MIAMI — Angelo Gomez walked across seven countries and a gang-infested jungle. He caught a ride through Mexico atop the train known as La Bestia, carrying a bucket of rocks for protection. Then he turned himself over to Border Patrol agents in Texas earlier this month, telling them he feared returning to Venezuela.

Gomez, 30, was the last holdout among his family, having stayed behind to guard their home from squatters in the capital, Caracas, after his parents fled to Peru and his sister journeyed to the U.S. nine months earlier. He had been a street vendor selling anything he could think of — doughnuts, flip-flops, tostones.

But when making enough money to eat became a daily gamble he, too, decided it was time to go.

“If it’s not the colectivos,” he said, referring to Venezuelan armed paramilitary groups, “it’s hunger that will kill you.”

On June 17, Gomez joined his sister at the two-bedroom Miami apartment she shares with nine other family members and friends. Soon after, he learned about a new law set to take effect Saturday that could change everything for immigrants without legal status.

Senate Bill 1718 was signed in May by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a hard-line conservative who has made cracking down on migration a centerpiece of his campaign for the Republican presidential nomination. The broad-reaching law will invalidate driver’s licenses for people who can’t prove their legal status; require hospitals that accept Medicaid to ask patients for their immigration status; make it a felony to transport immigrants without legal status, punishable by up to 15 years in prison; require employers with more than 25 workers to use E-Verify to confirm employment eligibility; and provide $12 million to transport migrants from the border to “sanctuary jurisdictions.”

The law’s implementation follows decisions by DeSantis and Texas Gov. Greg Abbott to transport migrants to California earlier this month, adding Sacramento and Los Angeles to the growing list of major cities led by Democrats that have been targeted by the two Republicans, including New York, Chicago and Denver.

Members of the country’s largest Venezuelan community in Miami have had mixed reactions to DeSantis’ treatment of immigrants.

The number of Venezuelans in the U.S. has nearly tripled in the last decade to 545,000 as of 2021, according to the Migration Policy Institute. In Miami’s conservative-leaning Venezuelan hub, DeSantis’ immigration policies are forcing some longtime residents to reexamine their support for him and newer arrivals to reconsider their future in a state they just started calling home.

Gomez said border agents transported him from Texas to San Diego before releasing him to a church group that drove him and other migrants to a hotel in San Bernardino County. His sister paid to fly him to Miami.

“I told her I should have stayed in California,” he said, partly in jest.

Gomez is anxious about his ability to work. He needs to pay a lawyer to submit an asylum application and wait six months to apply for a work permit that also takes considerable time to process.

He also has to pay back his sister. Gomez said a friend had been offered a ride from the border to New York. Though Gomez considers the migrant transport buses a publicity stunt, he said that if he had gotten the same offer, he would’ve taken it to save money.

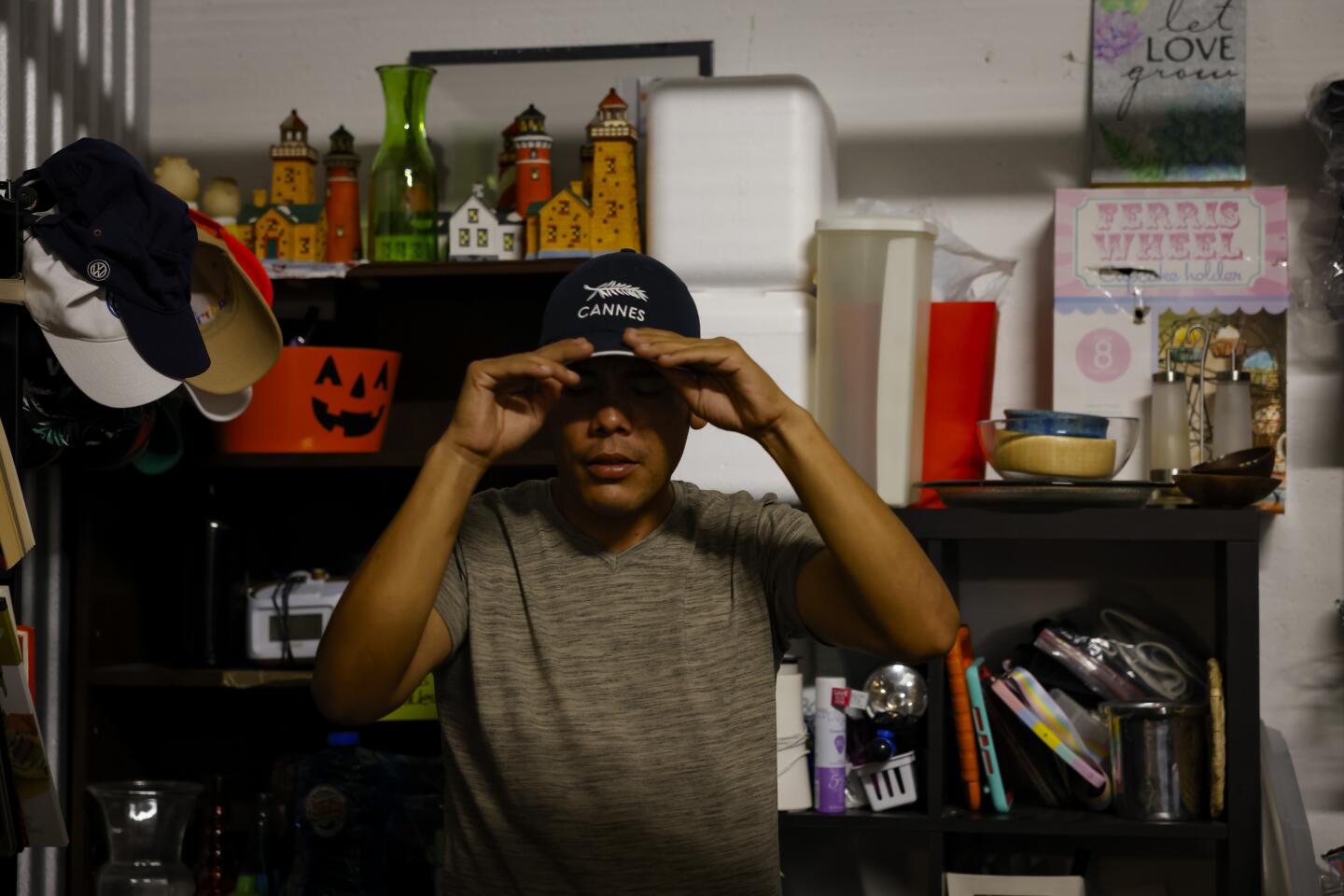

Inside a storage facility in a Doral neighborhood nicknamed “Doralzuela” for its large Venezuelan population, a row of units packed with donations served as a makeshift thrift store. Gomez arrived Saturday afternoon for his appointment there with a nonprofit, Raíces Venezolanas, that helps recently arrived immigrants. Excited about the prospect of finding a job, he picked out a pair of slacks, tennis shoes, a baseball cap and a lunchbox.

But he’s not sure he’ll be in Florida long enough to put them to use.

Gomez’s sister, Angie Suarez, who recently worked picking flowers, said her supervisor told her she couldn’t come back without a work permit. She submitted her application for asylum in March, and it could be early next year before she receives a work permit.

Unsure if she or Gomez can wait that long, they have reached out to friends in Michigan and Atlanta in case they pack up and move again.

“Instead of giving us more tools so that we can all achieve legal status faster, they are cornering us — [as if to say] váyase,” she said of Florida’s government. “Get out.”

Also shopping at the storage facility was Heiddy Tijera, 45, who flew to Miami this month with her husband and 16-year-old daughter after receiving lawful entry through a program that allowed them to apply with a financial sponsor before leaving Venezuela. They reunited with her two adult children who had entered the U.S. at the southern border three months ago.

Tijera said some of her adult children’s friends who were concerned about the new law left the state. Though her children have pending asylum petitions and she has temporary lawful status, she said they are also considering packing up and moving.

She sees SB 1718 and the migrant transports as xenophobic.

“To play with the life of a human being, with those who are vulnerable, speaks more about [the politicians] than of the people who arrive here illegally,” she said. “I recognize that perhaps the migration is disorganized, but they should seek solutions and not more problems.”

But Patricia Andrade, who runs Raíces Venezolanas through her nonprofit Venezuela Awareness Foundation, is a fan of DeSantis. She said that, as a Catholic, she likes his stance on abortion. She also supported his handling of COVID-19, she said.

She doesn’t blame DeSantis for transporting migrants to states with more robust support systems and doesn’t have a problem with the new immigration legislation. Andrade said she believes that being asked to show proof of immigration status is not unlike being asked to show a driver’s license during a traffic stop, and that asylum seekers who were processed at the border have a legal basis to stay and shouldn’t be affected.

“I would like to sit down with him so he can hear why Venezuelans are arriving and rid him of that idea, that bad image he has of immigrants,” Andrade said of DeSantis. “He’s seen what’s happening in Texas. He doesn’t want Florida to be the same.”

It should be the Biden administration’s responsibility to properly vet and care for those who get in, she said.

Andrade said she has visited the border and understands how overwhelmed some towns are. She said she sees the situation through a realistic lens: So long as migrants view the border as being open, those who are fleeing political and economic crises will continue to come.

And as long as they come, she will receive them. Raíces, meaning “roots,” started with one small storage unit in 2016, when Venezuelans first began to flee their country in large numbers. Now more than 7 million have left, a quarter of the country’s population.

Andrade has 18 units filled with donations, each meticulously organized. There’s one stacked with strollers. Another with toys and stuffed animals. A double unit with kitchen items, including an arepa maker. And another space filled with sheets, blankets and towels, all washed by a volunteer, folded and neatly tied with a satin string.

“We try to make sure that when you go home, even if it’s just to sleep on a mattress, that it be with dignity,” she said.

Other immigrant advocates are much less supportive of DeSantis. A rally Saturday drew a few dozen protesters against SB 1718. Before marching through downtown Miami, they prayed for divine intervention, asking God to touch the governor’s heart and revoke the anti-immigrant bill before it could become law.

“No more abuse!” one woman yelled over a loudspeaker, her voice hoarse with intensity. “Liberty for Florida! Respect for immigrants!”

Samuel Vilchez Santiago, Florida director for the American Business Immigration Coalition, views SB 1718 as a measure to advance DeSantis’ presidential ambitions while creating a crisis for Floridians.

Though the law shouldn’t apply to most recently arrived Venezuelans, who have temporary authorization to remain in the country through Temporary Protected Status, parole or pending asylum petitions, Vilchez Santiago said the bill was designed to be vague. He said he worries it will lead to racial profiling as sheriffs across the state who aren’t extensively trained on immigration law attempt to enforce it.

“At the end of the day what they want to accomplish is send a narrative that creates this idea that Florida is not a welcoming place and people shouldn’t come here,” he said of DeSantis’ administration. “But our economy depends on people coming.”

Maria Puerta Riera, a political science professor at Valencia College in Orlando, said transporting migrants to liberal cities may be an effective political play with conservative Latinos. But she said DeSantis’ policies could reflect negatively on him with voters during the general election were he to be the nominee.

“You can’t one day say that you are against socialism and take a photo op with Venezuelans like we see politicians do frequently, and then pass laws that go against the people who are the very victims of those regimes,” said Puerta Riera, who is Venezuelan.

Venezuelans made up just 3% of eligible voters in Florida in 2020. They want politicians who support Venezuela’s plight, Puerta Riera said, but like other Latinos, they also care about the economy and skew socially conservative. Florida’s cost of living is rising, and the Republican Party’s stance on spending, LGBTQ+ rights and abortion attracts many Venezuelans, she said.

Puerta Riera worries that Venezuelan immigrants will fall into the same community divisions as Cubans, who have faced a similar divide among generational, class and racial lines. She has studied the rise of “Magazuelans,” or Venezuelans who have embraced former President Trump.

In observing her own community and monitoring Venezuelan groups on social media, she said she’s starting to notice some make a distinction between immigrants who arrived by plane and those who crossed the southern border. Some Venezuelans speak with contempt of the migrants who have been transported away from the border, she said.

Ernesto Ackerman, who heads the civic group Independent Venezuelan American Citizens, said migrants are better off being transported to cities such as Los Angeles. Because Florida isn’t a sanctuary state, he said, migrants who lack legal status would have a much harder time succeeding there.

But he also pointed to New York City, where migrant arrivals have overwhelmed the city’s shelter system.

“Thank God we aren’t seeing that here in Florida,” he said.

Ackerman moved to the U.S. in 1989 after a wave of protests against the Venezuelan government resulted in hundreds of people killed by security forces. He arrived with a work visa for his medical equipment business and eventually gained citizenship.

He acknowledged it was much easier then to obtain a visa, particularly given his career. But he said the U.S. can’t be the solution to all of Latin America’s problems. And he doesn’t recommend that any Venezuelan travel to the southern border.

“They should stay in Venezuela and try to remove the dictatorship,” he said of the government of President Nicolás Maduro.

Inside a small community center in Hallandale Beach, a congregation rose to sing gospel songs before a Sunday morning sermon.

“There is freedom in the house of God,” sang Juan Carlos Calderon quietly to himself, his hands drawn up to his chin in prayer.

Calderon, associate pastor of the Centro de Esperanza Miami, was among more than 1,000 evangelical pastors who signed a letter last month pleading with DeSantis to veto SB 1718, saying it will incite fear and create barriers between churches and the communities they serve.

Though he believes in controlled immigration, he said the new law is drastic and irrational. State leaders should pressure the Biden administration to take charge of the issue rather than sanction their own residents, he added.

Calderon came to the U.S. from Venezuela with his wife and two children in 2016, leaving behind nearly all of their personal belongings, as well as two dogs and three cats. Seven years later, they’re still awaiting a decision in their asylum case, but have work permits and driver’s licenses.

On Sunday, lead pastor Ronald Torres, who is also from Venezuela, preached about how Jesus changed the world through love and justice.

“The word [of God] says to help your neighbor as you help yourself,” he said.

A few months ago, Torres said, he performed one such neighborly deed. After a church service, he went outside to the park and met a Venezuelan family with two young children who had just arrived from the border. Homeless and hungry, they asked for help and Torres connected them with a food bank and other services. He worries the new immigration law could result in sanctions for giving migrants rides to food banks or even church services.

Calderon, who otherwise supports DeSantis, called SB 1718 his first mistake as governor. On a yearly trip to Tallahassee, Calderon and other church leaders requested an amendment to the bill that would have excluded churches from being sanctioned under the law. They weren’t successful.

“Compassion cannot be a crime,” he said. “Do you need papers to speak with Christ?”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.