Column One: How a South Pasadena matron used her wits and wealth to create Joshua Tree National Park

Nobody looks at the mural.

Tourists keep their heads down as they walk past. They scan maps, reach for keys, tell their children to use the bathroom. Considering possible destinations, they say, “Did you want to do Hidden Valley and Keys Ranch?” Or, “We can start at Skull Rock.”

They don’t notice the image of a gray-haired woman in a wide-brimmed hat staring out at them. Serene. Determined.

To her right loom stark rock formations and groves of surreal Joshua trees. Flowers bloom at her feet in bright purples and oranges. Look closely and you’ll see a pair of pencil-legged Gambel’s quail and a roadrunner enjoying the desert Eden she nearly single-handedly preserved.

The mural at a federal visitors center is a tribute to the South Pasadena matron who devoted much of her life to saving nearly 1 million acres of desert that would one day become Joshua Tree National Park.

“It wouldn’t have happened without her, that’s the bottom line,” said Lary Dilsaver, author of “Protecting the Desert: A History of Joshua Tree National Park.” “There wouldn’t be a Joshua Tree without her, and in that way she was just as potent as any man.”

In California lore, the story of how John Muir persuaded Teddy Roosevelt to help preserve Yosemite is legendary. In 1903, Muir and Roosevelt camped in the wilderness for three days as Muir showed him Yosemite’s stunning vistas and valleys. Decades later, the matron would convince another president named Roosevelt that Joshua Tree held its own otherworldly beauty. Her story isn’t as well known as Muir’s. But it should be.

Her name is Minerva Hamilton Hoyt. She has been hailed as the first desert conservationist and called the Woman of the Joshua Trees and the Apostle of the Cacti. She even has a cactus named after her: Mammillaria hamiltonhoytea.

Born on a cotton plantation in Durant, Miss., in 1866, she fell in love with the desert in the 1890s while traveling west by train with her husband, Dr. Sherman A. Hoyt. Later, she recalled being transfixed by this “world of strange and inexpressible beauty, of mystery and singular aloofness, which is yet so filled with peace.”

The couple settled in a leafy estate on Buena Vista Street in South Pasadena, where Hoyt embraced the region’s civic life — as president of the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra, head of the Boys and Girls Club of Los Angeles, and a founding member of the Valley Hunt Club, which started the Tournament of Roses.

Her teas and garden parties merited write-ups in newspapers. And her lush five-acre garden was listed by Forbes as among the top 14 most important gardens in America.

Still, the desert beckoned.

“Those early days in the California town were busy and interesting, yet the call of the desert … remained persistent and I found myself frequently invading it on horseback or in a buckboard” wagon, she wrote decades later in a letter to desert conservationists.

She described camping in the desert in the 1910s with a maid as her only companion: “During nights in the open, lying in a snug sleeping bag, I soon learned the charm of a Joshua Forest. … Above, the bright desert constellations wheeled majestically toward the west, a timepiece for the wakeful.”

'I soon learned the charm of a Joshua Forest.… Above, the bright desert constellations wheeled majestically toward the west, a timepiece for the wakeful.'

— Minerva Hamilton Hoyt

Some historians say her devotion to the desert appeared to grow deeper in the wake of two tragedies. She lost her son in infancy and her husband died in 1918. She was 52 and never married again. As the years went on, she turned to the peaceful landscape for solace from her pain.

Hoyt’s transition from desert lover to desert activist began in the 1920s, spurred in part by the desecration of a flat plain that lies along what is now California Highway 62, between Interstate 10 and Morongo Valley. It was known as Devil’s Garden.

When Hoyt arrived in California, the area was abundant with immense barrel cactuses, spiky yuccas, fuzzy chollas and splashes of wildflowers. But as desert gardens became popular in Los Angeles in the 1910s, landscapers ripped up plants and carted them off to the city. By the 1920s, the desert wonderland had been stripped bare. (Today, nearly 100 years later, the flora of Devil’s Garden have never fully recovered.)

Hoyt described similar devastation in an appeal to conservationists in 1929. “Over thirty years ago I spent my first night in the Mojave desert of California and was entranced by the magnificence of the Joshua grove in which we were camping and which was thickly sown with desert juniper and many rare forms of desert plant life,” she wrote.

“A month ago … I visited the same spot again,” she continued. “Imagine the surprise and the shock of finding a barren acreage with scarcely a Joshua tree left standing and the whole face of the landscape a desolate waste, denuded of its growth for commercialism.”

Hoyt vowed to protect other desert areas from a similar fate.

Behind the story: Uncovering the history of Minerva Hamilton Hoyt »

In 1928, the California State Park Assn. hired landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (whose father designed New York City’s Central Park) to identify areas that should be included in a state park system. By then, Hoyt had established a reputation as a desert expert, and Olmstead asked her to prepare a report on the outstanding features of Inyo, Mono, Riverside and San Bernardino counties.

In Southern California, Hoyt selected 1 million acres extending from the Salton Sea to Twentynine Palms. However, she soon decided this wilderness, with its magnificent boulders and bizarre plants, deserved national park status.

Today, Joshua Tree National Park is celebrated on Instagram feeds and on Facebook. It’s the backdrop for music videos, fashion spreads and commercials. But for much of U.S. history, the desert was reviled as a wasteland, hot and lifeless. When the explorer and politician John C. Fremont first described the Joshua tree in 1844, he called it “the most repulsive tree in the vegetable kingdom.”

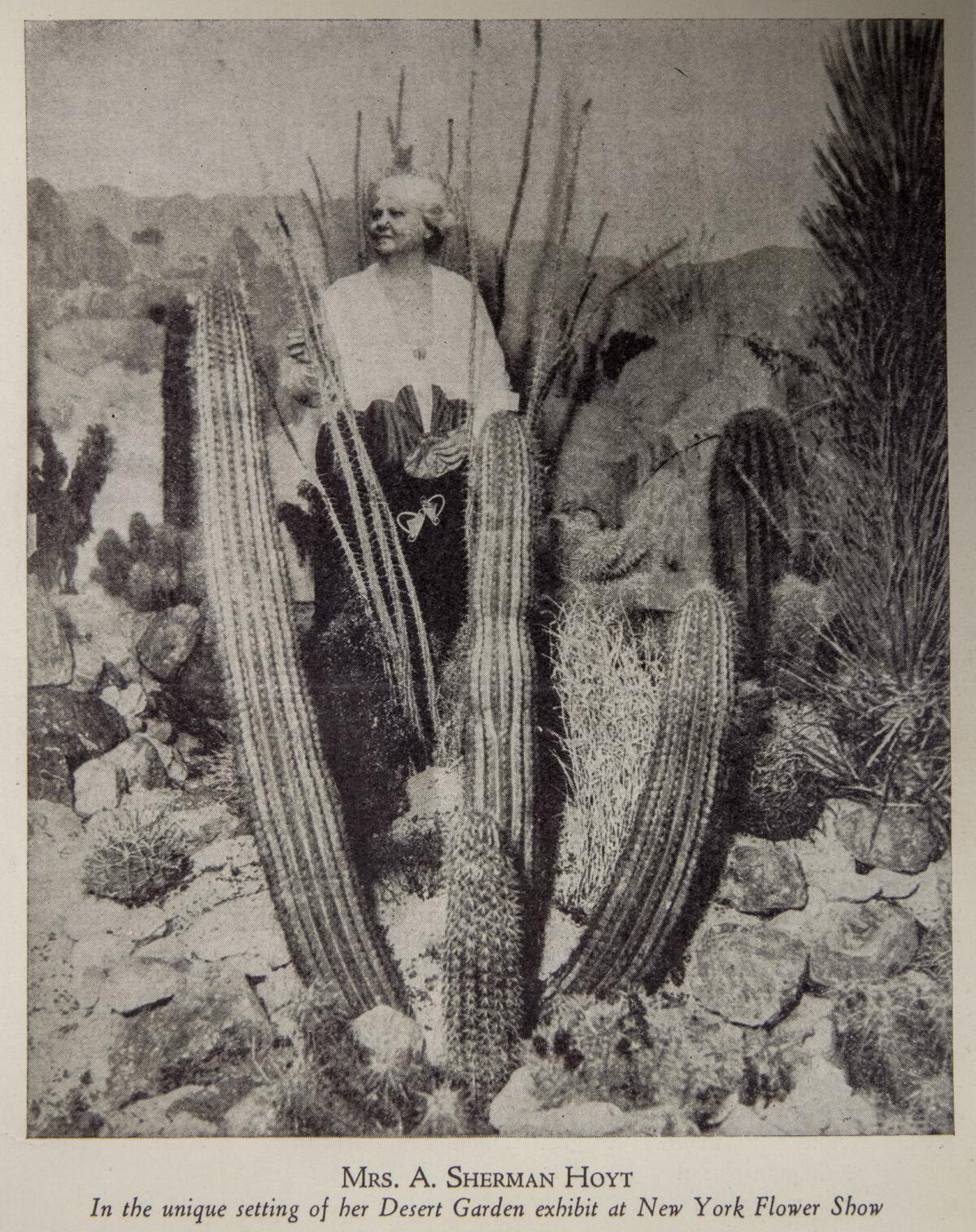

In order to persuade people to protect the desert, Hoyt knew she would first have to persuade them to love the desert. And so in 1929 and 1930 she staged three lavish and increasingly extravagant installations at flower and horticultural shows in New York, Boston and London.

For the Garden Club of America’s Flower Show, she filled seven freight cars with desert rocks, plants and sand and had them shipped to New York. Desert flowers were flown out twice a day to preserve the “velvet texture” of their blooms. She told fawning newspaper reporters that she stored the airlifted plants in the bathtub in her hotel. (There is no evidence that she suffered any guilt about desecrating her beloved desert in order to save it.)

The Associated Press reported that her London exhibition was so popular that a policeman had to be stationed in front of the cacti and stuffed coyotes to “keep the folks from crowding too hard against the ropes.”

Hoyt won gold medals at the shows, but more important, she amassed an army of powerful allies. After seeing her show in New York, William Jardine, agriculture secretary under President Calvin Coolidge, said Hoyt had “succeeded in bringing the West to the East.” In England, Princess Mary was said to have stopped by.

When Hoyt founded the International Desert Conservation League in March of 1930, the honorary vice presidents of the board included museum directors and university presidents, and the founder of the U.S. Forest Service.

By 1934, Hoyt’s group had become powerful enough that the National Park Service was forced to take her proposal for a new park seriously. And so, in March of that year, the agency dispatched Roger Toll, superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, to the desert.

“Toll was a major player, and his opinion carried or destroyed a number of places,” Dilsaver said. “If he said no, that was the end of it.”

Hoyt met Toll in Palm Springs with her chauffeur and the desert botanist Philip Munz. On her desert excursions, Hoyt often looked as if she was hosting a tea — dressed in long skirts, hats and heels. They spent three days touring the desert together at a relentless pace, but the weather was cold and unpleasant and Toll was not impressed.

In a letter to the director of National Parks, Toll acknowledged that parts of the region might be valuable for local and state use, but added it is “lacking in any distinctive, superlative, outstanding feature that would give it sufficient national importance to justify the establishment of a national park.”

He recommended that Hoyt’s proposed 1-million-acre monument be reduced to a particularly nice grove of Joshua trees on 138,240 acres.

Hoyt was furious. She demanded that Park Service officials send someone else to survey her park, someone who understood the desert, someone who understood California. A few months later, they did.

“She did not hold political position, but she knew the power brokers and they listened to her,” Dilsaver said. “The fact that she was able to override Roger Toll’s 170-page report denying the park indicates the extent of her power.”

Hoyt had an iron will, but she softened it with a Southern hostess’s charm.

In a 1935 telegram to Arno B. Cammerer, director of the National Park Service, she wrote that she was “delighted” to hear he was in California and asked if he would meet to discuss the park. If his wife was accompanying him, Hoyt said, she could “ARRANGE A PARTY IN MY GARDEN FOR YOU BOTH.”

In a telegram a year earlier, she invited another federal official to a picnic to discuss the park, “WE WONT TAKE NO FOR ANSWER CAN MEET YOU AT TRAIN AND MAY I PLACE MY AUTOMOBILE AT YOUR DISPOSAL WHILE HERE PLEASE WIRE MY EXPENSE.”

Around the same time, Hoyt decided to use her extensive network of connections to reach out to the president of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

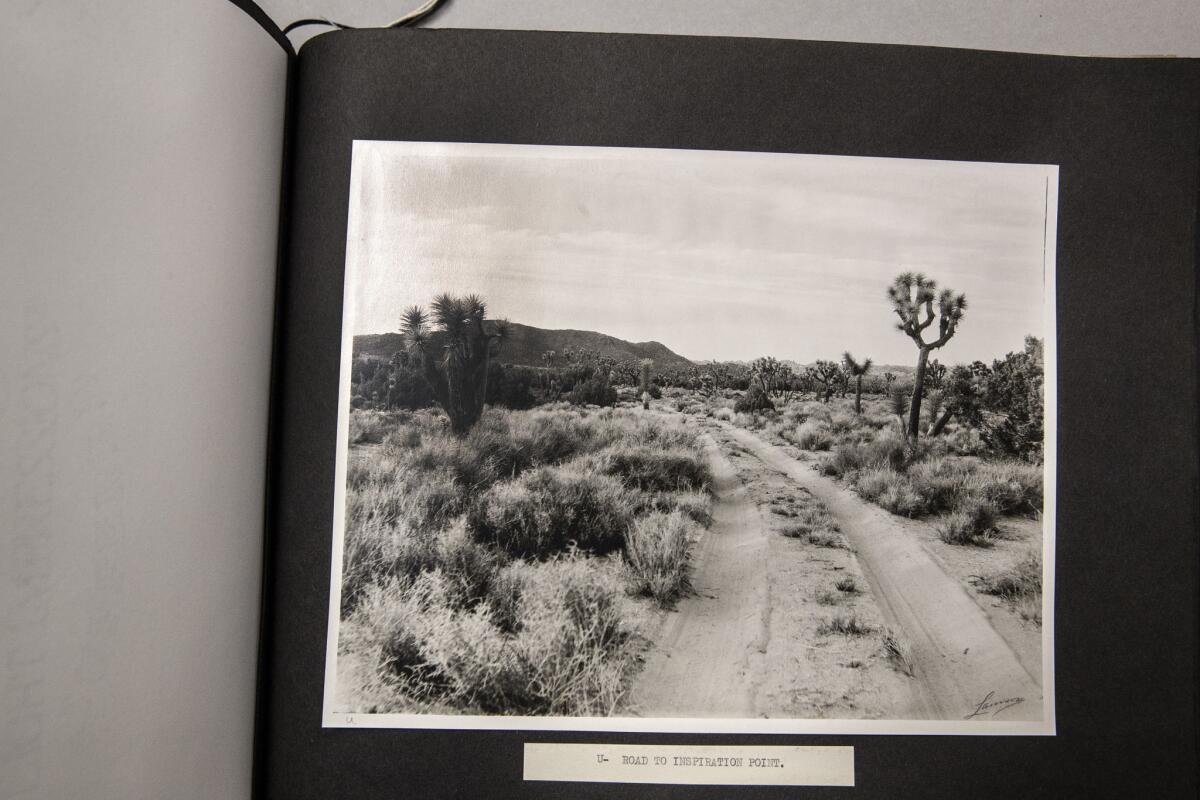

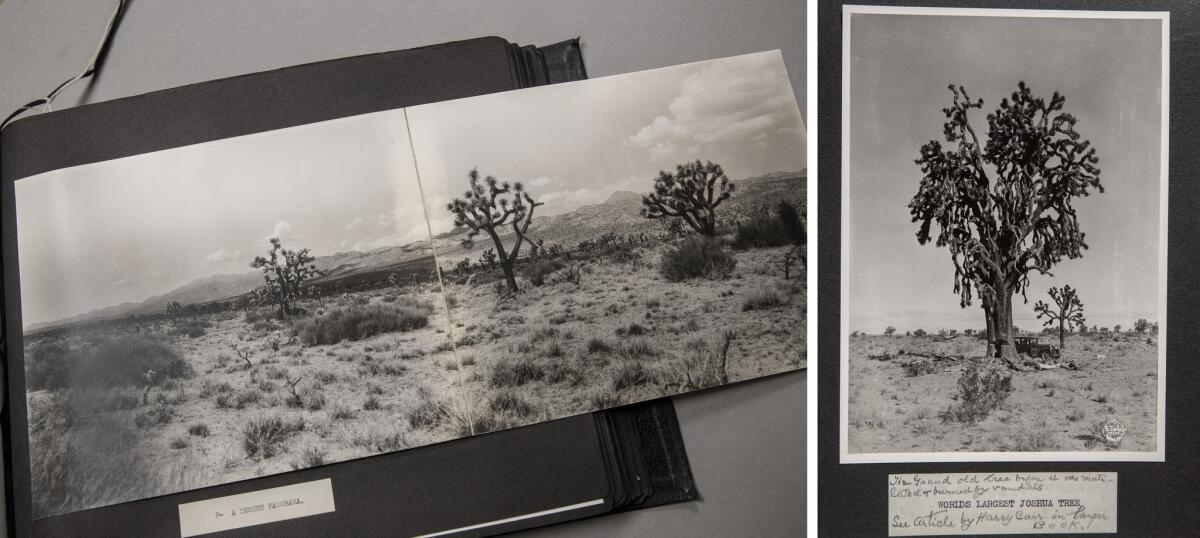

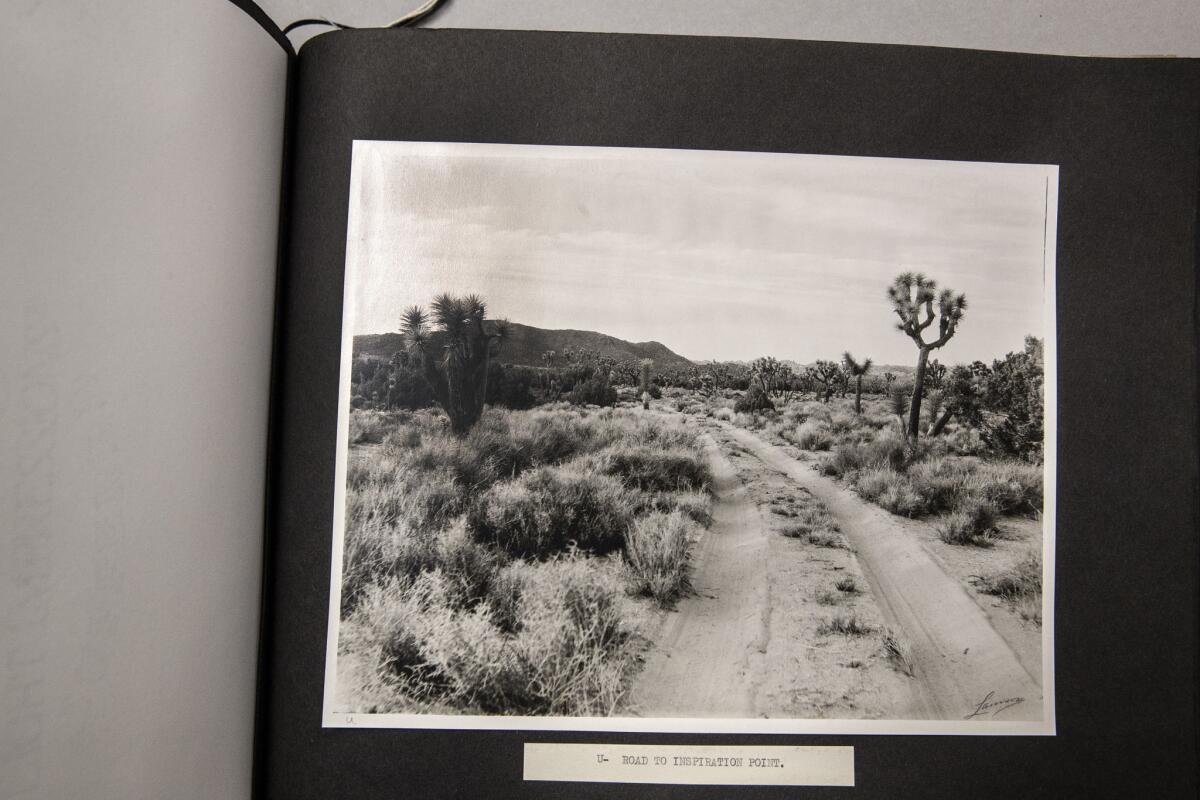

She received a letter of introduction from California Gov. James Rolph Jr. Then, she sent the president two photo albums, and they would change everything.

A copy of one album still exists, tucked away in a dark, refrigerated storeroom in the archives of Joshua Tree National Park. Unless you asked for it however, you would never know it was there.

“Today we would probably do something in the video realm, if we were trying to sell people on the park. She didn’t have that capability,” said Joe Zarki, a retired historian at the park. “This was her way of getting the visual significance of the park to a really high-powered audience in Washington, D.C.”

Turn the pages of the album and you can envision what Roosevelt saw.

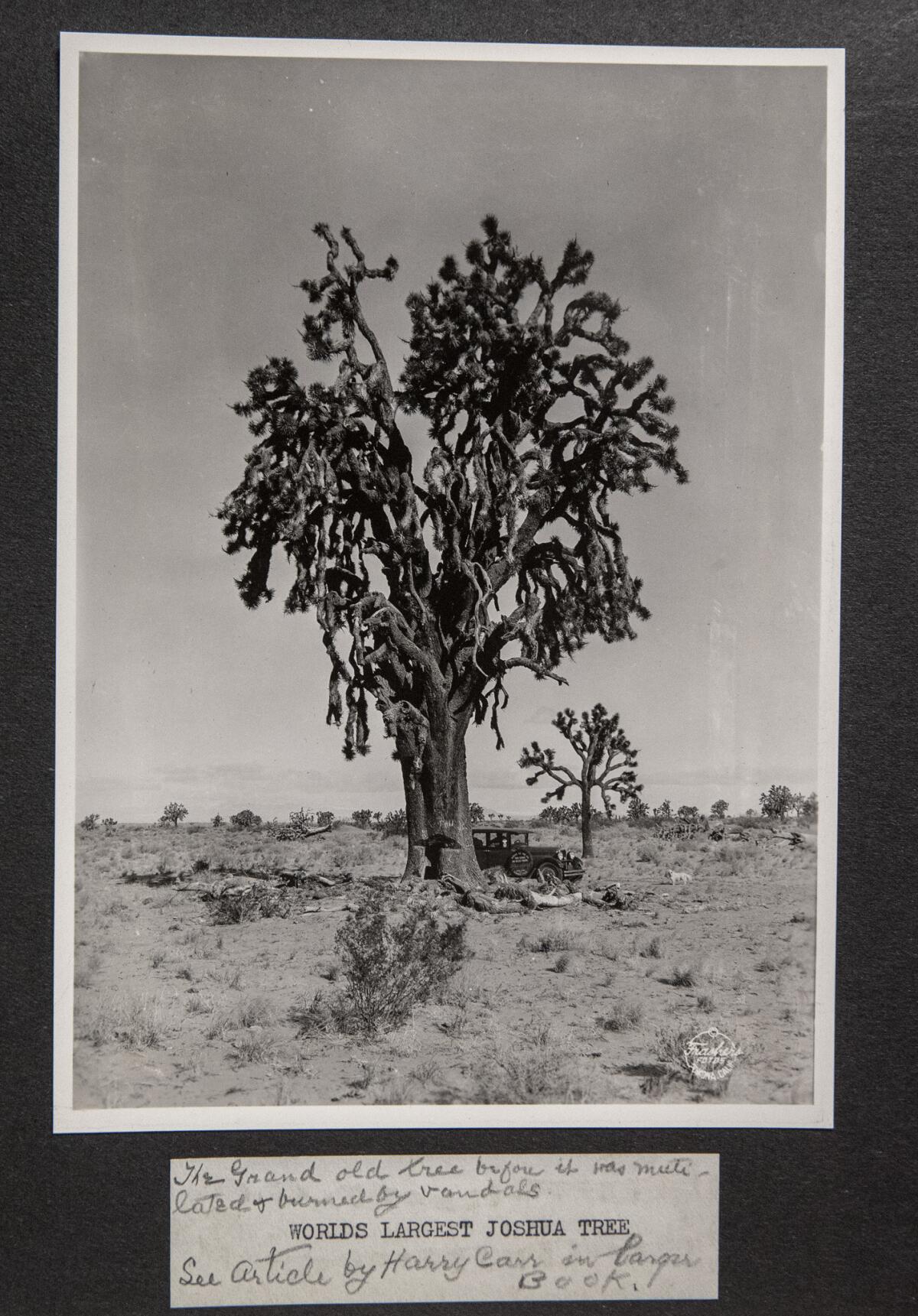

There are a few news clippings, but the album mostly holds black-and-white photographs commissioned by Hoyt and taken by Stephen Willard, a famous landscape photographer of the day.

They are faded but timeless — towering, multi-armed Joshua trees, flatlands dotted with creosote and smoke trees, spindly ocotillos and the thrilling view of a real life desert oasis. There are even a few panoramas that were created by taping two or three images together.

In the second half of the book, the gardener in Hoyt shines through, with photos of flowers in full bloom hand-painted to approximate their true glory.

Henry Harriman, president of the Chamber of Commerce of the United in States, delivered the albums to the president in June of 1934. Harriman later wrote to Hoyt that Roosevelt went over the pictures with care: “He desired that I express to you his great appreciation of your kindness and of his intense interest in the work you are doing.”

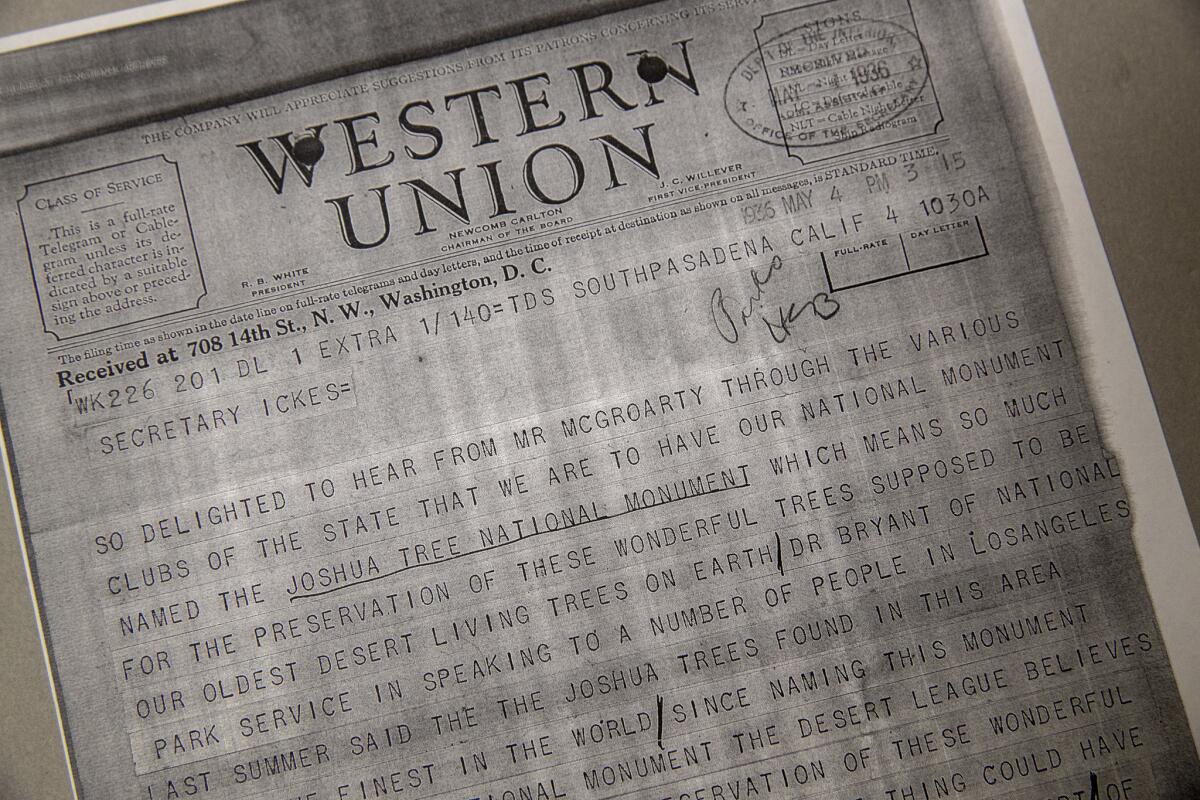

Hoyt’s multiple lines of attack eventually paid off. In 1936, FDR signed Proclamation 2193, establishing Joshua Tree National Monument on 825,340 acres — almost 700,000 acres larger than what Toll had recommended.

But even then, Hoyt’s fight wasn’t over.

Much of the land set aside for the monument was in private holdings. Hoyt then worked to get landowners such as the Pacific Coast Railway to relinquish their hold on the land.

Hoyt died in December of 1945 at the age of 79. She was buried at Mountain View Cemetery and Mausoleum in Altadena.

But still, the battle to preserve her beloved park waged on. In 1950, Congress gave in to mining interests and slashed the park’s hard-won land holdings by almost a third. That land wouldn’t be returned to the monument until 1994, when Joshua Tree officially became one of the country’s 60 national parks.

It took several decades for the park to grow in popularity, but in the last few years its attendance has exploded, growing from 2.5 million visitors in 2016 to 2.8 million in 2017.

Zarki can imagine how Hoyt would have responded to the headline-grabbing desecration of the park during the government shutdown, and to the industrial-scale projects being proposed and built along its edges. “We need people like her now more than ever,” he said.

Hoyt has not been entirely forgotten. She has her mural, painted in 2014. And there is a plaque in her honor in the shade of the visitor’s center. Each year the Joshua Tree National Park Assn. gives out the Minerva Hamilton Hoyt Desert Conservation Award to someone who has worked to preserve the desert.

In 2012, one of the park’s peaks was renamed. It is now known as Mt. Minerva Hoyt. It is a stately mountain. But almost nobody knows it’s there.

Produced by Sean Greene