Why Iowa? Small state has outsize role in picking the president

ANKENY, Iowa — In sub-zero temperatures, Iowans will gather Monday in churches, high school gyms and community centers to select the GOP presidential candidate they want to be their standard-bearer in November. Once again, a tiny sliver of the American public — a group smaller than the population of Huntington Beach — will create global headlines about the first presidential nominating contest of the year.

Why does Iowa — an agrarian, elderly, overwhelmingly white state with relatively few residents — play such an outsize role in the presidential race? Especially when California is so much more representative of the nation’s demographics and future?

Such concerns were not front of mind when the modern primary calendar was developed in the late 20th century, said Dan Schnur, a politics professor at USC, Pepperdine and UC Berkeley. He added that while he understands Californians’ frustrations, the state is blessed in many other ways.

“We have Hollywood, and we have Silicon Valley. We have the beaches and the mountains. We have more electoral votes in the general election than any other state in the country,” he said. “Let them have a few weeks in the spotlight.”

Serendipity resulted in Iowa’s crucial place at the head of the political calendar. The Democratic godfather of the event is disappointed his party won’t take part.

By every measure, California’s 39.2 million residents are more representative of the nation’s future than Iowa’s 3.2 million.

Nearly 84% of the Hawkeye state’s residents are non-Latino whites, compared with 59% of Americans and 35% of Californians. Iowa is home to more seniors. California has a far higher median income and is more densely populated.

Even some Iowans agree that there is cause for concern.

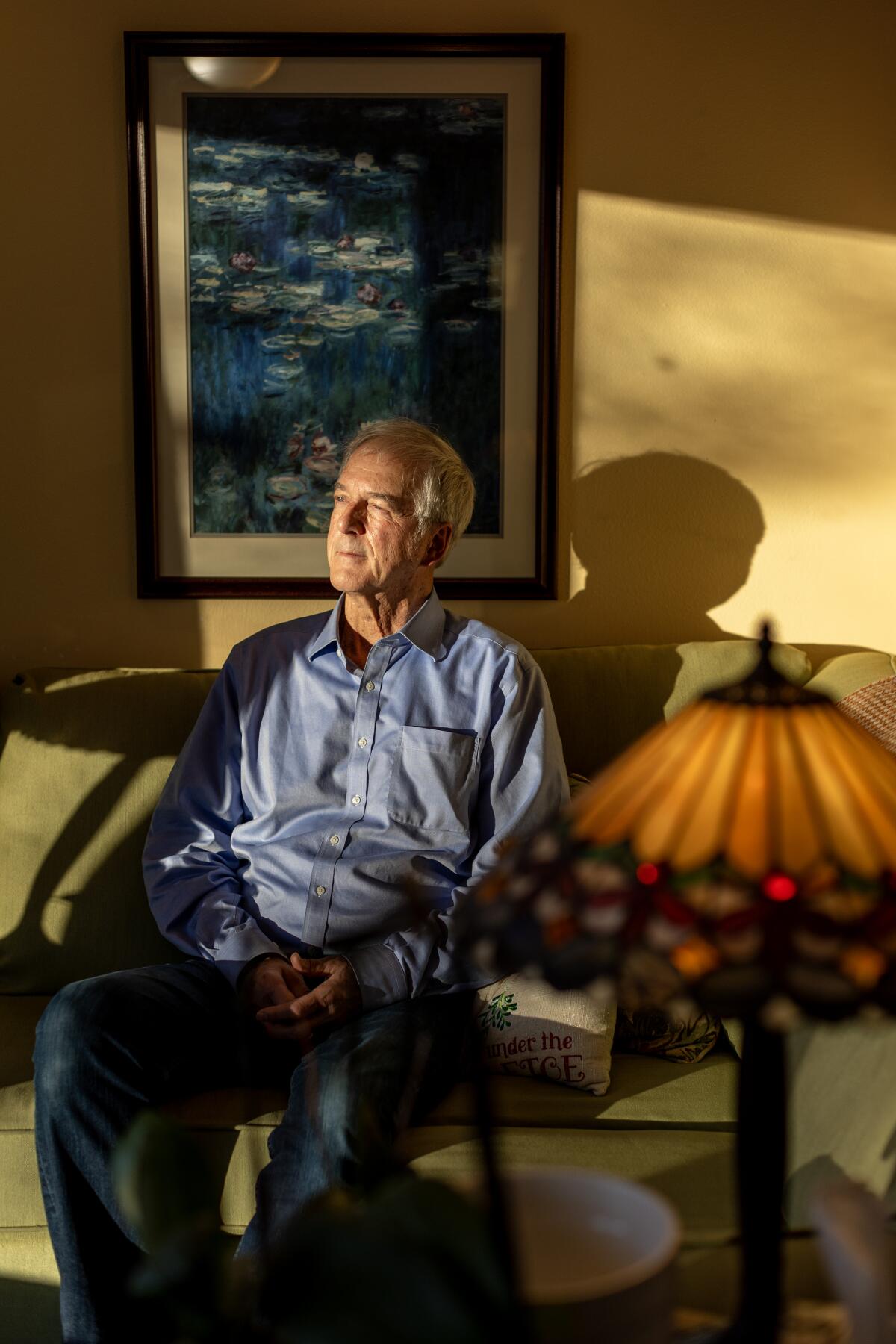

“It’s a real honor for us to have this role,” said retired French teacher Gene Larson, after watching former U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley speak to voters in Ankeny. “I don’t know if I could say we should have it.”

The 71-year-old, who described himself as a centrist who has voted for presidential candidates of both parties, said the nature of the caucuses has changed, as have the demographics of the nation.

“We’re definitely not racially representative of the country — no question there. I do not think it follows that we’re biased,” he said, pointing to then-Sen. Barack Obama’s surprising victory in the 2008 Iowa Democratic caucuses, which laid the foundation for his election to the White House — a moment often highlighted by defenders of Iowa’s role in the nominating process.

That said, it would make sense to overhaul the process, even if it means Iowa loses its status, he noted.

“It would be nice [if] it’s spread around the country. I have also seen the idea of six or eight states being organized in clusters and the different clusters get to go first each year. I think that might be fair,” he said.

“Originally, we prided ourselves on the small-town atmosphere, where candidates had to prove they were people-oriented to succeed. I think that has some merit versus going to a big television state” like California, Larson added. “But I think it’s important to share, and I think maybe it’s time that it be shared around.”

Others argue that while the nominating system is not perfect, it gives an opportunity for Middle Americans to meet and question candidates in a way that would never be possible in California or other large states.

“I don’t know that I can speak to whether or not we’re a perfect cross-section of the country, but I think we have a pretty good representation of conservatives, liberals, Democrats, Republicans — both sides,” said Andrew Stephenson, a manufacturing engineer and undecided voter, after seeing Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis court voters at Jethro’s BBQ in Ames.

“I mean, it has to be somewhere, right?” added the 42-year-old, noting that Iowans have an expectation of meeting candidates and vetting them in person rather than via pricey television ads, the main method of campaigning in large states such as California. “I don’t know who would be better or more appropriate.”

Iowa’s contest became a proving ground for presidential candidates in the 1970s. Other states have questioned Iowa’s outsize role for years but were rebuffed with the argument that any candidate willing to put in the time and effort to meet with Iowans could have a chance there, because of the intimate nature of the caucuses.

Similarly, simmering concerns about the state’s residents not being representative of the nation’s demographics and direction never reached a full boil — until the state’s Democrats so badly flummoxed the 2020 caucus that no formal winner was declared. National Democrats made South Carolina the first official state in their party’s nominating contest this year, though critics say that change had more to do with President Biden’s lackluster showings in Iowa and New Hampshire, which holds the first primary in the nation.

Many Iowa stalwarts argue that the state’s role is justified because it creates an even playing field for candidates, regardless of their financial resources, and because voters expect to be able to query presidential hopefuls.

“Iowans take it very seriously. They really want to get to know the candidates. It’s retail politics,” said Terry Branstad, former President Trump’s ambassador to China and a multi-term governor of Iowa.

He too argued that Obama, with his surprise victory over Hillary Clinton in the 2008 caucuses, would never have become president if the race had started in a large state like California.

“The Clinton money and connections would have dominated, and it wouldn’t have happened,” Branstad said. “That’s the problem in those states — very seldom do people even get to meet the candidates, whereas as in Iowa, a lot of times, they meet them multiple times. So I think that’s important.”

Some Californians agree.

“The case for Iowa is the barrier to entry is low, so it favors any candidate who wants to come in and put in the work,” said GOP strategist Rob Stutzman. “Whereas if you started in a state like California, it would only favor a rich candidate.

“It’s a nation-state. It will always favor the richer candidate,” added Stutzman, who advised former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, as well as billionaire Meg Whitman in her 2010 gubernatorial bid. “It’s too many media markets, it’s too big of a state to move around in efficiently without spending a lot of money on private jets.”

That said, Stutzman finds Iowa’s lack of diversity and agrarian-driven economy “not ideal.” California could be more relevant if it has an early role in the nominating process, as it does this year, when it is among more than a dozen states that will vote March 5, Super Tuesday.

“So there are pros and cons,” he said, before reminiscing about observing prior Iowa caucuses. “It’s a good tradition. Voters there take it seriously. I’ll miss it if it doesn’t happen again.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.