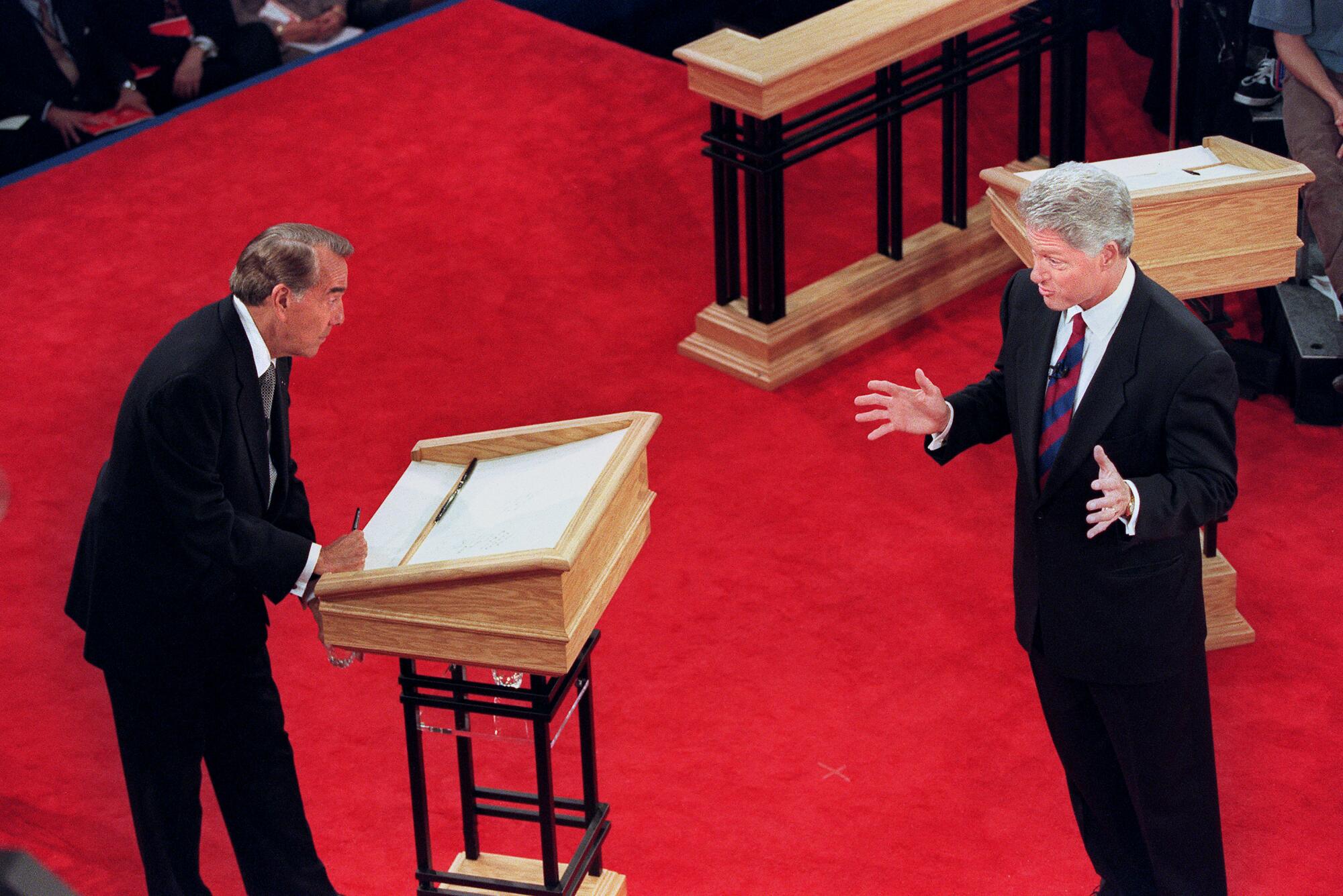

Bill Clinton was busy filling Cabinet positions and shaping his economic agenda when a memo landed from a team of political advisors. Although Clinton was still more than a month away from becoming president, the topic was his reelection nearly four years off.

Marked confidential and spilling over nearly eight pages, the document outlined a strategy considered vital to Clinton’s hopes for a second term: Lock down California and its generous share of electoral votes so his campaign could “concentrate its energy on other, more tightly contested, states.”

In 1992, Arkansas’ five-term governor became the first Democratic presidential candidate in nearly three decades to carry California, the political birthplace of Richard M. Nixon and Ronald Reagan. Few, if any, considered Clinton’s victory in California the start of a political realignment; he won just 46% of the vote.

But his victory and a repeat in 1996 — the product of relentless courtship and a fire hose of federal spending — helped color California a lasting shade of blue and dramatically reshaped the fight for the White House.

For much of its history, the West was Republican ground. Today, it’s a bastion of Democratic support, a shift that has transformed presidential politics nationwide. Mark Z. Barabak explores the forces that remade the political map in a series of columns called “The New West.”

It augured a major partisan shift throughout the West, which over the last 20 years has become a Democratic stronghold, stretching from the Pacific Coast, across the desert Southwest into the Rocky Mountains.

That political base has freed Democrats to compete in the battlegrounds of the Midwest and reach for states like Georgia, North Carolina and Virginia that were once well beyond the party’s grasp.

In this series, called “The New West,” I’m exploring the reasons — economic, demographic, political — for that change.

In California, there were several factors.

Among them, the polarizing politics of the state’s Republican governor, Pete Wilson, which helped activate the state’s rapidly growing Latino population and turn those voters against the GOP. The rightward drift of national Republicans, especially on issues like guns and abortion. An economy that scraped bottom under President George H.W. Bush, then bounced back strongly under Clinton.

Democrats drawn by Oregon’s tech jobs and nature have made the state solidly blue. It’s part of a transformation that remade the West and recast the fight for the White House.

But the transformation was also the result of a purposeful White House effort to remake California and turn the historically Republican-leaning state into a blue bulwark for decades to come.

California Democrats — a continent away from the East Coast power axes — were used to being ignored by party leaders, except when it came time to extract deposits from the state’s rich vein of campaign cash.

“They felt no one cared,” said Bob Mulholland, who spent decades as a California Democratic Party strategist.

That changed the instant Clinton took office.

“All of a sudden, everywhere I went people would say, ‘I just got a call from the White House,’ ‘I just got a letter from the White House,’” said Mulholland, who flew to Washington to witness Clinton’s swearing-in as president.

“There was never a day after that he forgot about California.”

Before Clinton, the last Democratic presidential candidate to carry the state was Lyndon Johnson, who won California as part of his 1964 landslide. At the time, Clinton was a gregarious 18-year-old college student who collected friends the way others gather wildflowers.

One of them was Derek Shearer, a native Californian whom Clinton met years later as a Rhodes scholar at Oxford University. Shearer, a freelance journalist at the time, went on to teach at Occidental College in Los Angeles and served as Clinton’s host and guide during regular California visits.

Clinton loved the state: the sun, the lifestyle, the possibility.

In the late 1970s, he became friendly with Mickey Kantor, a Los Angeles attorney and Democratic Party powerhouse who knew Clinton’s wife, Hillary, through their work with the Legal Services Corp. during the Carter administration.

By the time Clinton ran for president in 1992, he’d built an extensive network of California connections — in politics, business, Hollywood — thanks in good part to the doors opened by Shearer, Kantor and two fellow Arkansans, Harry Thomason and his wife, Linda Bloodworth-Thomason, who’d moved to California to pursue a career in television production.

Kantor became the national chairman of Clinton’s campaign and was among those seeing political opportunity in the state, despite its history of favoring Republicans. In 1988, Bush — Reagan’s vice president — defeated Democrat Michael Dukakis, by a less-than-overwhelming 51% to 48%.

Since then, the economy had nosedived and Bush had alienated several key California constituencies, among them Black and Latino voters, environmentalists and backers of abortion rights.

Moreover, while Clinton showed a natural ease with California and its clamorous culture, Bush never seemed to get a grip on the state. Raised in Connecticut and rooted in Texas, the patrician Bush came across as a hapless tourist squinting to understand the dialect and comprehend the natives.

His California campaign was startlingly inept.

The day Bush endorsed creation of a marine sanctuary protecting a quarter of the state’s coastline he opted not for a camera-ready appearance by the sea — waves crashing, seals barking — but a stop at a refinery with an oil tanker as the television backdrop. The landmark decision was offhandedly announced in a standard-issue press release.

Still, Clinton needed help carrying the state in 1992. He benefited from the presence of Ross Perot, the feisty third-party candidate who spent most of his time attacking Bush. He got a lift from the buzz surrounding two groundbreaking Democratic women, Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer, running for separate U.S. Senate seats.

Above all, Clinton capitalized on the sour mood of Californians amid the worst economic downturn since World War II, which followed the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of a decades-long arms race that fueled the state’s robust defense and aerospace industries.

His victory and an end to Democrats’ prolonged political drought was, however, only a start.

“It will continue to be important to communicate your connection with this state and your concern for its problems,” a team of California strategists — Rick Allen and Los Angeles attorneys Kim and Bill Wardlaw — wrote in their confidential strategy memo as Clinton prepared to enter the White House. “Californians are looking to you to improve conditions,” especially the economy.

Failing that, they warned, “the volatile California electorate is likely to swing back to the Republicans.”

On Jan. 17, 1994, at 4:31 a.m., a violent shudder tore through Southern California.

The Northridge earthquake, with a magnitude of 6.7, killed about 60 people and damaged or destroyed more than 80,000 structures.

President Clinton arrived days later.

“We have a national responsibility” to help lead the recovery, Clinton said after gazing at a collapsed section of the 118 Freeway in Simi Valley. But Clinton did more than visit. He announced millions of dollars in immediate assistance and promised more to come. “This is something we intend to stay with,” he vowed, “until the job is over.”

It was a formula Clinton followed throughout his presidency: Lavish time, money and attention on California.

Then make sure everybody knew it.

“We didn’t just step up on disaster relief,” said John Emerson, who ran Clinton’s 1992 campaign in the state and helped stock his administration as deputy personnel director. “There was a concerted effort to be present and visible every step of the way.”

Hundreds of Californians served under Clinton. Among them Secretary of State Warren Christopher; budget director and later White House chief of staff Leon Panetta; press secretary Dee Dee Myers and chief economic advisor Laura D’Andrea Tyson.

Kantor joined the administration as U.S. trade representative and became commerce secretary when a plane crash killed his predecessor, Ron Brown, who’d been tasked with overseeing the state’s economic recovery. Tom Epstein, a veteran of numerous California campaigns, was installed in the White House to mind the political needs of folks back home.

After years of feeling overlooked, it was reassuring — and exceedingly helpful — for business leaders and government officials to call Washington knowing someone from the state would be on the other end of the line.

Some random bureaucrat “might have no idea who Michael Ovitz is, or understand the importance of UCLA to the local economy,” said Emerson, a former chief deputy L.A. city attorney whom Clinton called his “secretary of California.”

“I knew Michael Ovitz,” Emerson said of the onetime Hollywood super agent. “He picks up the phone and says there’s a problem with the UCLA hospital system and getting [Federal Emergency Management Agency] money, I’m going to be responsive.”

Once solidly Republican, the West has become political bedrock for Democrats. No state has changed as emphatically in the last two decades as Colorado.

Other states could only envy California, as the federal spigots opened up.

Billions in earthquake relief. Billions in military spending. Billions to help the defense industry retool.

Money for a transit link between the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles. Money to convert a former Army base into Cal State Monterey Bay. Money to treat sewage from Mexico and clean up San Diego’s beaches.

Kantor personally negotiated a trade provision opening the Japanese market to California-grown rice. The tech industry benefited from relaxed controls on exporting supercomputer equipment.

And on.

Panetta, who represented a large swath of coastal California in Congress before joining the Clinton administration, offers no apology.

“A lot of states are trying to figure out how they can get crumbs off the table,” he said, looking back at the assiduous care and feeding of California. “But I think they also understood the politics of what [Clinton] was doing. He was trying to make sure California, because it was important to his reelection, was having its needs met.”

But it was not strictly about politics.

At the time, Clinton wrote in his autobiography, Southern California constituted the world’s sixth-largest economy. So helping resuscitate the region was vital to the nation’s overall recovery.

In all, Clinton visited California 56 times from 1993, the year he assumed the presidency, through 2001, the year he left the White House, according to a tally kept by his presidential library. That is far more than any other state, save Maryland, home to the presidential retreat at Camp David, and New York, where Clinton settled after leaving Washington.

The effort paid off handsomely.

Clinton easily carried California on his way to winning his second term in an electoral college landslide. By the time he left the White House, the state had become a Democratic fortress.

In 2000, Clinton’s vice president, Al Gore, carried California by 12 percentage points. Since then, no Democratic presidential candidate has won by less than double digits.

Republicans long ago quit trying to compete.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.