Column: Debt ceiling negotiations were hard when Biden was vice president. They’re even harder now

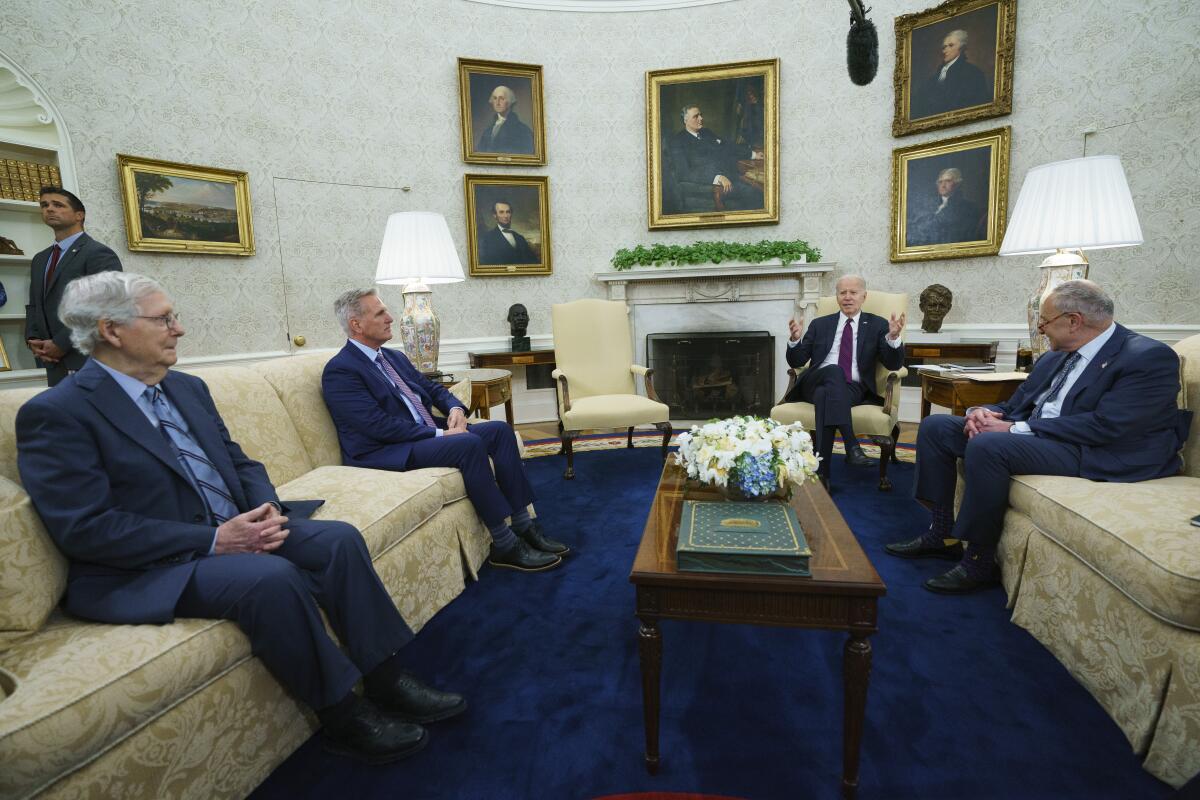

WASHINGTON — For a brief moment last week, it was possible to imagine that President Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) had found a patch of common ground in their standoff over the federal debt ceiling.

“We’re going to come together, because there’s no alternative,” Biden predicted.

“It’s not that difficult to get to an agreement,” McCarthy ventured.

But by Friday, their differences didn’t seem so easy to bridge.

McCarthy’s chief negotiator briefly suspended talks, saying Biden’s aides weren’t being “reasonable.”

“We’ve decided to press ‘Pause,’ because it’s just not productive,” Rep. Garret Graves (R-La.) told reporters.

The White House issued a tart statement accusing Republicans of “recycling a barely watered down version of their extreme budget proposal.”

The financial markets, which had risen on hopes for an early agreement, headed downward.

So much for irrational optimism.

The talks must now sputter on in that unpromising spirit — toward the brink of an unprecedented federal default, and perhaps beyond.

Despite the angry deadlock, it has never been impossible to discern where a middle-ground solution to the fight over federal spending might lie.

Republicans are demanding deep cuts in spending on domestic programs, new work requirements on federal benefits for poor people, lighter regulation of oil and gas drilling, and the repeal of Biden’s ambitious green energy program.

Biden and his aides agreed to negotiate over most of those items, at least around the edges.

New analysis of midterm voting records highlights the key role that young voters played, delivering hotly contested races for the Senate and governorships to Democrats. Can Biden count on them again in 2024?

But the two sides remained far apart on the core issue of federal spending. McCarthy wanted to cut domestic spending by $100 billion next year, then hold growth below the rate of inflation for the next 10 years. Democrats said cuts that deep would slash domestic programs by 22% or more, which didn’t seem reasonable to them.

The answer isn’t as simple as splitting the difference. Politics get in the way.

The hard-line House Freedom Caucus says it considers the GOP demands nonnegotiable, and has urged McCarthy to refuse to make any concession. The speaker needs the Freedom Caucus’ support to keep his job, and his ability to deliver votes for a compromise no one will love is untested.

Biden is a surer bet on that score. He has navigated his party’s internal debates for half a century, including in similar debt ceiling negotiations in 2011 and 2013.

But he, too, faces incipient rebellion. Progressive Democrats have threatened to revolt if the president agrees to impose new work requirements on benefit programs such as Medicaid or food stamps.

Like the Freedom Caucus, many of the progressives say they don’t think their side should be negotiating at all.

The president initially agreed with them. He said he wouldn’t bargain over raising the debt ceiling to pay the federal government’s bills, and accused Republicans of taking the economy hostage. But after several weeks, he blinked and agreed to negotiate.

As a practical matter, he had little choice: He’s running for reelection. Voters tend to blame the incumbent president for a weak economy whether he deserves it or not. If the debt ceiling imbroglio nudges the economy into recession, Biden’s chances of keeping his job will plummet.

It didn’t escape the notice of White House aides when former President Trump, who hopes to face Biden in next year’s election, urged his supporters in Congress to embrace the risk of a default.

“Republicans should not make a deal on the debt ceiling unless they get everything they want,” he said in a social media post. “Do not fold!”

Meanwhile, Biden’s charge of GOP hostage-taking didn’t appear to sway public opinion much.

Polls show that most voters fear the consequences of a default, but that they also agree with Republicans that the debt ceiling should be used to rein in federal spending.

A rematch between the president and his predecessor wouldn’t simply be a rerun of 2020, but a referendum on both of their records — and a test of which one voters like less.

As for which side deserves blame for the impasse, many voters point at both parties. There’s no evidence that Republicans are paying a significant price for hostage taking.

Nevertheless, both parties are already accusing the other of responsibility for potential calamity. One side has taken to calling it a “Biden default,” the other a “Republican default.”

Even if Biden and McCarthy strike a compromise, it seems unlikely that both houses of Congress will approve it without drama or delay.

The Treasury says the government could run out of money by June 1, a little more than a week away. Goldman Sachs says the real deadline is probably closer to June 8, just a week later.

Biden says he’s still optimistic.

“I still believe we’ll be able to avoid a default and get something decent done,” he said Saturday in Tokyo before heading back to Washington for last-minute negotiations.

That’s how fiscal standoffs got solved in 2011 and 2013, when then-Vice President Biden made deals with Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell. What we don’t know is whether those old rules still apply in the more polarized Washington of 2023.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.