Coronavirus Today: When live music becomes a science experiment

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, May 3. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

We can be so sick of wearing masks that we decide we don’t need them anymore. We can listen to politicians on TV or Twitter saying life can — and should — return to normal and decide to believe them because we want them to be right. We can wish all we want for the pandemic to be over.

Unfortunately, none of that will actually make the coronavirus go away.

Fans of live music have been learning that lesson the hard way, my colleague August Brown reports. The recent Coachella and Stagecoach festivals provided the perfect natural experiment to test the hypothesis that if people ignore the coronavirus, it will return the favor.

Goldenvoice thrilled many music fans — and unnerved others — back in February by announcing that the sister festivals would drop all COVID-19 precautions. No checking for proof of vaccination or a recent negative coronavirus test. No rule about masking up in crowded venues. Nothing.

So attendees went to the desert and partied like it was 2019.

In the reporting week before the first Coachella act took the stage on April 15, the nine cities in the region reported 109 new coronavirus cases, according to Riverside County data. Over the following three weeks, the cities reported another 754 cases. That averages out to 251 per week.

In all likelihood, the festivals weren’t the only factor. Infections have been on the rise everywhere as mask and vaccine rules fall by the wayside while newer, more infectious versions of Omicron spread. New cases rose 121% across Riverside County over the past two weeks. Statewide, they’ve increased 56% during that time. And nationwide, the average number of new cases per day over the prior week jumped by 58%, from 35,989 on April 15 (the first day of Coachella) to 57,020 on May 1 (the last day of Stagecoach).

“The virus is definitely flowing,” Dr. Matt Willis, Marin County’s health officer, told my colleagues Rong-Gong Lin II and Luke Money. “People need to know the likelihood of an exposure in the community is increasing.”

Live music events are certainly contributing to the trend. Pent-up demand for concerts has fans buying tickets at a furious pace, with no end in sight. Here’s one measure: In late April, Live Nation typically has five to 10 tours booked for the following year; as of last week, there were more than 40 planned for 2023.

The shows happening now are all but guaranteed to help the coronavirus spread.

“I don’t see how the concert industry is going to do what government and society haven’t been able to do, which is enforce mandates,” Randy Phillips, the former head of AEG Live, told Brown. “At this point, we’ve got to live with it.”

Liz Sánchez tried to do just that. The 20-something Angeleno said she felt a bit uneasy when she arrived in Indio for Coachella’s first weekend. She had come close to selling her ticket after learning there wouldn’t be any safety rules in place. Ultimately, she opted to go with her friends, taking some comfort in the fact that “no one seemed to be worried about getting COVID-19.” She didn’t even wear a mask.

Sánchez began to regret that decision on her drive home from the desert. She was more exhausted than the festival alone could account for. “I got tested a couple days later, and it was positive for COVID-19,” she said.

Performers are vulnerable too. Justin Bieber and Elton John have tested positive while on tour this year. John Mayer has come down with COVID-19 twice.

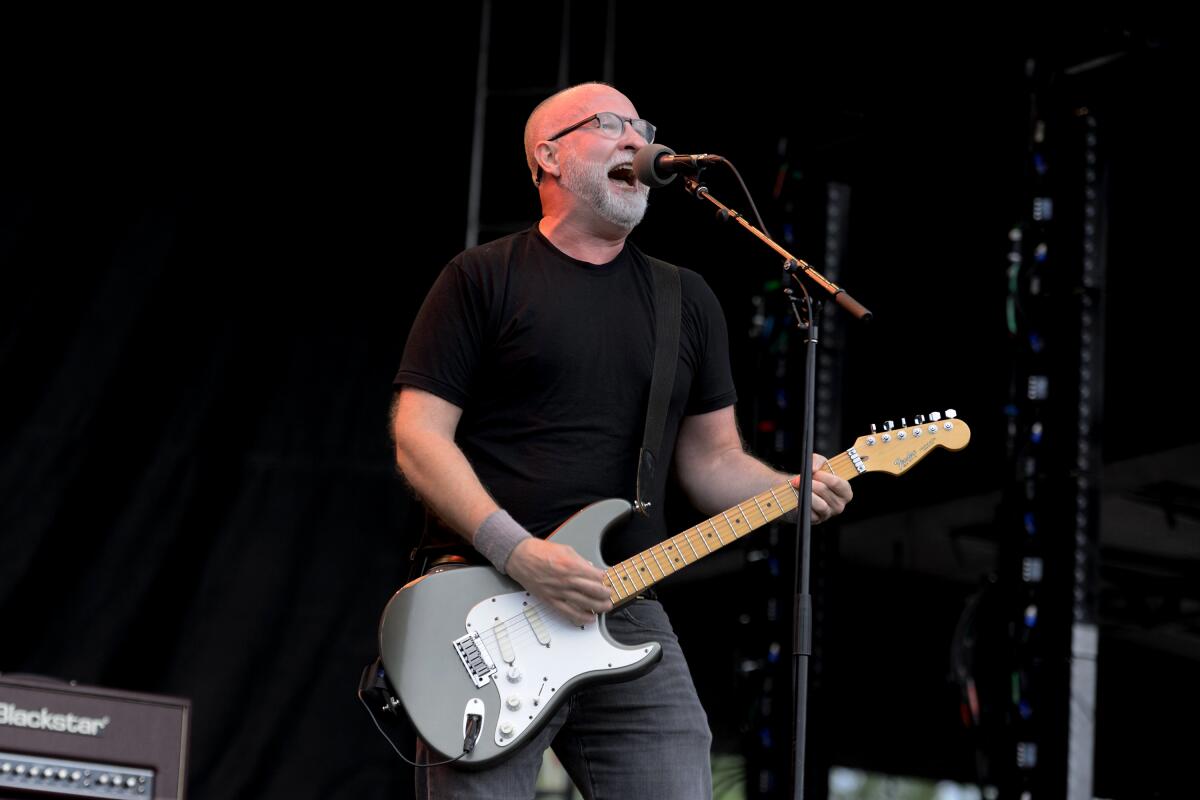

Bob Mould, the former frontman for Hüsker Dü and Sugar, has been particularly vigilant about COVID-19 safety. Before he embarked on a three-week tour last fall, he made sure everyone in his band and on his crew was fully vaccinated. All of them took coronavirus tests every other day to catch a potential outbreak early.

Mould risked alienating his fans by telling them he expected them to wear masks that covered their noses and mouths. If they weren’t down with that, or with showing proof of vaccination if a venue required it, he had a solution:

“It’s OK to miss this show. It’s OK to miss this tour. There’ll be more in the future,” he explained in a video. “We’ll miss you, but if you’re having hesitancy on any level, I recommend you get a refund.”

He went back on the road again in late March with a slightly more laid-back attitude. When my husband (a Bob Mould superfan) and I went to see him play the Troubadour in West Hollywood last month, the majority of the fans were maskless, though proof of vaccination was required.

Apparently, he relaxed his rules even more at a subsequent show in the Bay Area. The coronavirus took notice. A few days later, Mould tested positive for an infection.

“I blame myself for not being enough of a hard ass,” Mould told Brown while isolating in Seattle. “I don’t think there’s any question we have to be wearing masks when we congregate indoors with drinking and yelling and singing.”

Melanie D. Sabado-Liwag, a professor of public health at Cal State L.A. who sometimes moonlights as an EDM DJ, said that thinking still applies for events like Coachella too.

“Even outdoors, there’s still some risk,” she said. “You might be walking by someone without a mask who is unvaccinated. You just don’t know.”

By the numbers

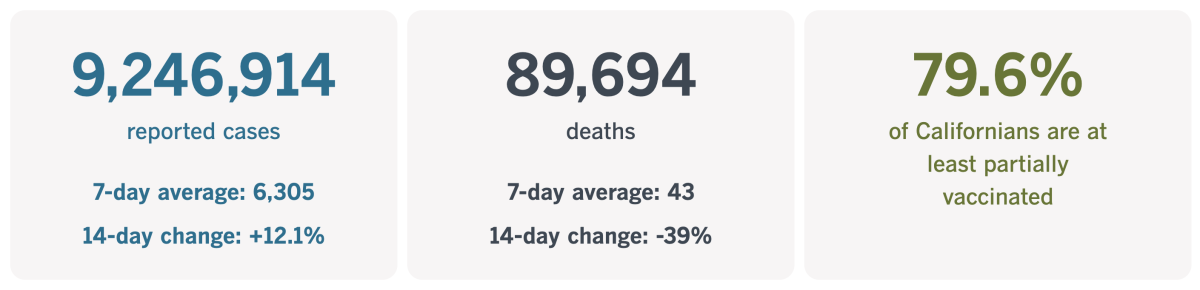

California cases and deaths as of 5:40 p.m. Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Did the pandemic prompt teens to come out as transgender?

Erica Anderson is a clinical psychologist who specializes in treating transgender youth. In 2019, when she was working at the adolescent gender center at UC San Francisco, the clinic saw 162 new patients over the course of the year. In 2021, the number of new patients had more than doubled, to 373.

It could have been a sign that transgender and nonbinary teens felt more comfortable coming out, and it would’ve been in line with survey data from 2017. Federal health researchers had asked high school students about their gender identity and found that 1.8% described themselves as transgender. Five years earlier, the best estimate for that figure was 0.7%.

But Anderson suspected that wasn’t the whole story. The easing of social stigma may have made it easier for teens to speak up. But perhaps the pandemic had something to do with it as well.

She had previously noticed a growing population of transgender adolescents who hadn’t seemed to question their gender much before they hit puberty. Some of them embraced the transgender label only briefly before shifting to something else, like nonbinary, gender-questioning or gay. To further muddle the picture, many of these teens had been diagnosed with conditions like anxiety, depression and autism before they’d expressed any desire to transition.

“A fair number of kids are getting into it because it’s trendy,” Anderson told the Washington Post in 2018.

Did that kind of thinking help explain the post-pandemic spike in patients at the UCSF clinic? It wasn’t a popular idea, but it was one she couldn’t dismiss out of hand.

The teens she saw had similar experiences. Their schools had shifted to online learning. Unable to socialize in person, they spent more time on social media. Transgender influencers and activists got them to consider the possibility that if they felt uncomfortable with their bodies, perhaps it was because they were trans.

The teens soaked up advice about how to change their name and their pronouns and, in some cases, how to bind their breasts. Then they went on platforms like TikTok, Instagram and YouTube to experiment with new identities.

Being transgender isn’t contagious — “I can assure you, transgender identity is not something one catches,” Anderson said in a 2019 interview — but that doesn’t mean questioning teens weren’t influencing one another. She’d seen it happen before, with conditions like eating disorders and repressed memory syndrome.

“What happens when the perfect storm — of social isolation, exponentially increased consumption of social media, the popularity of alternative identities — affects the actual development of individual kids?” Anderson told my colleague Jenny Jarvie. “We’re sailing in uncharted seas.”

The answer matters because some of the treatments for transitioning teens carry significant risks, including decreased bone density and sterility. Those risks may well be worth it if the patient goes on to live a happier life with a new identity. But some patients may later regret the treatment. (Statistics on how often this happens are unreliable and highly contested.)

“The risk of over-diagnosis is real, as evidenced by the growing number of young adults wishing to ‘detransition,’” France’s National Academy of Medicine advised this year. With that in mind, the academy urged doctors to be cautious in their use of hormones and puberty blockers for younger patients.

Not everyone who treats transgender patients is on board with the idea that social pressures are prompting teens to identify as trans.

“Is it trendy to be one of the most marginalized and vulnerable groups?” asked Dr. AJ Eckert, medical director of the Gender and Life-Affirming Medicine Program at the Anchor Health Initiative in Stamford, Conn.

Anderson, now 71, has helped hundreds of teens transition. Sometimes she thinks she’d be better off focusing on adult patients, though she continues to treat adolescents.

She wants her colleagues to keep in mind that there are people like Keira Bell, a British woman who started taking puberty blockers at 16 and had a mastectomy at 20 but later regretted it. Bell sued the clinic that treated her, claiming she received “experimental treatment with life-altering outcomes” after only “a series of superficial conversations with social workers.” (She won.)

With some patients, there may never be easy answers, but Anderson is used to that.

“I have a dictum: When in doubt, doubt,” she said. “Questioning is a good thing.”

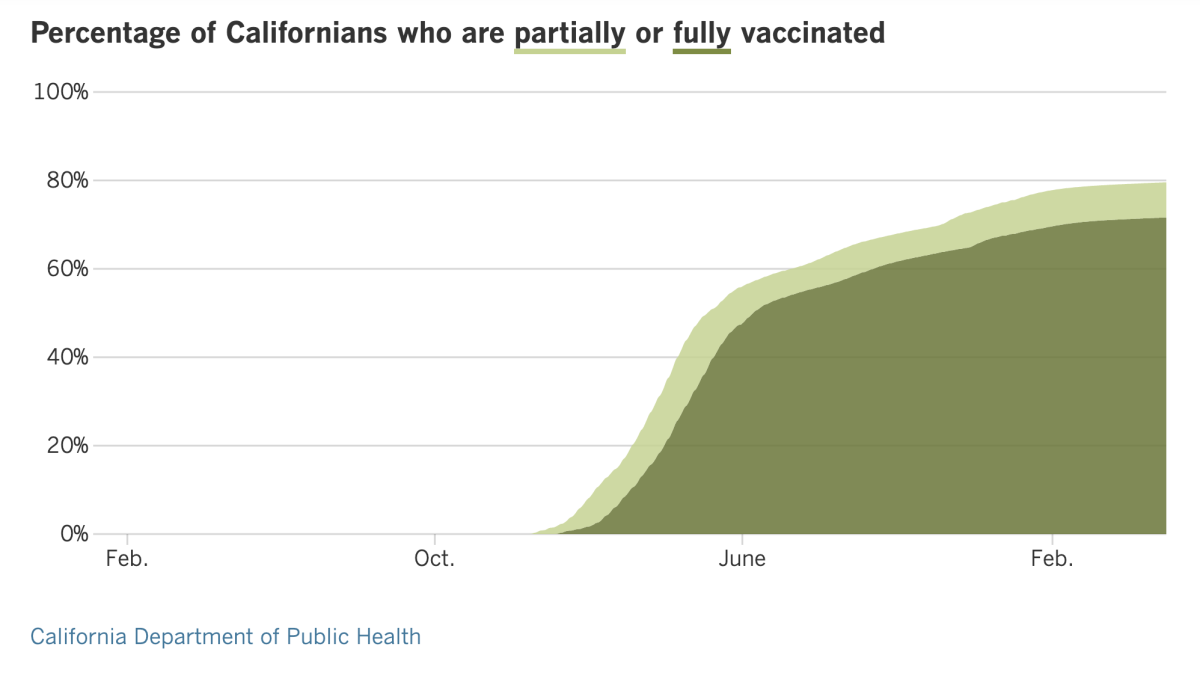

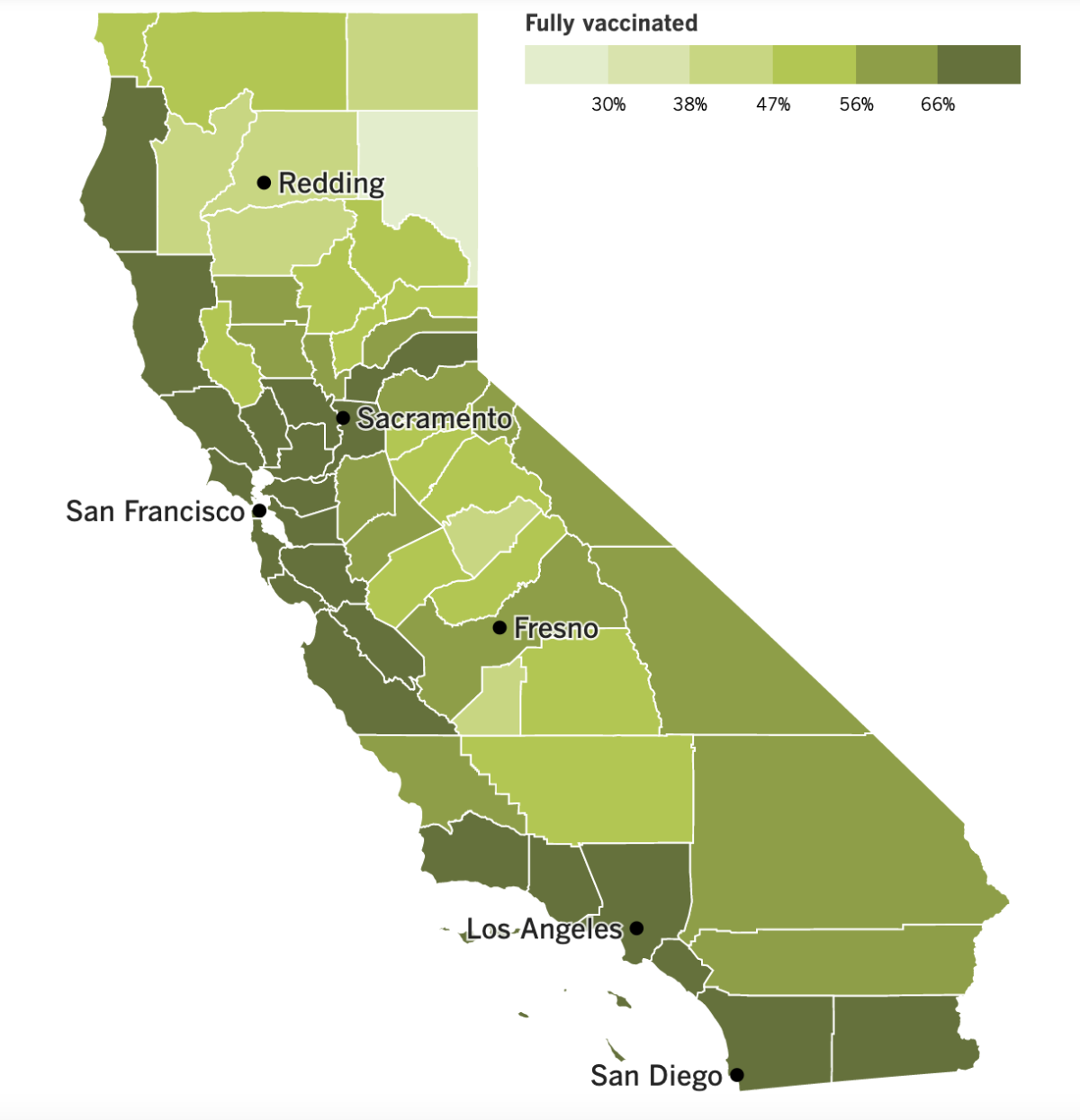

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

As mentioned earlier, the coronavirus is making a comeback in California. Cases are up nearly 30% over the past week, and hospitalizations have risen 7%, including a 13% increase in ICU admissions.

The upward trend has some health officials wondering how much worse things will get and whether it will be necessary to bring back some of the recently lifted COVID-19 rules, like universal mask mandates and vaccine verification requirements. The state has been averaging 6,305 new cases per day over the last week, and its weekly per capita case rate once again exceeds 100 per 100,000 residents — enough to meet the threshold for a high rate of coronavirus transmission.

Cases in Los Angeles County are up 40% week to week. That’s not bad enough for Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer to call it a “surge,” but it is “pretty significant,” she said. Outbreaks are climbing in schools, workplaces and nursing homes, and viral levels in the county’s wastewater systems have nearly doubled in the last two weeks.

A pair of new Omicron subvariants, dubbed BA.4 and BA.5, could make things worse. They’ve only been implicated in two cases here so far, but BA.4 appears to be fueling a new surge in South Africa, where the weekly case count has tripled in the last two weeks.

That worries experts here because 90% of South Africans are thought to have immunity to earlier Omicron variants, either through vaccination or a past infection. So much for the idea that our recent Omicron wave left us with some lasting protection.

Ferrer expressed nostalgia for the not-so-long-ago time when “it seemed like every few months we heard about a potential new variant of concern.” Now that cycle time is down to “weeks,” she lamented, “and this has been especially true with Omicron.”

Here’s something else she said Tuesday that bears repeating: “When folks ask why public health remains cautious, it is because every time there’s a new variant that is more infectious or potentially more infectious, that means it can spread more easily. You have to be super careful about those that are most vulnerable in our communities. And here in L.A. County, that’s millions of people. It’s not a tiny number.”

That helps explain why L.A. County decided to keep requiring travelers to wear masks when taking public transit and inside transportation hubs, including Los Angeles International Airport and Hollywood Burbank Airport. Both Long Beach and Pasadena, which operate their own public health departments, aligned themselves with the county’s rules. That means masks are also required at Long Beach Airport.

The rule went back into effect at 12:01 a.m. Friday and led to some strange juxtapositions. In theory, passengers waiting to board a flight should be wearing masks in the terminal, then can take them off when they’re seated in a crowded aircraft. Likewise, people flying into the county who haven’t worn a mask the entire time are supposed to put one on as soon as they deplane. In reality, few masks were seen on passengers’ faces at LAX Sunday night, though security officers, airline employees and other workers sported light blue surgical masks.

Elsewhere in L.A., Supt. Alberto M. Carvalho said L.A. Unified schools should delay enforcement of its COVID-19 vaccine requirement for students until July 1, 2023, at the earliest. That would align California’s largest school district with the expected timeline of a statewide requirement. (The vaccine mandate for teachers and other employees would remain in place.)

Carvalho said a delay would make it easier for struggling students to catch up. The school board will vote on the issue next week.

“There are many students, thousands of students, who are not making adequate progress because they’re being taught in a modality that does not necessarily match their needs,” he said. “Those students absolutely need face-to-face instruction. If the scientific conditions are what they are, we ought to remove the barriers and invite them back to the schoolhouse.”

Speaking of vaccines for children, Moderna has formally asked the Food and Drug Administration to authorize its COVID-19 shot for kids younger than 6. The company submitted data showing two low-dose shots protected infants, toddlers and preschoolers, although the shots lost some effectiveness during the Omicron surge.

The FDA has penciled in meetings with its independent vaccine experts on June 8, 21 and 22 to review Moderna’s application and a similar one from Pfizer and BioNTech. For now, 18 million younger children are still waiting for their first opportunity to get a COVID-19 shot.

A new study suggests Omicron is more likely than earlier coronavirus variants to cause upper airway infections among hospitalized children. Researchers examined the records of nearly 19,000 children and teens 18 and younger who were admitted to hospitals and had coronavirus infections. During the pre-Omicron era, 1.5% of these pediatric patients experienced an upper airway infection like croup, a type of bronchitis. After Omicron, that rate climbed to 4.1%. The average age of these patients fell from 4.4 years before Omicron to 2.1 years after.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: What will happen to me if I get COVID-19 while traveling abroad?

It depends on which country you’re visiting when you get sick, but you could be in for a miserable vacation. And it may take awhile for you to get home.

Let’s start with that last part. Most travelers are required to provide proof of a negative coronavirus test within a day of boarding a flight to the United States. You’ll need that negative test result even if you’re a U.S. citizen or permanent resident, and even if you’ve been fully vaccinated and boosted.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says the test you take must be a viral test that can detect an active infection. A rapid antigen test falls into that category. (Plan ahead and pack some in your luggage.) So do PCR tests, along with a slew of other options with acronyms we’re not used to seeing here (HDA, TMA, NEAR, etc.). A complete list is available on the CDC website.

There are a few exceptions to the test requirement. Infants and toddlers under age 2 don’t need to prove they’re coronavirus-free.

Neither do people who have recovered from an infection that began within the previous 90 days. That’s because you can keep testing positive for up to three months even if you’re no longer sick.

Instead, you’ll need an official letter from a licensed healthcare provider stating that you have fully recovered. A letter from a public health official will work too. The letter should include your name and date of birth, and these should match the information on your passport. This, along with the proof that you tested positive within the past 90 days, is considered your “documentation of recovery.”

Other exemptions are possible but rare. For instance, you may qualify if you have to return to the U.S. right away for lifesaving medical treatment, or if you are fleeing a place where you’re in immediate physical danger and it’s not safe to wait around for your test result to come in.

If you become sick while you’re abroad, you should isolate for at least five days. You can end your isolation once you’ve gone 24 hours without a fever (without taking medicine to bring your temperature down) and your other symptoms are improving. Wait at least 10 days to travel. If you need medical care, you can ask the closest U.S. embassy to suggest a provider.

As you might imagine, an unexpected isolation period could make your trip more expensive. Insurance policies are available to help cover medical bills, the cost of an extended hotel stay, any portion of your trip you have to cancel, and other expenses. Lots of countries actually require this insurance, including Chile, Indonesia and Israel. Be sure to check if your destination is one of them.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

This is Desha Johnson-Hargrove. Her husband, Jason Hargrove, was a bus driver in Detroit who vented in a Facebook Live video about a passenger who coughed repeatedly without covering her mouth, endangering her fellow bus riders. His complaint was prescient: He died of COVID-19 11 days later at the age of 50.

Johnson-Hargrove shared her husband’s story in Time magazine, where she pleaded with readers to follow the advice of public health officials and “stay home. I can’t stress enough that you don’t want to be this person sitting here with your loved one gone.”

Johnson-Hargrove appears in “The Color of Care,” a documentary executive produced by Oprah Winfrey that premiered Sunday on the Smithsonian Channel and is available on Facebook and YouTube through May 31. It focuses on a now-familiar theme: the racial inequities in America’s health system that the pandemic made impossible to ignore.

Winfrey told my colleague Marissa Evans she was inspired by the heartbreaking story of Gary Fowler, who sought COVID-19 care at multiple Detroit hospitals and was turned away from all of them. He died at home, leaving behind a written record of his struggle to breathe.

Evans asked Winfrey what she learned about racial health disparities by working on the documentary.

“I think my biggest misconception was that it was about health insurance, that it was about having access financially, and if you didn’t have the money, then you couldn’t get the care that you needed,” Winfrey said. “What COVID laid bare is that inequities in so many other areas of your life also contribute to the major disparity when it comes to healthcare.”

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.