‘We walk with Hillary’: Why an L.A. congressman tells voters -- in 2 languages -- to caucus

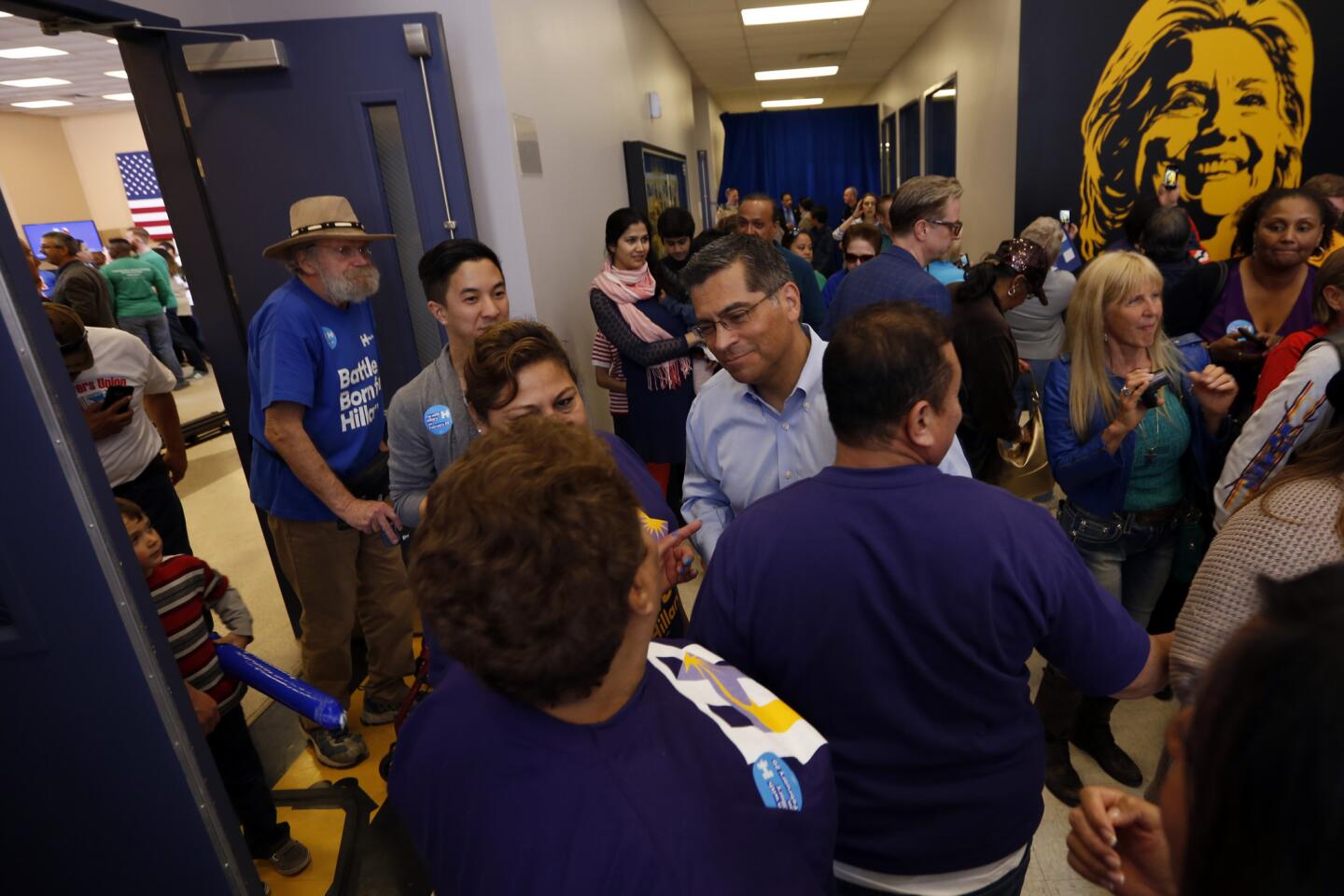

Rep. Xavier Becerra (D-Los Angeles) attends a Hillary Clinton rally at Painter’s Hall in Henderson, Nev.

Reporting from Las Vegas — Xavier Becerra could be spending time at home with his daughter in Los Angeles, in the congressional district he has represented for 23 years. He could be in Washington preparing for the next meeting of House Democrats or raising money for colleagues.

But instead he’s here in Las Vegas, traveling from union halls to drab campaign phone bank centers to convince voters that Hillary Clinton should be the next president of the United States.

As he makes the rounds for Clinton, speaking to voters in both English and Spanish, he is also laying the groundwork for his own second act.

He’s one of the most prominent Latinos in Congress, chairman of the House Democratic Caucus, and running for a 13th term. But his opportunities to move up in the House leadership are limited unless someone retires or steps down.

“I don’t know what might happen,” he said, “but I’m not going to be caught flat-footed.”

That is at least one of the reasons he devoted 36 hours here last weekend to walk the streets of Nevada speaking to potential caucus-goers, and picking up the phone to make a pitch for Clinton.

In a state that is 28% Latino and critical to Clinton’s closer-than-expected battle with Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), Becerra is a valuable stand-in for the former Secretary of State – an affable Spanish-speaking politician able to connect with voters as a big city congressman who was the first in his family to attend college.

And he knows as well as anyone that, if Team Clinton prevails in the election, there could be a reward for his grassroots efforts.

Becerra has quietly stumped for Clinton across five states since endorsing her in August. He has devoted six weekends, acting as a surrogate on local television and telling people in Colorado, Iowa, Nevada, New Hampshire and South Carolina why they should vote for the woman he’s known for nearly 25 years. (He doesn’t mention that, when Clinton battled Barack Obama for the nomination eight years ago, he was on Obama’s side.)

On the trail last weekend, in advance of this Saturday’s caucuses, Becerra was leaning against a railing, holding an “Iron Workers for Hillary” sign as Clinton addressed cheering union members representing iron workers, bricklayers and teachers.

THIS IS WHAT IT’S LIKE when a California congressman campaigns in Nevada >>

The setting was a union hall in the Las Vegas suburb of Henderson. A folding wall has been opened to create more space as organizers tried to fit in more union members who had been waiting – some since dawn – in a line that wrapped the building.

“Hill-Yes!” one woman yelled. Others waved signs reading “Estoy Contigo,” or “I’m With You” in Spanish.

Becerra nodded when Clinton briefly thanked him onstage. Photographers and others trying to get a better view of the candidate pushed by, not recognizing him.

After the speech, Clinton lingered to shake hands and talk to the crowd.

Becerra rushed in the opposite direction to talk Clinton up to the local and national press in the back of the room. It’s less glamorous than commanding the stage, but critical to her potential success.

Becerra has been in this position before.

SIGN UP for our free Essential Politics newsletter >>

His 2008 endorsement of Obama led to an offer to join that administration as U.S. trade representative. But Becerra turned that down, suggesting he was worried trade wouldn’t be a major focus of the administration. (The Obama administration wasn’t pleased the congressman took weeks to make up his mind.)

Last year, he contemplated running for retiring Sen. Barbara Boxer’s seat, but decided to stay in the House despite an uncertain path to power there.

He has less than a year left in his term as chairman of the House Democratic Caucus, but if he hopes to be the first Latino House leader, he’ll have to wait. Democratic matriarch Nancy Pelosi, 75, has given no indication about when she will retire, and her No. 2, Maryland Rep. Steny Hoyer, 76, is expected to move into that job once she does.

That leaves Becerra, 58, with some choices. In 2018, if Sen. Dianne Feinstein retires, he could pursue the seat she has held for 23 years. Or ask to be placed on the powerful House Budget Committee. Or perhaps there is a role for him should Clinton become the party nominee.

He wants to do more in federal politics, but isn’t focused on a particular job, he said. He’s heard speculation he could be a vice presidential pick, but declines to speculate himself.

Xavier Becerra, a U.S. representative from Los Angeles, makes a call at the Las Vegas home of Maria Gray, second from left, in support of Hillary Clinton.

“Shame on me if I don’t try to do more with what I have. It would be ... a terrible thing to waste this opportunity to try to make a difference,” he said. “I’m closer to my final year doing this work than I am to my first year. I want to make a difference, and there are so many ways.”

Becerra hosts fundraisers and dinners with colleagues and supporters during the Washington work week and campaigns for local candidates around stumping for Clinton. On Sunday, he traveled to Houston to campaign for Democratic Rep. Gene Green.

As he walked out the front door of Clinton’s rally at Painter’s Hall, a dozen Service Employees International Union members, who took a bus from Los Angeles at 2:30 a.m. to make it in time, mob Becerra, squeezing him into hugs. They block the exit, speaking rapidly in Spanish and prompting the congressman into several group photo configurations. The rally wasn’t originally on his schedule, and a staffer has to repeatedly pull Becerra away so he can run to the car and make the next of his seven events.

It was a whirlwind trip to Vegas, with Becerra talking to Latino and other community groups, knocking on doors and reminding volunteers why they are working so hard.

A Giants and Dodgers fan, he peppers speeches with baseball references, talking about not promising to hit a home run every time, a veiled reference to campaign promises by Sanders.

Rep Xavier Becerra (D-Los Angeles), chairman of the House Democratic Caucus, campaigns for presidential candidate Hillary Clinton in Las Vegas.

A Clinton staffer drives between stops as his spokesman periodically hands Becerra a single sheet of bullet points he should hit in his next speech, noting examples of how Clinton had been there for the Latino community on immigration and civil rights over the years. The congressman texts throughout the day with his daughter Olivia, a Stanford University material sciences student studying in Florence, Italy, this semester. She wants near constant updates from the trail, he said.

At each stop he speaks about his father, Manuel, a construction worker with a sixth-grade education, and his mother, Maria, an immigrant from Jalisco, Mexico, who became a clerical worker because she couldn’t afford college. He questions if his parents’ success could be possible today.

“Could today’s construction worker married to a clerical worker guarantee four children a college education and buy a house?” Becerra asks a group of Latino voters. “That’s what we’re fighting about.”

Throughout the day, Becerra says Clinton has fought to make that opportunity possible through immigration reform, better wages and the Affordable Care Act.

“She’s been there from the beginning,” he tells the Latino voters. “And at the end of the day, we can all dream, but you’ve got to [be able to] get it done.”

The congressman was not only the first person in his family to go to college, but he graduated with a bachelor of arts in economics and a law degree from Stanford.

He represented mentally ill clients in a legal services office before becoming deputy attorney general with the California Department of Justice. Becerra served one term in the California Assembly before winning a congressional seat with 52.4% of the vote in 1992. He has won each election since with at least 70% of the vote.

He thinks of his father when he gets tired on the trail, Becerra said, and the exhaustion he felt laying cement and pipes and digging ditches with his dad to help pay for college.

“That is work,” he said. “This is fun.”

After a quick turkey sub sandwich and speech at a phone bank center in East Las Vegas, it’s time to find caucus-goers.

Becerra is careful not to tromp through the red gravel lawns of stucco-covered homes in the Sun Country neighborhood. The towering casinos of the strip are just visible 20 miles to the west.

At the dozen or so homes where no one answers, he leaves a handwritten note signed “Xavier” reminding people to caucus for Clinton on Saturday. A dog barks and barks after one doorbell’s buzz.

The temperature rises to 76 degrees. Becerra said it reminds him of his first campaign in 1990.

“We didn’t raise a lot of money,” he said. “But we walked a lot.”

Becerra flips from Spanish to English throughout the day, often giving the same speech in both languages or switching mid-sentence.

“Dime con quién andas y te diré quién eres. Tell me with whom you walk, and I will tell you who you are,” he tells a group of union members wearing purple “SEIU for Hillary” shirts. “I can tell by your T-shirts with whom you walk. We walk with Hillary Clinton, who should be the next president of the United States.”

Becerra modulates his speeches to the audience. He talks about immigration to Latino groups, hard work to labor unions and the water crisis in Flint, Mich., to predominantly black crowds.

He’s careful to spell out the differences between Clinton and Sanders without attacking his colleague too harshly, saying the Vermont senator is making campaign promises he cannot keep, and that Clinton has been involved in Latino issues for much longer. The rhetoric changes based on the crowd -- fiery for Clinton volunteers and more balanced for elected officials or undecided voters.

“If you don’t vote for Hillary this time, that’s OK. I need your vote in November, because at the end of the day, we have to win,“ he tells the audience at a Latino Voter Summit at the College of Southern Nevada.

He knows what it is like to be on the opposing side of the Clintons. Elected in a “change” election year along with Bill Clinton, he worked closely with them over the years. But in 2008, he first was with then-Sen. Christopher Dodd as he tried to win the Democratic presidential nomination. Dodd dropped out before California’s primary, and by then, Becerra was working for Obama, saying he could appeal to all sectors of the American public, helping Clinton’s primary rival develop a strategy to win Latino voters.

In the afternoon, Maria Gray throws open her front door and pulls Becerra into her East Las Vegas home where a handful of friends and neighbors have spent every Saturday for the last six months calling people and urging them to turn out. Tile-roofed homes line the street and Gray’s yard has been turned into an elaborate cactus garden.

Gray, 70, spent six hours knocking on doors for Clinton the previous day. With a broad grin on her face, the tiny Latina barely leaves the congressman’s side in the hour he’s in her home.

Michele Clark, 68, a California native living in Las Vegas, said a Latino running mate would be good for Clinton. She has heard Becerra speak twice and said she’s impressed.

“He would really bridge some big gaps,” Clark said. “He’s really able to engage and connect in ways that a lot of people cannot, and he happens to represent Hispanics and a big state.

A frequent person mentioned to be a Latino vice presidential pick is Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julian Castro. Becerra said it would be a testament to the work Latinos have done for Clinton if she were to select a Latino running mate.

“There are a number of people who are qualified who could be considered,” he said. “I don’t have any problems saying I want to think big. I just am not caught up in saying it has to be a particular position.”

He reverts to analogies about his favorite sport.

“When the game is on, I want to be on the field, but I’m willing to catch, walk, run. I just want to be there,” he said. “I’ll even be water boy.”

Becerra makes a few calls, and supporters hand him the phone when they reach a Spanish speaker. It takes too long to explain who he is, so he soon stops introducing himself as a California congressman.

Gray won’t let Becerra leave without a foil-wrapped plate of chicken wings and cookies. As she reached in for a third “last hug,” she promised to volunteer for him when he needs her. It is only the second time they’ve met.

“For me, it’s an honor to have him in my home,” she said.

Twitter: @sarahdwire

Read more about the 55 members of California’s delegation at latimes.com/politics.

ALSO:

What it’s like when a California congressman campaigns in Nevada

Rep. Xavier Becerra endorses Hillary Clinton: ‘No leader comes better tested’

Top Latino lawmaker has a warning for Trump, other Republicans

Presidential race plays out in Congress: Which candidates does California’s delegation support?

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.