In Georgia’s pivotal Senate race, Herschel Walker tests Republicans

ALPHARETTA, Ga. — Lifelong Republican Joanne Eaton faced a predicament this week as she went to the polls: She wanted the GOP to gain control of the U.S. Senate, but wasn’t sure she could cast a ballot for Herschel Walker, her party’s embattled candidate in Georgia.

“I’m kind of undecided,” the 64-year-old retired stay-at-home mom said of the former football star as she stood outside a polling station Monday in this affluent Atlanta suburb, a former Republican stronghold that in recent years has shifted blue. “His whole history, his background. The violence, the mental health issues. The things he’s lied about…”

After voting for Donald Trump in 2016 then Joe Biden in 2020, Eaton said she leaned toward “voting for the people, not the party.” She had no qualms about voting for Republican Gov. Brian Kemp, who satisfied her with his handling of COVID-19. But Walker, she said with a nervous laugh, “I just don’t know.”

Herschel Walker is one of the Republicans’ most problematic politicians. The Heisman Trophy-winning University of Georgia running back and multimillionaire businessman who has described himself as “not that smart” is testing the power of the country’s political tribalism. In an age of deep partisanship, can an “R” beside Walker’s name help him overcome his history of false and inflated claims, unpredictable behavior and alleged threats of violence?

For months, Democrats had hoped Walker’s propensity for gaffes and lies would block Republicans from reclaiming this battleground seat and seizing control of the Senate. But now they are worried he might win.

“The state where we’re going downhill is Georgia,” Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) was caught saying on a hot mic to President Biden on Thursday. “It’s hard to believe that they will go for Herschel Walker.”

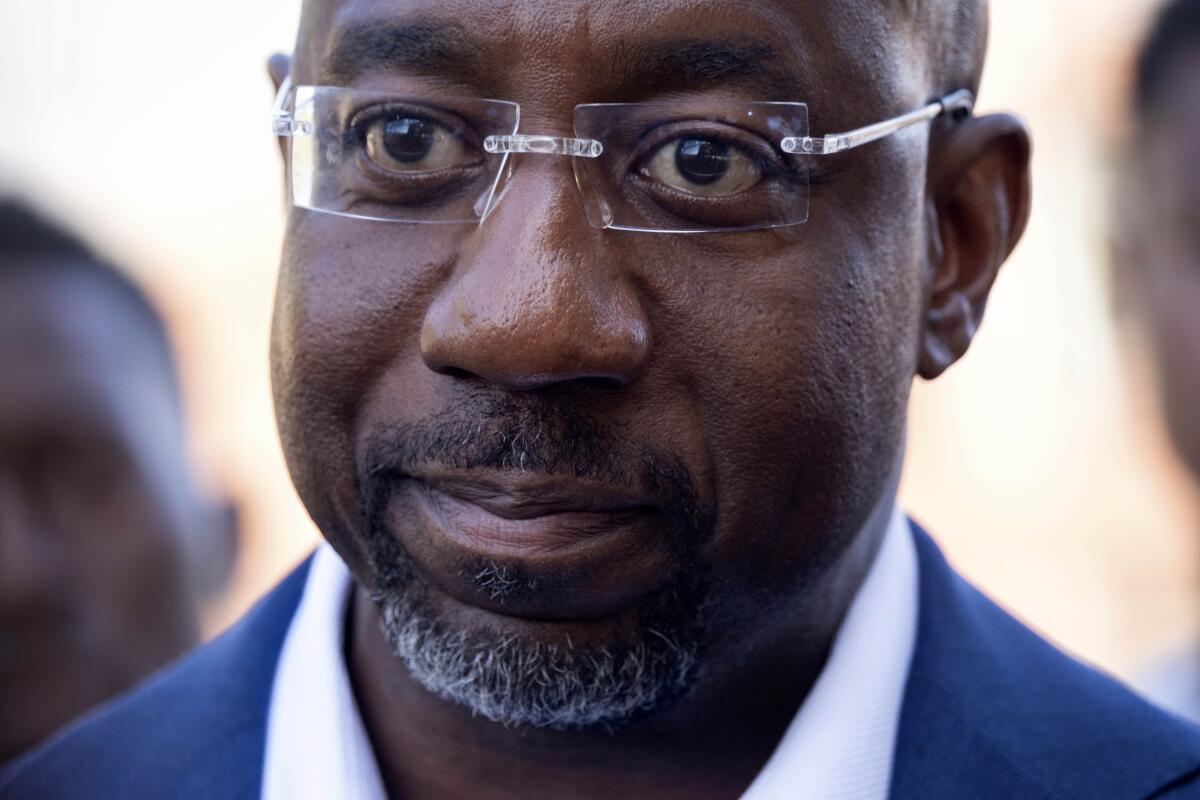

Since he entered the Senate race against Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock, senior pastor at Martin Luther King Jr.’s former church, Ebenezer Baptist, Walker has been embroiled in controversies. The celebrity athlete and Trump protege has exaggerated his financial success, falsely claimed he worked for law enforcement and bragged that he was “in the top 1%” of his college graduating class — despite the fact that he did not graduate.

This summer, the Daily Beast revealed that Walker, who has criticized absentee fathers, had two sons and a daughter he had not publicly acknowledged. Democratic attack ads have featured his ex-wife’s allegations that he pointed a gun at her head and threatened to kill her. In early October, an ex-girlfriend accused Walker, who has said he supports a national ban on abortion, of paying for her 2009 abortion and pressuring her to get another two years later. Walker denied the claim.

On Wednesday, a second woman came forward, saying Walker encouraged her to terminate her pregnancy in the 1990s and drove her to a clinic in Dallas for an abortion. Walker denied the latest allegation at a campaign event, adding, “I didn’t kill JFK, either.”

With less than two weeks until election day, an average of recent polls shows Walker trailing Warnock by just 1.7 percentage points. Polling for the Georgia governor’s race has incumbent Republican Brian Kemp leading Democrat Stacey Abrams by 6.7 points.

The vast majority of Georgia Republicans appear to be sticking with Walker. But a small but significant section of more moderate voters are considering splitting their ticket, voting for Kemp but not Walker, experts say.

“For a lot of white, college-educated voters who probably still think of themselves as Republicans, the question is how many of them come to the conclusion that, yes, they’re Republicans and they’re going to vote Republican for the rest of the ticket, but they just can’t bring themselves to vote for Herschel Walker,” said Charles Bullock, a political science professor at the University of Georgia.

In the November midterm election, California is one of the battlefields as Democrats and Republicans fight over control of Congress.

It’s a dilemma many of those voters faced in 2020, when enough Republicans and Republican-leaning independents here rejected Trump to help usher Biden into the White House, Bullock said. Two months later, the GOP suffered further losses when Warnock and Jon Ossoff narrowly won special election runoffs that secured Democrats’ Senate majority.

The pattern of many voters considering splitting their ticket extends to battleground states beyond Georgia. In Ohio, Republican Gov. Mike DeWine seems to be cruising to reelection over Democrat Nan Whaley, while the Senate race between Trump-endorsed Republican J.D. Vance and Democratic Rep. Tim Ryan is too close to call, according to polls.

Blake Masters, with his provocative statements and problematic positions, throws a lifeline to Democratic rival Mark Kelly.

In Arizona, Democratic Sen. Mark Kelly has held a steady lead over Trump acolyte Blake Masters even as the gubernatorial race between Democrat Katie Hobbs and Republican Kari Lake looks to be a toss-up. And in the Pennsylvania governor’s race, Democratic Atty. Gen. Josh Shapiro holds a commanding lead in polls over election-denying Republican Doug Mastriano, while the Senate race between Democratic Lt. Gov. John Fetterman and Republican TV personality Dr. Mehmet Oz appears close.

At a polling station in Alpharetta, the majority of voters appeared to be casting their ballots along partisan lines.

Swati Joshi, the 49-year-old owner of a global communications firm, said she didn’t know much about Walker beyond what she had read in the media. She couldn’t fathom how anyone could vote for him.

“He sounds dumber than a box of rocks,” the independent voter said before casting her ballot for Warnock and a full slate of Democratic candidates. “I think he’s just a puppet for Trump.”

Many Republicans brushed off talk of Walker’s mistakes, saying they were in the past.

“He’s gotten into the church now, so he’s a very different person,” said Mary Maziarka, a retired office and retail worker from Milton, Ga.

Republican after Republican, and some independents, said they were voting for Walker because they blamed Democratic policy in Washington for inflation.

An executive with four kids said his budget has been hit so hard he was shopping at Aldi instead of Whole Foods. A boat mechanic said he had loaded his freezer with game. A retired graphic designer on a fixed income said he could no longer afford to buy snacks for his grandkids.

With Democrats controlling the White House and Congress and playing defense on the economy, many Republican leaders and strategists are increasingly confident their party has momentum.

“The issues in Washington are so bad from our perspective that it’s still a no-brainer for most Republicans to vote for Herschel Walker,” said Kasey Carpenter, a Republican state representative from Dalton, a small city about 85 miles northwest of Atlanta. Many Republicans were wary of Walker’s baggage, he said, but they were more incensed about inflation, the student loan buyout and the $1.3-trillion federal deficit.

With the midterm election looming, these California voters fear U.S. democracy is beyond repair, and blame politicians for feeding the dysfunction.

“They’re holding their nose and voting for Herschel,” Carpenter said. “Taking back the Senate far outweighs the drama of the election.”

While Walker initially alienated many suburban conservative voters, Republican strategists said his performance in his only debate with Warnock, which he passed Oct. 14 without major gaffes, made some consider him a safer bet.

Some of Walker’s bizarre comments — blasting Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, which includes provisions to fight climate change, by asking a crowd, “Don’t we have enough trees around here?” or saying that people worried about high insulin costs “gotta eat right” — are mocked by critics. But Brian Robinson, a Georgia GOP strategist who served as former Gov. Nathan Deal’s deputy chief of staff, said they can make the candidate relatable to ordinary voters. Even brandishing an honorary badge — when confronted with his false claims of working for law enforcement — resonated with his core constituency because he was showing his support for police, Robinson said.

For years, Georgia Republicans focused on their traditional base as the state became more diverse and more purple. But in this campaign cycle, Robinson said, Republican candidates have reached beyond rural and exurban counties to suburban and minority voters. In Atlanta’s northern suburbs, Robinson said, Republican campaign placards were cropping up in neighborhoods where they had disappeared in 2020.

“A lot of white metropolitan voters are coming back home,” he said. “They’re disillusioned with the results of Democratic policies, not crazy about Biden.”

Fredrick Hicks, a Democratic political strategist based in Atlanta, said Democrats were focused on getting younger and more diverse people to the polls and trying to defuse anti-Warnock sentiment among soft Republican voters so they skip the Senate race.

“All Warnock really needs is 40,000 people who would have voted for Walker to stay home,” Hicks said.

In a race in which Democrats have outspent Republicans on campaign ads by $130 million to $113 million, both sides are targeting swing voters. Two weeks ago, Warnock ran an ad featuring Republicans and independents who said there is “no way” they can vote for Walker.

Republicans have tried to tarnish Warnock’s reputation, with a pro-Walker political action committee airing a TV ad that features 2020 police body-camera video of Warnock’s ex-wife calling him a “great actor” to investigators after he denied her claim that he ran over her foot with his car during an argument.

In another ad, Walker accused Warnock of running a “nasty, dishonest campaign” and cast himself as being upfront about his past problems, including his diagnosis with dissociative identity disorder, in his 2008 memoir, “Breaking Free.”

“As everyone knows, I had a real battle with mental health, even wrote a book about it, and by the grace of God, I’ve overcome it,” Walker said.

Last week, Warnock responded with a pair of negative ads, accusing Walker of “lying” about being transparent in his memoir, which does not mention that he threatened his ex-wife. The Democrat also broke his silence on the allegations that Walker paid for an ex-girlfriend’s abortion, calling Walker a “hypocrite.”

As Democrats target soft Republican voters, Republicans have run radio ads and sent out mailers targeting Black men by saying Biden and Warnock want to let boys play girls’ sports.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“It’s a game of chess — move and countermove,” Hicks said. “Democrats are just now starting to wake up to the importance of the Black male vote. In the last few weeks, few months maybe at most, they have started to realize that this is a valuable voting bloc, and it’s probably a function of looking at Republicans going after that bloc and saying, ‘Oh, we’ve got to secure this group.’”

Jason Shepherd, assistant professor of political science at Kennesaw State University and former chair of the GOP in Cobb County, Ga., said the race was still “extremely tight.” But Republicans were less worried now about a mass wave of split-ticket voters in the suburbs.

Walker doesn’t need to get all the voters considering a split ticket, Robinson said. “He just needs to get some of them.”

Ultimately, Joanne Eaton did not end up casting her vote early last week in Alpharetta because the line was too long. But a day later, upon reflection, she said, she was 99% sure she would cross a box for Walker despite her reservations about his character.

“I’m pretty much resigned to the fact that I’ll vote straight Republican,” she said. “I just think we need to have more Republicans to take the Senate and the House.”

Times staff writer Mark Z. Barabak contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.