West African Ebola victims were more likely to survive if also infected with malaria, study finds

Just eight months after West Africa’s Ebola epidemic was declared extinguished, researchers are reporting a curious and potentially revealing fact about the deadly viral infection: It was less likely to kill people who were also in the grips of malaria infection.

At a treatment center run by Doctors Without Borders in Liberia’s capital, Monrovia, the average death rate among 1,182 patients with confirmed Ebola virus infection was a punishing 52%.

But among the many factors that affected a patient’s prognosis, including age, gender and the extent of Ebola disease progression, researchers discerned another factor: Ebola patients who were also infected with the parasite that causes malaria were, on average, 20% more likely to survive their ordeal.

Among the 19% of patients who arrived at the clinic in the throes of both Ebola and malarial infection, 58% survived. Among the remaining 81%, only 46% left the clinic alive.

The protection conferred by malarial infection was evident even among older Ebola patients and among patients with very high Ebola virus loads — both factors that typically increased a patient’s likelihood of succumbing to the disease. And patients whose malarial infection was most severe had the highest probability of surviving Ebola. In 83% of such cases, the patients survived their brush with the deadly hemorrhagic disease.

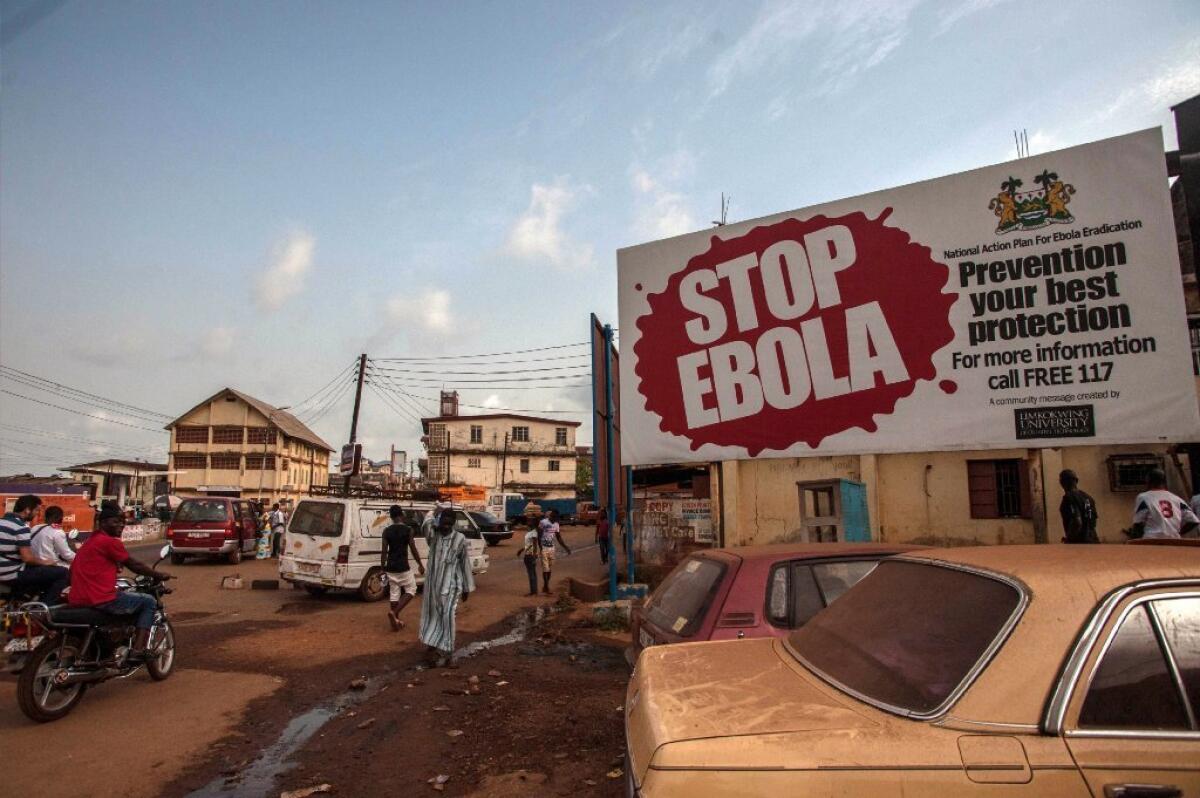

The new finding, published Tuesday in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, offers new insights into Ebola and sets the stage for the discovery of treatments that could tame the virus. Limited local outbreaks of Ebola have bubbled up across Africa periodically since 1976. But beginning in December 2013, it roared through the West African nations of Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea, claiming the lives of 11,325.

Alongside Ebola during that period, the more widely recognized scourge of malaria continued to thrive throughout Western Africa. Malaria, whose symptoms mimic those of early Ebola infection, was so common among the populations affected by Ebola that physicians and public health officials were initially confounded.

By the time the latest study was underway, physicians were automatically treating all incoming patients for malaria, even before their infection status was known.

The survival benefits of having malaria were evident among those who were being treated. But, since malaria treatment was given to all patients whether or not they had the parasitic disease, it’s unlikely that the increased survival rates among some were due to malaria treatment.

“This was a really surprising finding,” said coauthor Emmie de Wit, a virologist with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. When researchers and clinicians would see Ebola patients with sky-high levels of malarial parasite in their blood, “we would say, ‘Oh, man, this person is not going to make it,’” De Wit said.

To discover that patients’ odds of survival were improved by their malaria was an “intriguing observation,” said study coauthor Kyle Rosenke, a molecular biologist with NIAID’s Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Mont. But, he added, “what it means we don’t know yet. We’re going to spend the next few months—or years—to tease that out.”

De Wit and Rosenke will work with laboratory animals in the coming months to better understand the mechanisms by which an active malaria infection might improve an Ebola patient’s odds of survival.

If they can discover how a co-occurring malaria infection fortifies a patient against Ebola, the insight could prompt the development of drugs that mimic the effect without making patients sick.

That would be a more refined approach than earlier efforts to heal using malaria. Before penicillin was discovered, some physicians sought to cure late-stage syphilis by infecting the patient with malaria. In more recent years, some have sought to fight HIV infection and Lyme disease by infecting patients with malaria — treatments that have been denounced by bioethicists.

The latest research revives, at least, the idea that underlies such efforts: that malaria may play some role in priming the immune system to fight other diseases.

“One thought is that having an active malaria infection puts your immune system in a heightened state of alert,” said Rosenke. Even though malaria is a parasitic infection and Ebola a viral infection, the body’s response to malaria parasites may somehow also prime the body to fight against Ebola virus, he suggested.

It doesn’t always work that way, says Derek Cummings, a research professor at the University of Florida’s Emerging Pathogens Institute. More frequent are known cases in which coinfection with a second disease overwhelms the body’s immune system, making the patient more likely to die.

And in some cases, the combined attack of two infections so provokes the human immune system that a person succumbs to a massive overreaction by his or her own defenses.

That, says Cummings, raises the possibility that malarial infection ties up some part of the immune system that might overreact to Ebola infection, dooming a patient. As researchers explore further, they will glean new insights into the complexity of pathogens and their interactions with each other and the humans who become their hosts, Cummings said.

“This reminds us that we as hosts are a complicated ecology for pathogens, and that there are lots of interactions that pathogens encounter when they infect us,” he said.

Follow me on Twitter @LATMelissaHealy and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE FROM SCIENCE

Before Zika: How the U.S. fought illnesses from pests in the past

Acetaminophen use in pregnancy linked to kids’ behavioral problems

A 400-year-old shark? Greenland shark could be Earth’s longest-lived vertebrate