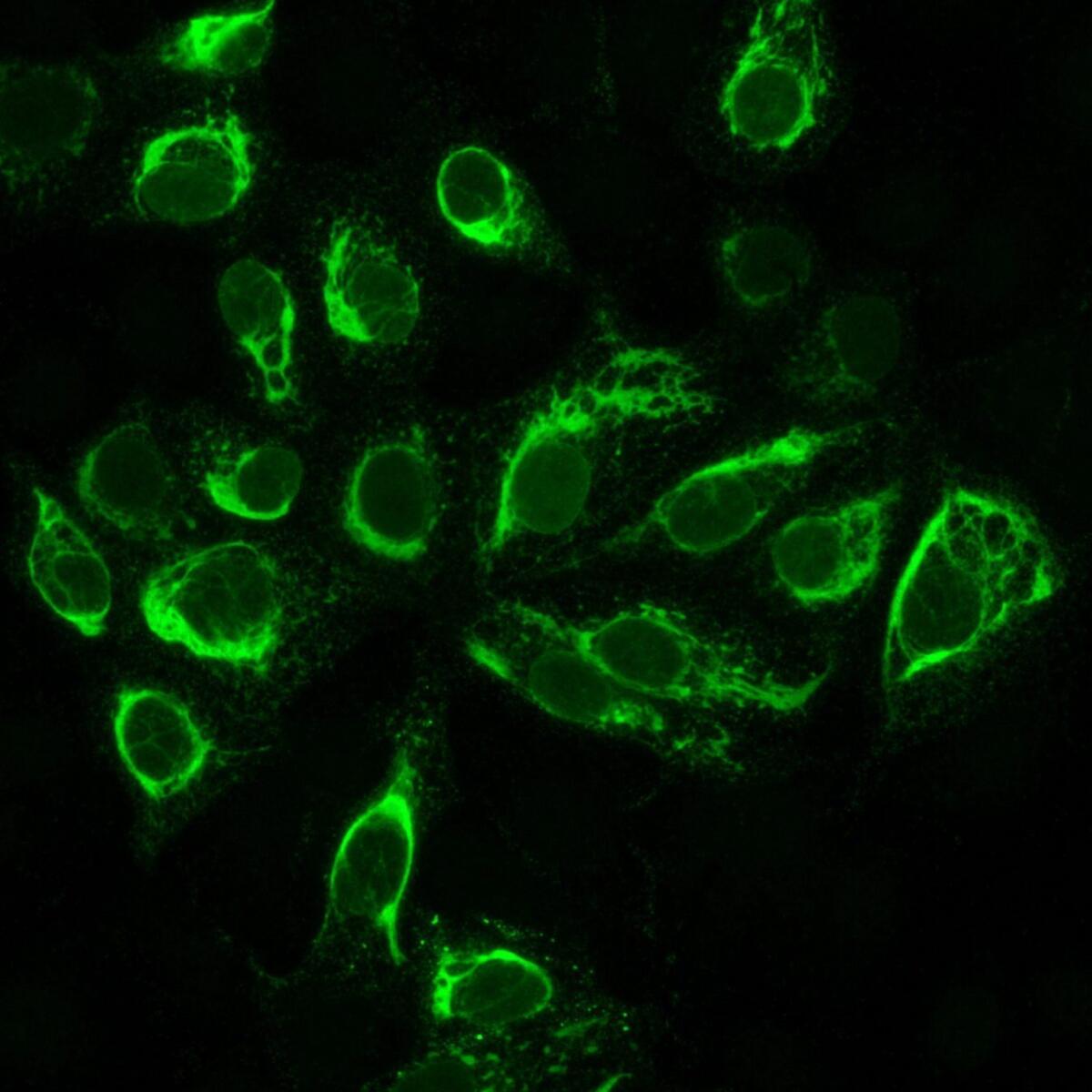

Cultured cells that have been infected with the Zika virus, viewed under a microscope. The cells appear green only if they are infected.

Cultured cells that have been infected with the Zika virus, viewed under a microscope. The cells appear green only if they are infected. (Dr. Erik Lattwein/Euroimmun AG/H / European Pressphoto Agency)

Researchers need to develop inexpensive and easy-to-use blood or urine tests that will reliably identify a Zika infection, past or present.

Some tests currently exist, but they have limited value for the public health officials grappling with the current outbreak. For instance, one available assay detects the genetic residues of the Zika virus only when an infection is ongoing. Another can detect a recent infection, but requires careful sampling techniques, storage and days of laboratory processing.

The ideal assay would be able to confirm whether a patient is infected with the Zika virus or has antibodies suggestive of a past infection. And it could reliably distinguish Zika infection from infection with other viruses that are either in the same family or cause some of the same symptoms but which are not linked to birth defects.

The value of such a test is hard to overstate, said Derek Cummings, an expert in infectious diseases at the University of Florida. It could allow physicians to reassure pregnant women sickened by something other than Zika. It could also help doctors identify and track the pregnancies of women who have been infected by Zika.

In addition, the test would be an invaluable tool for tracing Zika’s pattern of spread through populations with no immunity. Without it, Cummings said, researchers will be hobbled in conducting the kinds of large epidemiological studies that are necessary to tease out Zika’s long-term consequences for the public.

A good field test for Zika could help scientists figure out how the human immune system responds to the virus, and how long that immunity lasts. That might help clarify whether a woman who’s been exposed to Zika before she becomes pregnant might confer protection against any Zika-related birth defects to her future offspring.

Researchers at MIT, the University of Texas and elsewhere are racing to develop Zika assays to fill the void. Even if they work, however, it could take months or years for them to become available to physicians and researchers.

Clinical medicine

A gynecologist examines a rash on the arm of Daniela Rodriguez, who is six weeks along in her pregnancy. She was diagnosed with the Zika virus in Cucuta, Colombia. The most common symptoms of Zika are fever, rash, joint pain, or conjunctivitis.

A gynecologist examines a rash on the arm of Daniela Rodriguez, who is six weeks along in her pregnancy. She was diagnosed with the Zika virus in Cucuta, Colombia. The most common symptoms of Zika are fever, rash, joint pain or conjunctivitis. (Ricardo Mazalan / Associated Press)

Even as they scramble to care for pregnant women with Zika and the babies they bear, fetal and maternal medicine specialists are desperate to solve some key riddles about the virus. They must figure out whether and how it crosses the placental barrier between mother and child, when in fetal development it must be present to do damage, and whether other factors — say, a genetic predisposition or nutritional deficit — must be in place for harm to occur.

Dr. Albert Ko of Yale, who has examined some of the brain scans of affected babies, said doctors are seeing a wide range of neurodevelopmental birth defects in Brazil. While some have mild cases of microcephaly, others have very small brains that are abnormally smooth and riddled with harmful calcium deposits. Abnormally formed retinal and optic nerves, which may affect vision, as well as hearing loss, are also among the birth defects linked to Zika.

That range of outcomes could be a sign that the timing of congenital infection makes a difference, said Dr. Sarah Obican, a University of South Florida maternal fetal medicine specialist who is actively monitoring the pregnancies of women who fear they have been infected with Zika.

“The first trimester is when all the anatomic formation occurs, but the brain’s development continues throughout pregnancy,” she said.

An infection early in pregnancy might be most dangerous because its effects have so long to play themselves out, Obican said. At the same time, she added, “it’s really hard to say the brain cannot be affected in every trimester.”

Meanwhile, pathologists and maternal-fetal medicine specialists will be combing through the fluids and tissues of infected fetuses and babies, looking for clues as to where the virus flourishes. Experts who examined a microcephalic fetus aborted at about 29 weeks’ gestation reported in the New England Journal of Medicine that they found Zika virus in the brain, but not in other tissues they checked. Other teams have found the virus in amniotic fluid.

Obican said she must assume that American women infected with Zika are at no less risk of having babies with birth defects than are women in Brazil. But she, too, wonders whether some genetic or environmental difference may be interacting with the virus to make Brazilian babies more vulnerable.

“We’re nowhere near where we need to be” to make such predictions, she said.

Follow me on Twitter @LATMelissaHealy and "like" Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.