News Analysis: Rare sense of ‘anxiety and urgency’ drives bipartisan talks on gun safety in Senate

WASHINGTON — It didn’t happen after 13 people were killed at Columbine in 1999, when 26 were gunned down in Newtown in 2012 or when 17 people were murdered at Parkland in 2018.

But the Senate is finally engaging in serious discussions over a bipartisan gun policy agreement that, if fruitful, proponents say would save lives, even if they result in a far less ambitious policy than what some Democrats say is necessary.

The horrific nature of the shooting of young children in Uvalde, Texas, as well as its timing — 10 days after a gunman massacred Black shoppers in a grocery store in Buffalo, N.Y., in what police described as a racially motivated attack — has created the political incentive for the first serious gun negotiations on Capitol Hill in decades. If a deal comes together and makes it to President Biden’s desk, it would mark the first gun legislation enacted since Congress passed the 1994 assault weapons ban.

Unlike in the wake of other mass shootings, when Democrats immediately called for ambitious gun policies including banning assault weapons that prompted swift rebuke from Republicans, the party’s lawmakers have opened the door to smaller-scale reforms. It’s the reverse of how Democrats in the closely divided Congress have responded on most policy issues this year: They have typically favored sticking with their ideals instead of making a modicum of progress.

“There’s a different sense of anxiety and urgency from the American public right now,” said Sen. Christopher S. Murphy (D-Conn.), who is leading the negotiations for Democrats and has a fourth-grade child, the same age as the victims in Uvalde. “I know that the urgency often fades [after prior shootings], but there’s something different happening out there in the country right now. And I don’t think that urgency and that demand for action is going away any time soon.”

A red-flag provision within the House legislation that passed Thursday stands out as perhaps the only piece that could pass the Senate.

Republicans, jolted by the deaths of 19 fourth-graders and two teachers in the Texas school shooting last month, signaled they would come to the table. The combination of the horrific death tolls in the two shootings and the targeting of children and Black grocery shoppers has struck a deeper nerve.

“The combination does have people looking pretty seriously,” said Sen. Kevin Cramer (R-N.D.). “There is definitely a serious effort to pass something by people on all sides. Not all people.”

For some Republicans, there is a feeling that if they don’t do anything, they risk a public backlash for appearing entirely unmovable on the issue of guns.

“The most common refrain I hear is, ‘Do something,’” said Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), the lead Republican in the negotiations.

“I am optimistic that we can find something that protects the rights of law-abiding citizens under our Constitution, under the 2nd Amendment, who I believe are not a threat to public safety, and focus on people with criminal records [and] people with mental health challenges,” Cornyn said.

Sen. Jon Tester, a Montana Democrat and self-described “big 2nd Amendment guy,” said letting mass shootings go without a response puts the rights of responsible gun owners at risk.

“It impacts 2nd Amendment rights across the board for a long time if we do nothing. The shootings are becoming all too often, all too common,” he said. “I think we need to work to empower gun rights, and having [guns] in the hands of criminals, in court-adjudicated mentally ill and terrorists, does not empower my rights as a gun owner.”

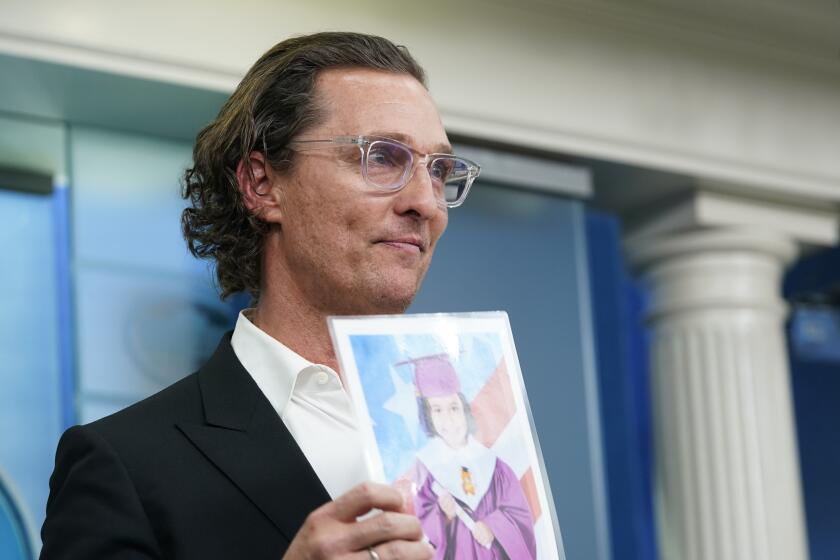

From the White House briefing room, actor Matthew McConaughey urges lawmakers to act on gun safety, in wake of mass shooting in his Texas hometown.

For two weeks, Murphy and Cornyn have been leading talks among a bipartisan group of senators on a framework that, if they can keep it together, would likely provide funding to bolster mental health treatment and school security as well as provide incentives for states to establish “red flag” laws, which would allow law enforcement to remove weapons from someone deemed a danger to others.

Republicans have taken off the table any kind of federal red-flag law. Several states already have red-flag laws, so it is uncertain how many more might be incentivized to create them under a federal plan.

Discussions have focused on whether lawmakers can raise the age to purchase a semiautomatic weapon or a handgun from 18 to 21. A few Republicans have opened the door to the possibility of an increase in the age requirement, though it appears unlikely to get enough support.

There are fulsome discussions around ensuring a person with a juvenile record of violence or mental health struggles cannot get hold of such a weapon upon turning 18, when many juvenile records are expunged.

“If there’s some way for us to look back into the sorts of records that would disqualify an adult if they had occurred post-18,” the background check system would find that additional people “should not be able to purchase a firearm legally,” Cornyn said.

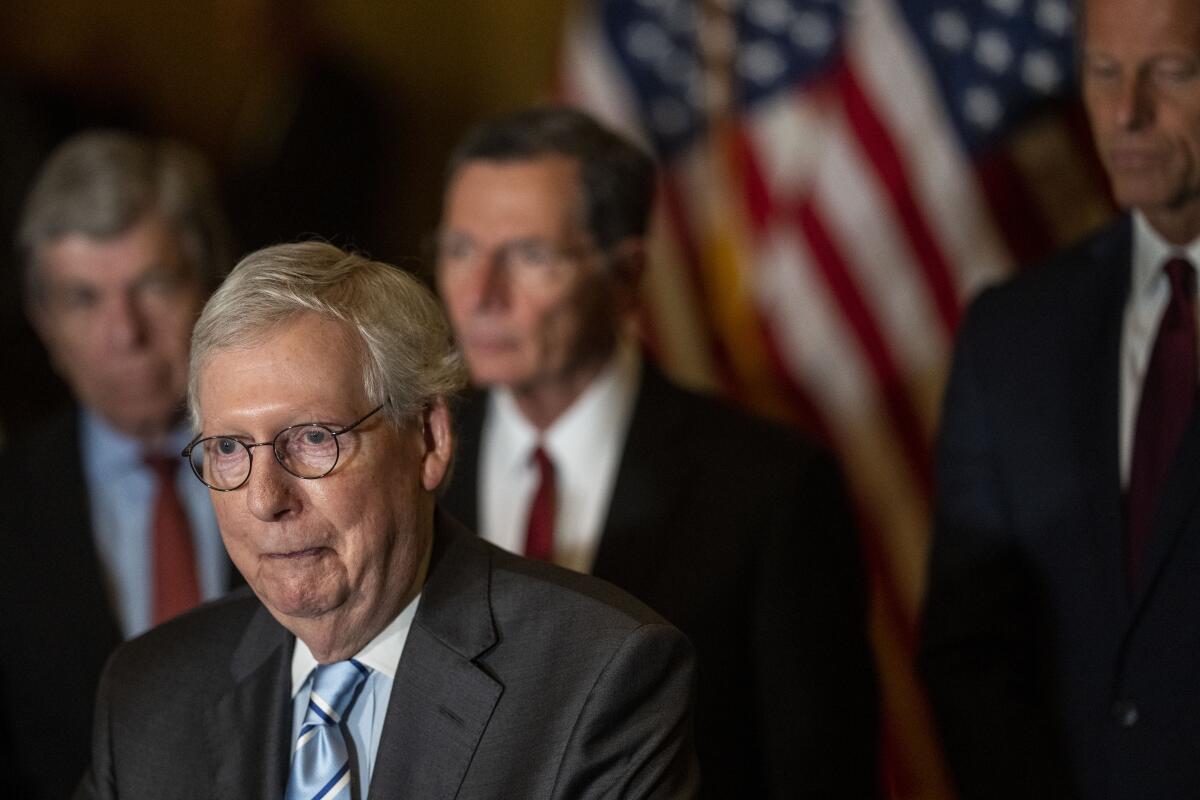

The Senate party leaders, Democrat Charles E. Schumer of New York and Republican Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, have blessed the negotiations, adding an imprimatur of seriousness to the talks.

Schumer has said that he has faith in Murphy’s role in the discussions and that the Connecticut senator won’t sign off on a bill that doesn’t have “teeth.” McConnell said he “personally would prefer to get an outcome” on policy that “directly relates to the problem.”

Still, there are plenty of skeptics of what the bipartisan group is working on.

“Sen. McConnell, Sen. Cornyn and anyone else who is tempted to even talk about gun control with Democrats should stand down immediately,” Missouri Rep. Vicky Hartzler, a conservative Republican running for the Senate, said in a Facebook post. “Conservative voters put them in those jobs to defend our rights, not negotiate them away.”

That attitude doesn’t bother Cornyn, who is leading the Republican side of the negotiations. He encouraged any Republican who feels the same way to “vote no.”

“I imagine there are a number of senators who, because they’re skeptical of this, will vote no,” Cornyn said. “We don’t need 100. We know we need at least 60, but my hope is we can build a broader bipartisan group than that. And I think we’re making good progress.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.