COVID-19 budget impasse halts aid to test and treat uninsured

WASHINGTON — With an urgent funding request stuck in Congress, a federal agency says it can no longer cover coronavirus tests and treatment bills for uninsured people and will stop taking claims at midnight Tuesday.

“The lack of funding for COVID-19 needs is having real consequences,” Martin Kramer, a spokesman for the Health Resources and Services Administration, said in a statement. “We have begun an orderly shutdown of the program.”

The Uninsured Program is an early casualty of the budget impasse between Congress and the White House over the Biden administration’s request for an additional $22.5 billion for the ongoing COVID-19 response. In operation since the Trump administration, the program reimburses hospitals, clinics, doctors and other service providers for coronavirus-related care for uninsured people, whose numbers total about 28 million.

Kramer said the program will next have to stop accepting claims for vaccination-related costs, after April 5.

Shutting off the spigot of federal money could create access problems for uninsured people, as well as consequences for the rest of society.

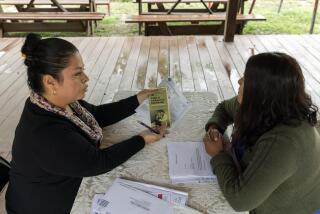

“COVID is a highly infectious disease, so we want people who think they might be sick to get tested and treated, not only for their health but for the community as well,” said Larry Levitt, a health policy expert with the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation. “If uninsured people now hesitate to get care because of the cost, we’ll see more cases and greater inequity.”

Levitt said he also worries vaccine providers could dial back their outreach efforts to uninsured people.

If the U.S. public health emergency ends, Americans would be vulnerable to a new coronavirus variant that sparks another COVID-19 surge.

Known as HRSA, the agency running the Uninsured Program is a unit of the Department of Health and Human Services. Officials said it receives about one million claims a day, and has reimbursed for care for millions of people during the pandemic. The program pays out about $500 million a week in claims, and more than 50,000 service providers have taken advantage of it.

HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra said last week that other initiatives could be blunted if the standoff with Congress persists. He singled out “Test to Treat,” a newly launched program through which patients who test positive can quickly get a supply of antiviral medications. They can take those medicines at home, reducing their chances of hospitalization.

“If you don’t have the dollars to let it fly, you’re stuck,” Becerra said.

COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths are down dramatically across most parts of the country, but there’s worry another surge may be on its way. Omicron variant BA.2 is spreading in Europe and Asia, and gaining ground in the U.S. as well.

It’s more transmissible than the original Omicron strain, but does not appear to cause more severe disease. Nonetheless if cases start going up again, hospitals might fill up.

With infections rising in parts of Africa, Asia and Europe, officials say they wouldn’t be surprised if new cases climbed again in the U.S.

The administration’s request for more money got snagged in a push and pull between Republicans and Democrats, House and Senate.

The biggest obstacle is in the evenly divided Senate, where Democrats would need 10 Republican votes to avoid a filibuster and approve the money. But Republican senators say that savings should be found among the trillions that Congress has already provided since the pandemic began two years ago.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi tried to find a compromise by agreeing to cuts with GOP leaders, but ran into problems with fellow Democrats.

Unless the money flows, the Biden administration says more Americans will feel the fallout.

A White House fact sheet says the government will not have enough money to provide boosters, or vaccines targeting specific variants, to all Americans. The supply of monoclonal antibody treatments will run out by late May.

Additionally, health authorities will be unable to procure enough quantities of certain treatments needed by patients with immune system problems. And sustaining a robust capacity for testing will be again become a challenge, repeating a cycle that has been a source of frustration from the beginning of the pandemic.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.