Column: There are some drastic ideas to overhaul California’s recall. Be careful, says one expert

If there’s a big winner of California’s gubernatorial recall election, apart from the revitalized incumbent, it’s probably Joshua Spivak.

Arguably the country’s foremost expert on the subject, Spivak cranked out a timely history, “Recall Elections: From Alexander Hamilton to Gavin Newsom,” and became the reigning authority on California’s madcap politics for dozens of news outlets worldwide. Appearing in Teen Vogue was a particular thrill, said Spivak, a political obsessive who is no one’s idea of fashion-forward.

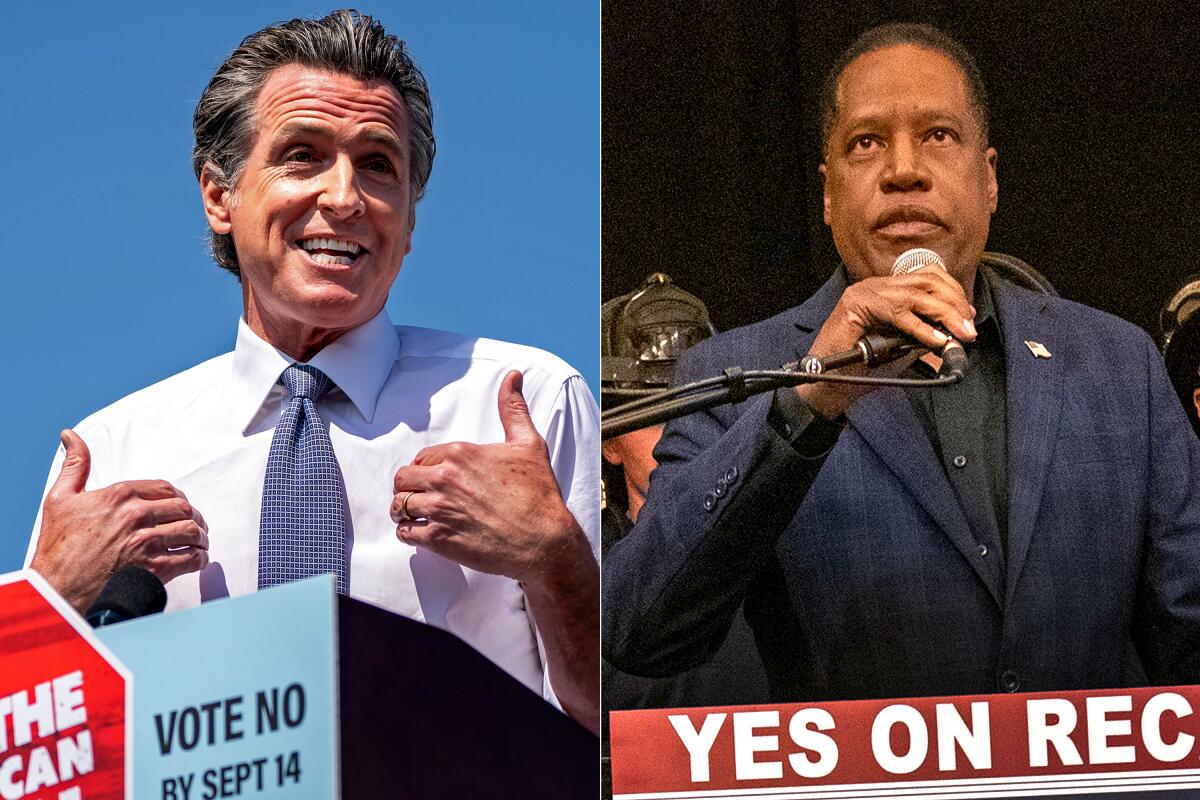

In the aftermath of the profligate exercise — $276 million in tax dollars torched so Newsom could romp past his Republican opponents — there has been no shortage of calls to reform the recall.

But Spivak, with his store of encyclopedic knowledge, warns against anything too drastic, and not just because a reduction in recalls might take away some of his fun. A senior fellow at New York’s Wagner College, Spivak tracks recalls — each year there are scores of them nationwide — as a hobby.

(What, you think extreme ironing and competitive dog grooming aren’t weird?)

It’s too easy in California to force a costly and wasteful special election like Tuesday’s vote.

Spivak worries that some proposals floating around would make it too hard to qualify a recall for the ballot and others, like automatically having the lieutenant governor replace an ousted governor, would only lead to more political mischief. “Then why not recall the lieutenant governor?” he asked.

It’s not as though California is particularly recall-crazy, said Spivak, who lives in the East Bay and makes his living in public relations. In the last 11 years, the state has had 116 recall elections, the overwhelming majority of them at the local level. Michigan had 175, the most of any state, and Oregon had just about as many as California and could surpass the state by year’s end.

But two California gubernatorial recall elections less than 20 years apart — representing half of all those conducted in U.S. history — have raised a number of concerns: about the cost, about the relatively low threshold for qualifying a recall, about the power and influence of money on the signature-gathering process and, not least, about the undemocratic nature of a system that allows a recalled official to be replaced with someone having far less support.

By way of reminder, even if a near-majority of the electorate votes against the recall, the targeted lawmaker is ousted and replaced by whichever replacement candidate receives a plurality of votes. In other words, if 49.9% of Californians had wanted to keep Newsom in office he would have been tossed out and California’s new governor would be talk radio personality Larry Elder, who received less than 30% of ballots cast in the Sept. 14 election.

Talk about weird math.

Of the 19 states that allow for gubernatorial recall elections, California has the lowest threshold to reach the ballot. It takes signatures representing just 12% of ballots cast in the last governor’s race. Spivak said a good idea would be changing that to 10% of registered voters, which would smooth out fluctuations based on a particularly high or low turnout election. (The latter helped lead to the 2003 recall that resulted in Gov. Gray Davis’ ouster.)

Changing the threshold would make it harder to force a costly special election and require more buy-in from California voters. In Newsom’s case, it took just under 1.5 million signatures to qualify the recall attempt. It would have taken the signatures of 2.2 million registered voters.

Another worthwhile reform, Spivak said, would be to copy the system used in Idaho. To recall someone there, the vote must surpass the number of ballots an official received when they won election. So ejecting Newsom would have required not just majority support for his removal but topping the more than 7.7 million votes he received in November 2018.

“It feels like this type of provision mitigates complaints that a small minority of voters choose to overthrow an elected official,” Spivak said.

Another not-bad idea, he said, is doing away with the bounty paid for signatures to qualify a recall, which gives an edge to well-heeled campaigns and individuals willing to spend a small fortune on qualifying petitions. But, Spivak noted, that could face a stiff legal challenge, given Supreme Court rulings that equate campaign donations with free speech.

(Legislation to do so is pending before Newsom; past efforts have failed.)

The effort to oust Sonoma County prosecutor Jill Ravitch failed. But it underscores the need for reform.

Spivak is less enthused about other proposals.

Forcing recall proponents to pay the cost of an election doesn’t seem appropriate, he said, any more than forcing someone to pay to vote. The recall, he notes, is enshrined in California’s Constitution. “Is there anything else like that,” he asked, “where we make people pay” to exercise their legal right?

“It’s not,” Spivak said, “what we do in America.”

He also frowns on suggestions the recall be limited to cases of malfeasance as opposed to, say, recalling someone because they belong to a different party or voters don’t like the way an officeholder walks or talks.

That would require a judge or election official to determine what constitutes malfeasance, Spivak said, which opens the door to all sorts of legal skirmishing and, inevitably, lengthy appeals. That could end up killing the recall, he said, or at least make it almost impossible to qualify an attempt.

Bottom line, Spivak said, there are changes that could improve the system, reign in some of the more egregious abuses and make it more small-d democratic. “But,” he believes, “it’s not some pressing need.”

Better, he suggested, for lawmakers in Sacramento to focus on homelessness, crime and some of the voter frustrations that led to the attempted recall of Newsom in the first place.

More to Read

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.