Column: California aims to shut up bullies and other bad actors so democracy can thrive

At the annual meeting of the League of California Cities, members were presented with a detailed report titled “Dealing With Disruptive Members of the Public.”

It included a history of dissent, a listing of several recommended actions and a typology of the protesters known to show up at City Hall: The meeting wreckers. The character assassins. The amateur city attorneys. (“I’ve conducted my own legal research.”)

That was 20 years ago.

In other words, the presence of outspoken citizens forcefully sharing their deep and abiding unhappiness with civic leaders is hardly new. It can actually be a healthy thing, accountability being vital to any system that aims to represent the people it serves.

But the level of animosity, violent threats and fly-off-the-handle behavior has hit remarkable heights during the COVID-19 pandemic, startling even longtime observers like Graham Knaus, head of the California State Assn. of Counties. He’s spent nearly a quarter-century involved in local government.

A public speaker at the Los Angeles City Council meeting climbed over a bench and moved toward council President Nury Martinez. Officers apprehended a second member of the public on the council floor moments later.

“This isn’t about people with different positions than their local officials,” Knaus said. “This is about severely disruptive behavior. It’s about hate speech. It’s about the increase in intimidation and the number of death threats that have been levied against local officials and their families.”

The result is a new California law that will make it easier to conduct the public’s business by spelling out just how and when bullies, bad actors and dangerous belligerents can be ejected so that school boards, city councils and other local government entities can do their work.

The recently enacted legislation, Senate Bill 1100, amends the 69-year-old Brown Act, which requires local governments to convene their meetings in public and guarantees the right of people to attend and participate.

Among other changes, it defines the meaning of “disrupting” — threatening the use of force, willfully ignoring rules of conduct — and gives the presiding officer the power to oust unruly individuals after they’ve received a warning.

The latter may seem like a small, and obvious, step, but it eliminates the need for a vote of the full body, which may be impossible if things escalate and a meeting is in shambles, or if members are forced to flee the dais for their safety.

The legislation is not, its co-author emphasized, an effort to muzzle dissent or keep anyone from speaking their mind as vociferously as they’d like.

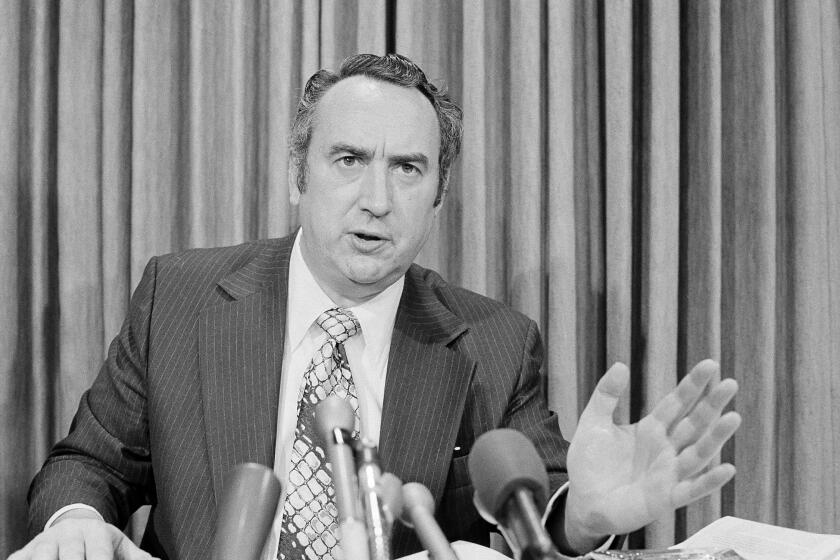

“I consider myself a 1st Amendment purist,” said Dave Cortese, a Democratic state senator from San Jose who spent more than a decade in local government, serving on the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors. If anything, Cortese argued, the legislation could enhance free speech by spelling out exactly how and when members of the public can be ejected once they’ve been fairly warned.

The law makes it clear that “if you’re going to be thrown out, it better be for something real and actual” that’s preventing a meeting from being held, Cortese said — not just for presenting an opposing viewpoint or speaking sharply.

And if somehow the legislation fails in practice, Cortese vowed, “we’ll fix it.”

“We’ll fix it regardless of who comes forward to expose those flaws,” he said. “Republicans or Democrats or ‘decline to states’ or people who don’t even vote but want to be able to come in and complain.”

Protests, sometimes rowdy and rude, have been a fixture for decades in the council chambers of big cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Diego. But in recent years, the practice has increasingly spread to small communities — the new state law stemmed from threats posed to members of the Los Gatos Town Council — and once-innocuous boards overseeing libraries, historical preservation and the like.

School board meetings, especially, have become battle zones in the fights over masks, remote learning and curriculum.

Blame it on the collective nervous breakdown the country seems to have suffered during three years of pandemic. Blame it on the bad behavior modeled by politicians at the national level and the inclination to turn every matter, however small, into a litmus test of red-versus-blue loyalties.

Robb Korinke, a consultant on local government who has spent two decades attending and monitoring city council meetings, also blames social media.

“Twenty years ago, you had a gadfly who knew they would get themselves on local-access cable,” Korinke said. “It’s a different thing when you know you can go viral. That’s really amped up the performative nature of a lot of this stuff.”

California Rep. Mike Garcia and others defending former President Trump by drawing analogies to Hitler cheapen history and violate the true victims.

The difficulty, of course, is knowing when and where to draw the line between disruption and dissent.

Some argue that shutting down a public meeting is itself a form of protest, signaling not only discontent but a deeper belief that a city council, school board or other governing body is so ineffectual, so inept or out of touch, that the only remediation is to cease its operation.

But Korinke poses a reasonable question: “Does your dissent override another person’s opportunity to speak?” Put another way, why should the loudest voices drown out all others?

“Bullying and intimidating behavior is not only coarsening discussion but having a chilling effect,” Korinke observed. “It prevents the average citizen from being able to participate in those meetings, or even wanting to. ... We wouldn’t allow that kind of behavior in a courtroom. So why do we allow it at city council meetings?”

By seeking to rein in the worst excesses without stifling protest, California’s new public meeting law strikes a welcome middle ground.

No one wants a bunch of sheep mindlessly doing whatever their government tells them. But that’s no reason to act like a jackass.

One in an occasional series on proposals to fix our politics and strengthen democracy. Read more:

More to Read

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.