WASHINGTON — For a brief time in 2020, it seemed as though the vote-by-mail movement was having a bipartisan moment.

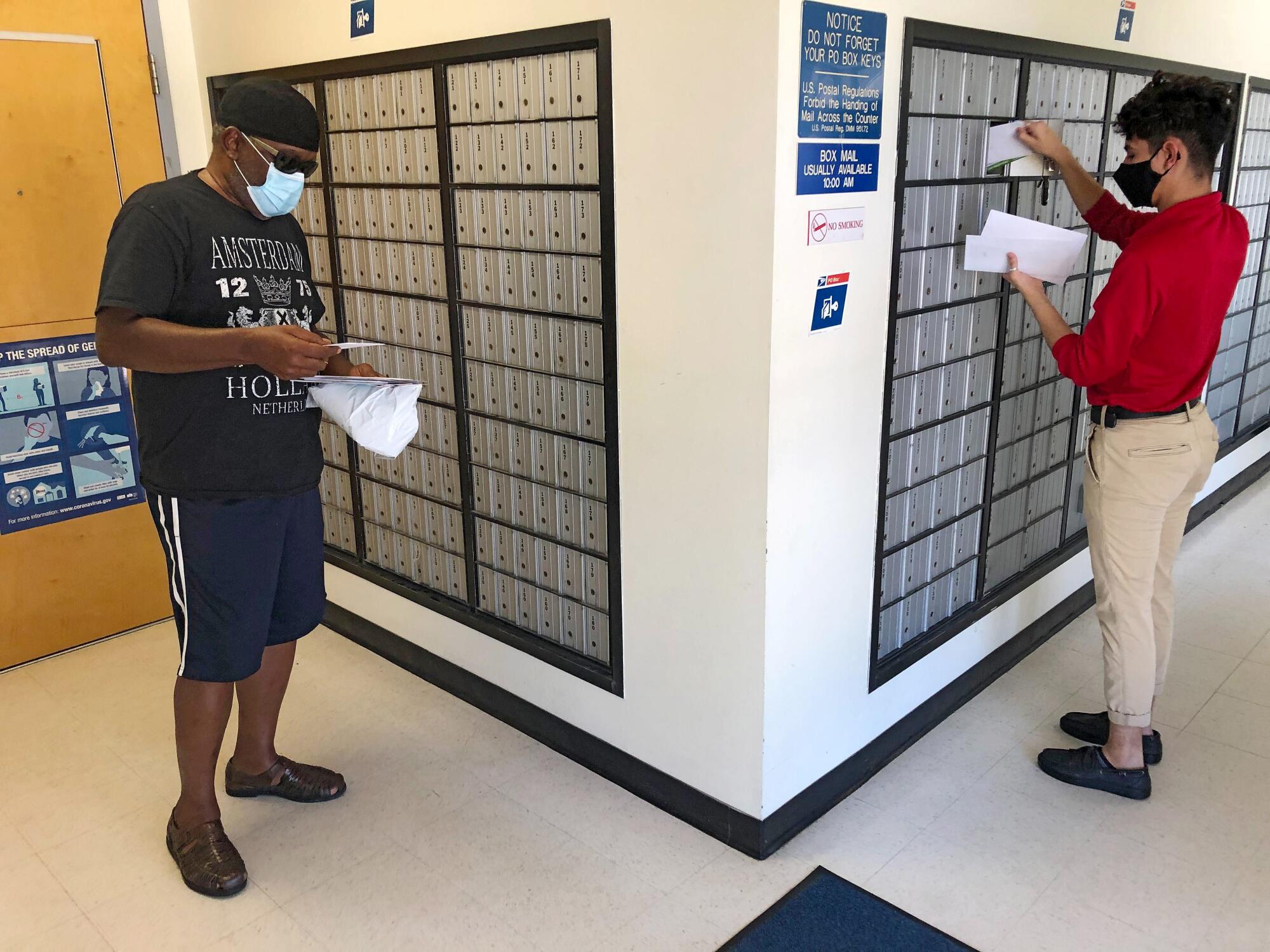

Red and blue states that had offered the option only to a relatively small number of residents were suddenly scrambling to expand mail voting to as many people as possible to prevent the spread of COVID-19 at polling places. Voting rights advocates saw it as a chance to educate lawmakers and voters about the long-term benefits of moving away from casting ballots in person.

Then came President Trump’s baseless allegations of widespread mail ballot fraud.

Two years later, access to mail voting looks radically different from state to state, mirroring a broad partisan divide in voting policies.

Republican-led states, echoing the former president’s unfounded fraud claims, have passed laws restricting access to ballot drop boxes, created new requirements for verifying voters, limited who can return a voter’s ballot and made it harder to correct mistakes on mail ballots. Democratic states have moved in the opposite direction — or attempted to do so. Legal challenges, failed ballot initiatives and constitutional hurdles have hampered efforts to make mail voting easier, particularly in the Northeast.

Voting rights advocates say mail voting makes the process easier for people who have difficulties traveling to polling places and helps blunt the impact of policies that suppress voter turnout, such as polling location closures that have a disproportionately negative effect on Black and Latino communities, leading to longer lines. They have raised concerns that the policies Republicans have enacted to prevent mail ballot fraud — despite existing safeguards such as signature verification and ballot tracking — are discriminatory and disenfranchise people of color and low-income voters.

“It’s getting to the point where, really, we’re seeing these two democracies emerge,” said Liz Avore, a senior policy advisor at the Voting Rights Lab, a nonpartisan advocacy group that tracks state election laws. “Your ZIP Code really determines what kind of access you have to the ballot, which is concerning.”

During the 2020 election, Trump repeatedly attempted to cast doubt on the security of mail ballots, though he has used the practice himself, claiming without evidence that the general election would be “rigged.” After he lost, his campaign filed more than five dozen election lawsuits that failed to turn up proof of widespread fraud that would have changed the outcome of the election.

The lasting impact of his claims has led to stark differences between how Democrats and Republicans view mail voting. Democratic voters were nearly twice as likely to support allowing voters to request an absentee ballot without a documented excuse or vote early in person as Republicans were, according to a June 2020 Pew Research Center poll. Several Republican nominees for secretary of state across the U.S. have campaigned against mail voting, including Arizona candidate Mark Finchem, who has denied the results of the 2020 election and, like the former president, has himself voted by mail.

Vote-by-mail policies exist on a spectrum. Eight states, including California, offer universal mail voting, which means registered voters automatically receive a ballot for elections. About a dozen states offer mail voting in smaller counties or in state and local elections.

In 15 states including Texas, voters can request an absentee ballot only if they provide an approved reason for voting by mail, such as being outside of one’s voting jurisdiction, working as a poll worker or having an illness or disability that prevents in-person voting.

Conversely, 27 states and the District of Columbia allow voters to request a mail ballot without providing a reason. Some of those states allow eligible voters to sign up to receive an absentee ballot on an ongoing basis.

Within those states, there are varying rules dictating how ballots are verified, when and how ballots should be returned, and what happens if a voter’s signature doesn’t match the one on file or they don’t properly fill out their ballot.

California has been shifting toward remote voting since 1978, when it became the first state to allow voters to request an absentee ballot without a specific reason. In 2016, the state enacted the Voter’s Choice Act, which began the process of allowing counties to apply to start sending all voters a mail ballot. The pandemic moved up the timeline for bringing the entire state over to mail voting — in 2021 the state passed a law requiring counties send a ballot to every voter.

“We’ve taken all the excuses off the table,” said Sen. Alex Padilla (D-Calif.), who served as California’s secretary of state in 2020 and oversaw the shift to vote by mail. “There’s no other states that’s bigger than us, that’s as diverse as us. And so to say, ‘Oh, it’s too expensive or too complicated,’ — no. If [California] can do it, any state can do it.”

On the other end of the spectrum, states such as Texas, Georgia and Florida responded to the 2020 election by overhauling their election laws in ways that add hurdles to mail voting. In Georgia and Florida, which allow no-excuse absentee voting, new laws have limited when drop boxes are available and where they can be located, and added requirements for how drop boxes are monitored.

Advocates of increasing drop box access say they are secure and a more reliable option for returning ballots on time than the mail system. Republican legislators, however, have argued that limiting and securing ballot drop boxes will help reestablish faith in elections.

“Removing drop boxes will help restore the trust that has been lost,” Butch Miller, a Georgia state senator and former lieutenant governor candidate, said last year during his failed push to eliminate drop boxes in the state. “Many see them as the weak link when it comes to securing our elections against fraud.”

In Texas, last year’s election overhaul made it a felony for election officials to encourage people to apply for absentee voting, even if they qualify under state law. The law also requires voters to include their state ID or driver’s license number, or the last four digits of their Social Security number to prove their identity.

“We’ve seen a number of states start to require ID numbers [on absentee ballots], which may sound reasonable on its face, but there are just so many implementation issues with this policy,” Avore said.

Election officials don’t always have a record of all the ID numbers voters can provide, and if a voter uses one election officials don’t have, or makes a mistake, the ballot is at risk of being rejected, she said. In Texas’ March primary, more than 12% of ballots were rejected, according to data from the Texas secretary of state’s office. In Harris County, the state’s most populous and home to Houston, rejections were highest in areas with large Black populations, according to an analysis by the New York Times.

Partisan battles over mail voting have also prevented legislative fixes to imperfect or unclear laws.

Pennsylvania authorized no-excuse absentee voting in 2019 as part of a broader election law, Act 77, that passed with bipartisan support. As the 2020 general election approached, critics sued to invalidate ballots that were returned without the outer privacy envelope or that were missing a date. Republicans, many of whom supported Act 77, worked to overturn it in September last year, arguing that the changes to absentee voting should have been enacted through a constitutional referendum. The state Supreme Court, which has a Democratic majority, voted to uphold the law.

For the record:

11:27 a.m. Oct. 20, 2022A previous version of this article said the U.S. Supreme Court ruled Oct. 12 that ballots left undated by Pennsylvania voters should not be counted. The decision, made Oct. 11, invalidated an appeals court decision that had required the counting of Pennsylvania mail ballots left undated by voters.

In a separate lawsuit, the Supreme Court on Oct. 11 invalidated an appeals court decision that had required the counting of Pennsylvania mail ballots left undated by voters. Pennsylvania’s acting Secretary of State Leigh Chapman has instructed counties to count undated ballots, citing a state court decision. Republicans filed a lawsuit Sunday asking the state Supreme Court to prevent the counting of those ballots.

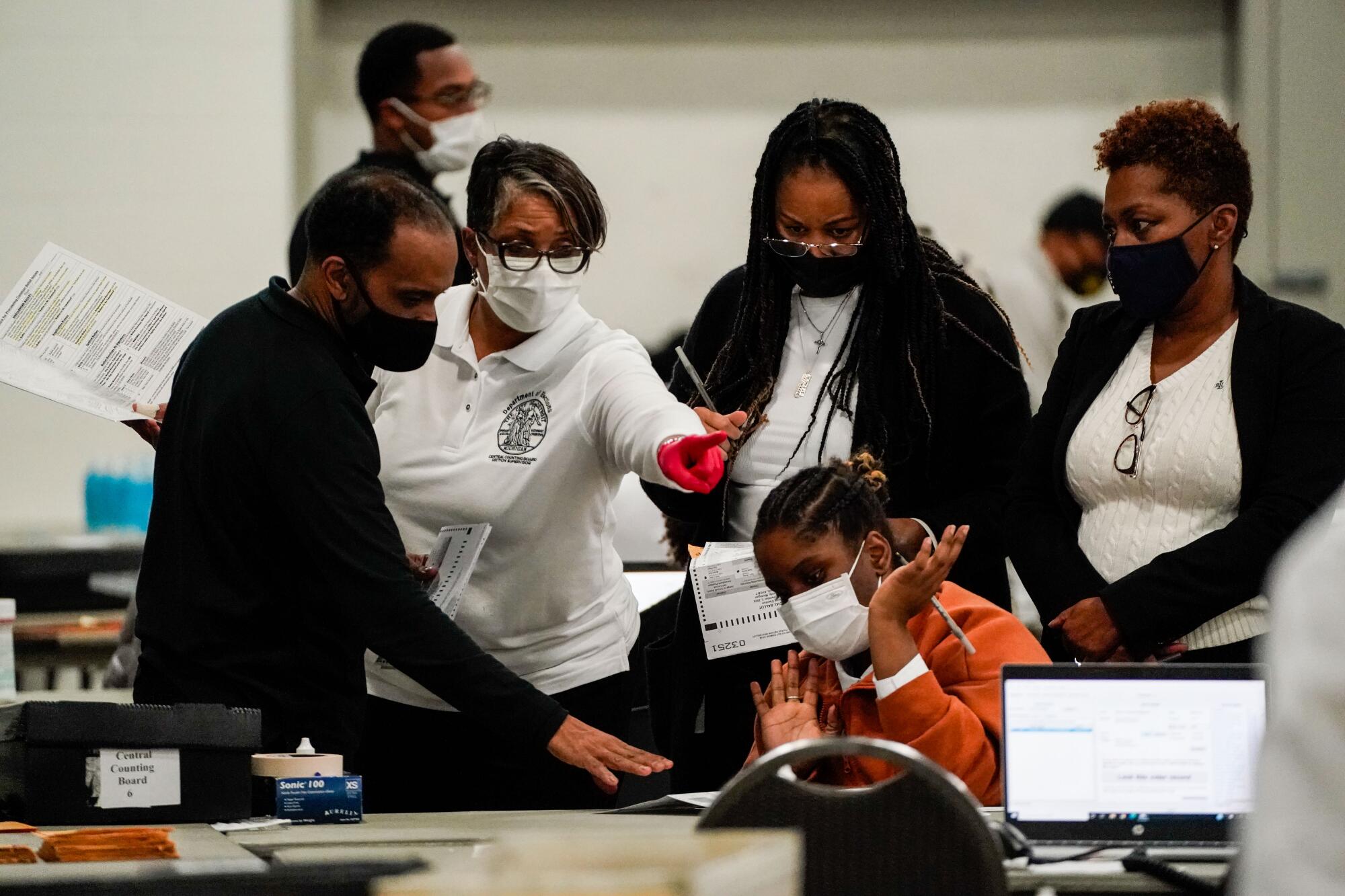

Then there is the question of when election officials should start pre-processing ballots. In other no-excuse absentee ballot states such as Florida, election officials have days or weeks to begin preparing ballots to be counted on election day. In Pennsylvania, that process can’t begin until the morning of the election, which led to major delays in the 2020 general election and the 2022 primary.

“That time between the polls being closed and all the votes being counted is dangerous,” said Al Schmidt, a former Republican city commissioner who helped oversee elections in Philadelphia. “The longer it goes on, the more likely you are to have people who have been deceived by all these lies act out.”

As Joe Biden’s lead grew in the state, Trump sought to stop the count of mail ballots there. In a tweet, the former president called Schmidt a “so-called Republican” who refused to “look at a mountain of corruption & dishonesty.” Schmidt told the U.S. House committee investigating the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol that he and his family received a torrent of threats after the tweets. Efforts to move up the start of ballot pre-canvassing have failed.

Blue states have also struggled to expand mail voting, particularly in the Northeast, where Vermont is the only state that holds all-mail elections. Delaware, Connecticut, New Hampshire and New York all require voters to provide a reason to request an absentee ballot.

“Northeast states, constitutionally, have all sorts of hurdles,” said Gerry Langeler, the director of research and communications at the National Vote at Home Institute. In many cases, expanded mail voting requires amending a state’s constitution, which often requires support from Republican legislators and voters.

New Hampshire Republicans blocked an effort last year to allow no-excuse absentee voting. In Delaware, the state Supreme Court overturned a 2022 law this month that would have allowed universal mail voting in the state. An effort to amend the state constitution’s language on absentee voting also failed this year. And in Connecticut, the legislature approved a proposed constitutional amendment to allow no-excuse absentee voting this year, but because it didn’t pass with a supermajority, the legislature must approve it again next year to put the issue to voters on the ballot.

After New York lawmakers passed legislation to put a no-excuse absentee voting measure on the ballot, voters rejected the proposed constitutional amendment in 2021. Out of 3.4 million ballots cast, 49% voted against the measure, 40% voted for it and 11% left the question blank. Voters also rejected two other election-related proposals on redistricting reform and same-day voter registration.

While Democrats did little to promote the initiatives, the state’s Republican and Conservative parties aggressively campaigned against them. The New York Conservative Party launched a “Vote No New York” campaign, which included a TV ad that stated no-excuse absentee voting has been “criticized as an invitation to fraud and a scam to rig the system.”

“It felt very much like the national effort to vilify and stop absentee voting,” said Susan Lerner, executive director of Common Cause New York, a good government advocacy group.

Western states, including some led by Republicans, have embraced mail voting for decades. Historically, vote-by-mail states have started off by allowing smaller counties to apply to hold all-mail elections before gradually expanding to larger population centers.

Utah held its first all-mail election in 2019 after first giving counties the option in 2012. Farther east, Nebraska started allowing counties with fewer than 7,000 voters to apply to hold all-mail elections in 2005. That population threshold was later increased to 10,000.

“It makes the process much easier for them and, given the lack of security concerns, it seems to be popular among the places that have been using it,” said Heidi Uhing, the director of public policy at Civic Nebraska, a pro-democracy advocacy group.

Uhing pointed to the June special election in the state’s 1st Congressional District. Republican Mike Flood beat Democrat Patty Pansing Brooks by just over 5 percentage points. Brooks performed better than recent Democratic candidates and won the district’s largest county — Lancaster, where the state capital, Lincoln, is — but Flood won the race because of wide margins in the surrounding rural counties. He garnered 88% of the vote in Stanton, an all-vote-by-mail county where 48% of eligible voters cast ballots.

“That shows getting people out to vote is just good for voting in general,” Uhing said. “There are some times that it might benefit one party over another, but overall, more voting is better for our democracy. And I think that should be a shared goal for all of us.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.