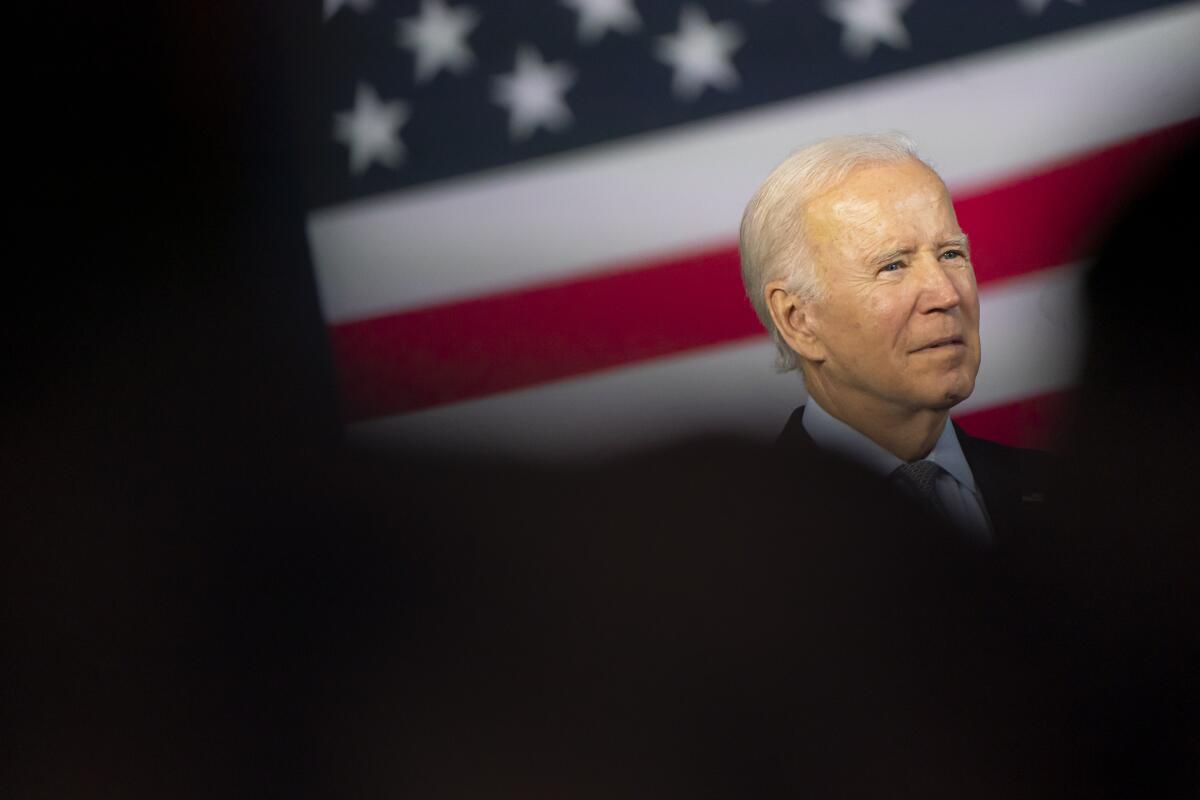

Biden returns to world stage after midterm election

A stunning Democratic performance in Tuesday’s midterm elections lent unexpected momentum to President Biden as he prepared to shift his attention abroad this week, reminding America’s allies and rivals that he’s still the president despite uncertainty about whether his legislative agenda will survive a potentially split Congress next year.

Before all the ballots are counted, Biden will set off Thursday on a seven-day diplomatic tour of Egypt, Cambodia and Indonesia to attend four global summits and navigate an array of consequential foreign policy priorities.

Biden will probably begin his foreign trip in a strengthened position. His party has already outpaced historical precedents and preelection expectations, vindicating a president who’s struggled with low approval ratings and voter concerns over high inflation.

“While the press and the pundits were predicting a giant red wave, it didn’t happen,” Biden said in remarks at the White House on Wednesday.

But control of Congress — and with it the fate of Biden’s agenda — was still unclear Thursday, with races in the House of Representatives still undecided and Senate seats in Arizona and Nevada too close to call. A runoff election for a Senate seat in Georgia is scheduled for next month. If Democrats ultimately lose their majorities in the House or the Senate, the result could weaken Biden’s hand with foreign leaders as he grapples with diplomatic challenges on climate change, Ukraine and China.

“The president will ask countries to make difficult choices — whether that’s advancing climate goals or shifting supply chains away from their reliance on Chinese companies,” said Kori Schake, a foreign policy expert at the American Enterprise Institute who served on President George W. Bush’s National Security Council. “That will be much more difficult to persuade other countries ... if people have doubts whether President Biden can persuade the United States Congress to do hard things.”

Biden’s itinerary includes a short stop Friday in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, where he’ll attend the United Nations climate conference to assert American credibility on climate change. He will then travel to Phnom Penh, Cambodia, to attend the Assn. of Southeast Asian Nations summit before arriving in Bali, Indonesia, for the Group of 20 summit, an annual gathering of leaders from the world’s largest economies.

The high-profile event puts Biden in the same room as Chinese President Xi Jinping, who tightened his grip on power after securing a third term as China’s Communist Party leader in October. The two presidents will meet Monday ahead of the G-20 for their first face-to-face conversation since Biden took office.Russian President Vladimir Putin, whose forces invaded Ukraine more than eight months ago, is now expected to skip the summit.

Past presidents have also pivoted to foreign policy in the wake of midterm elections. President Obama took a similar 10-day trip to the region to attend a suite of Asian-focused summits in 2010, when Democrats lost 63 House seats and the party’s control of the chamber. Three days after Republicans lost their House majority in the 2018 midterms, President Trump flew to France to mark the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I.

President Clinton, who oversaw the loss of Democratic control of Congress in 1994, made his mark on foreign policy by brokering peace in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Northern Ireland and aiding the expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Though Biden returns to the international stage while at risk of losing control of the House, he pointed out that his party lost fewer seats in the chamber “than any Democratic president’s first midterm election in the last 40 years.”

Since 1934, the president’s party has lost an average of 28 House seats and four Senate seats in all midterm elections, according to the American Presidency Project at UC Santa Barbara.

“The world stage is a great place for the president to turn because that’s an area where he has more control than when dealing with domestic policy, where he needs Congress to pass stuff,” said Tevi Troy, a presidential historian and head of the presidential leadership initiative at the Bipartisan Policy Center. “It’s a good pivot for a president.”

But even Biden’s crowning foreign policy achievement — reinvigorating the NATO alliance in the wake of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine — is under threat as House Republicans raise the idea of cutting off foreign aid to Kyiv should they take control of the House next year. Part of Biden’s challenge will be convincing European allies to continue support for Ukraine amid a deepening energy crisis and shortage of food, exacerbated by high inflation.

Questions of whether Biden can work with a potentially divided Congress may undercut his pitch on American leadership on Ukraine and other priorities such as climate change. The president, who campaigned on his ability to work across the aisle and has signed into law a series of bipartisan bills, closed out the campaign by excoriating Republicans who he said put democracy in jeopardy.

“I’m prepared to work with my Republican colleagues,” Biden said at the White House. “The American people have made clear, I think, that they expect Republicans to be prepared to work with me as well.”

Republicans have signaled plans to try to repeal parts of Biden’s landmark Inflation Reduction Act if they regain control of Congress. The law includes a nearly $400-billion investment in clean energy subsidies and represents the United States’ most serious effort yet to combat climate change.

The president made clear he wanted to continue bipartisan support for Ukraine while also warning he refused to walk away from “historic commitments we just made to tackle the climate crisis.”

But the months before new members of Congress take office in January are likely to mirror a similar period the Obama administration endured following the 2010 midterms, when Republicans refused to raise the federal debt limit unless Obama agreed to spending cuts. Biden will have to work with GOP lawmakers to pass routine legislation to fund the government and raise the national borrowing limit by early next year.

Some within the Democratic Party feared Biden’s closing message on threats to democracy appeared out of touch with voters’ concerns about inflation and the direction of the economy.

But exit polls showed that although inflation was a top voter concern, the future of democracy came in a close second, according to an Associated Press survey of more than 94,000 voters conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago, a nonpartisan research group. Abortion rights also appeared to be a priority for many voters.

Should Biden face a GOP-led House next year — and with it an expected flurry of investigations into his administration — the contrast could benefit his campaign if he chooses to run for reelection, said Ben LaBolt, a former Obama administration spokesman who remains close to the Biden White House. Similar dynamics in 1994 and 2010, LaBolt said, helped both Clinton and Obama secure a second term.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.