Column: ‘The battle just begins.’ Recall backers say toppling Newsom only first step in changing California

FRESNO — The day after Gov. Gavin Newsom is recalled — when and if it happens — Kellie Adolph will breathe a whole lot easier. Ka’ren Ketendjian says his morning coffee will go down smoother. Erik Traeger hopes and expects business at his Fresno CrossFit gym to pick back up again.

“We will be freer,” said Ketendjian, 59, a workers compensation attorney, who is counting on Newsom’s replacement to immediately repeal the mask and vaccine mandates that he and the others believe have strangled the economy and suffocated individual rights.

“I’m going to wake my kids up at 6 o’clock in the morning and I’m going to tell ’em, ‘Get ready for school, girls, you’re going without a mask!’” said Sean Soares, 40, who has pulled his two teenage daughters from class rather than comply with the COVID-19 cover-up required by the local school board.

What none of the recall supporters anticipate, even with Newsom’s hoped-for removal, is an end to the anger, upheaval and political conflict smoldering like one of California’s many out-of-control wildfires.

“I liken it to when we battled the Japanese” in World War II, hopping from one Pacific island to the next, said Joey Myers, 41, who runs a digital marketing firm. “It feels like Gavin is one island that we’ve got to take.” Then, he said, the focus and energy of recall proponents will turn to Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi “and other pillars we’ve got to crack and take down.”

Women approve of Newsom’s handling of COVID but are less enthusiastic about voting.

The Central Valley, long a conservative bastion, was a hotbed of anti-Newsom sentiment when activists set out to qualify the recall. Myers and the others agreed to meet this week outside a high-end coffee shop in Fresno to talk about their support for Newsom’s ouster more than a year before his term is due to end. Overhead, a gray haze of smoke and ash hung like a shroud over California’s agricultural heartland.

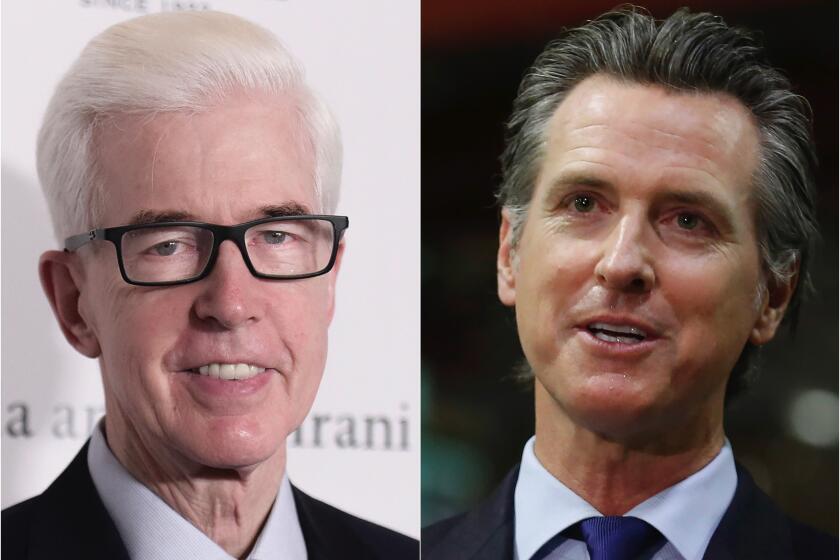

The five described themselves as leaning Republican, but more libertarian or conservative than wed to the GOP. None of them voted for Newsom in 2016, when he was elected in a landslide over businessman John Cox, one of 46 candidates on the recall ballot. The words they used to describe the Democrat included “corrupt” “tyrant,” “egotistical.”

“Hypocrite,” Traeger, 52, threw in.

They said Newsom arrogantly flouted the state’s pandemic guidelines — dining mask-less with political big shots, sending his children to private school while others were forced to learn remotely — and they questioned the widely accepted science underlying California’s COVID-19 mandates.

“It’s rules for thee, not for me,” said Adolph, 33, a paramedical tattoo artist. “He’s not in our homes with us, he’s not in the schools with us. He’s not listening to us, he’s just catering to the people who fund him.”

The group summed up the state of the state with a series of lamentations: “Disaster.” “Chaos.” “Disappointing.” “Heading toward Afghanistan.”

Myers repeated a line — “jewel to poop” — he’d earlier used to sum up San Francisco, the hometown of both Pelosi and former Mayor Newsom. Myers loved visiting the city with his wife and kids until it became, in his estimation, a slough of vagrancy, drug abuse and criminality. California, he suggested, has followed the same trajectory under Newsom as governor.

Resentments run deep in the Central Valley, long regarded as flyover country by those living elsewhere in California. Its cities are overshadowed by Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco, its Republican inclinations nullified in statewide elections by the greater number of liberal-leaning voters who hug the coast.

Grievances over taxes, water policy, environmental regulation and funding of the state’s controversial bullet train have simmered for years, if not decades, yielding a stew of animosity toward Sacramento, skepticism toward the media and distrust of politicians of any and all stripes.

Adolph and others expressed certainty that supporters of the recall would be punished should the effort to fire Newsom fall short. “I’m really genuinely scared of that,” she said, as the breakfast crowd thinned. “Lockdowns, more mandates. He’s going to make us pay for this recall if he wins.”

A narrow win by the Democrat might embolden challengers. But toppling a sitting governor is tough.

Even if it passes and Newsom is replaced, Ketendjian said, the political skirmishing won’t end.

“This is not South Dakota,” he said, but a sprawling and diverse state more akin to Texas and Florida, where local Democrats have fought efforts by Republican governors to forbid mask and vaccination requirements. “There will be a lot of tensions.”

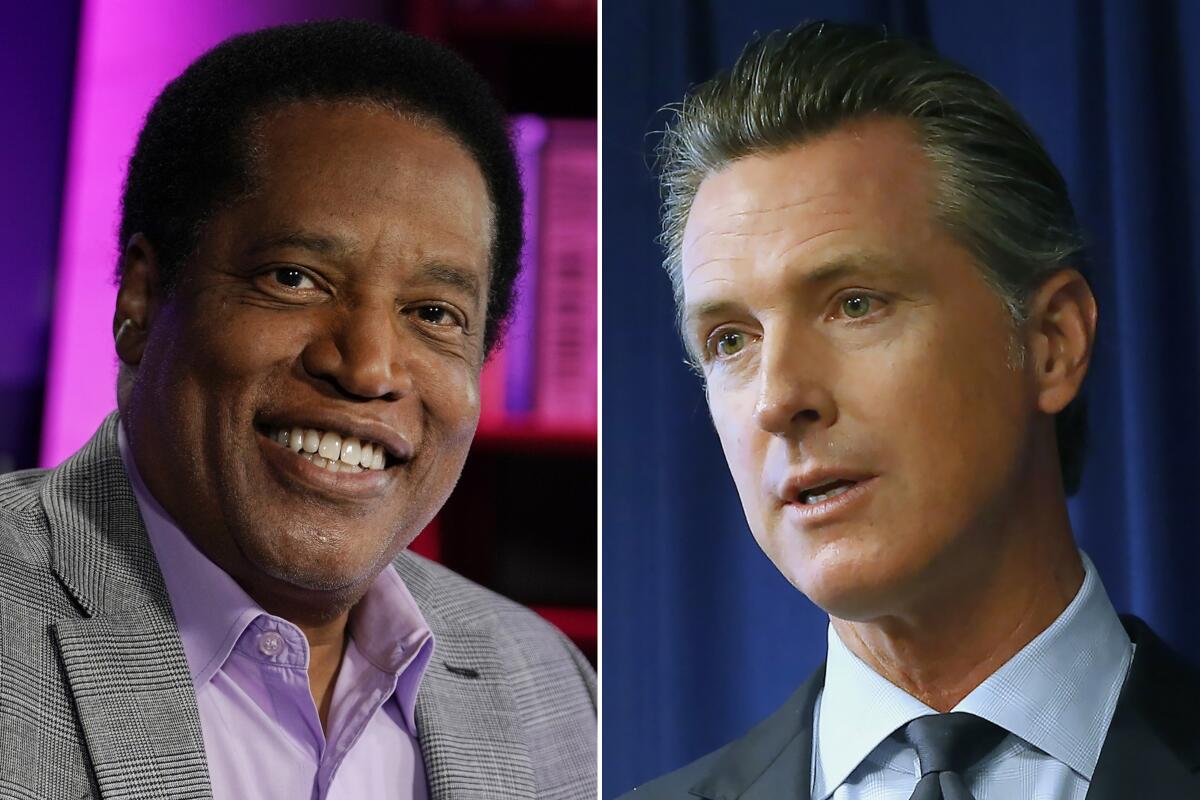

As a group they leaned toward Larry Elder, the conservative talk-radio host running to replace Newsom, though there was also interest in Kevin Kiley, the Republican state assemblyman from outside Sacramento and a leading critic of the governor’s pandemic policies.

Whoever wins on Sept. 14 will be expected by the five to crack down harder than Newsom has on criminals, do more to shelter the state’s massive homeless population and leave decisions on fighting COVID-19 up to local governments and individuals.

But for all their passion to be rid of the incumbent, there was underlying skepticism that replacing him would make a huge difference.

“We’re removing the biggest enemy of the people in California,” said Soares, sweeping a well-muscled arm through the air as if personally shoving Newsom aside. But, the real estate salesman went on, so long as all that top-down power resides in Washington and Sacramento it doesn’t matter who’s governor.

“They’re just going to end up being corrupted anyway,” Soares said.

Myers agreed. Recalling Newsom would make history and rock California’s political foundation, he said, “but it’s not going to take it down.”

“I think the battle,” he said, “just begins.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.