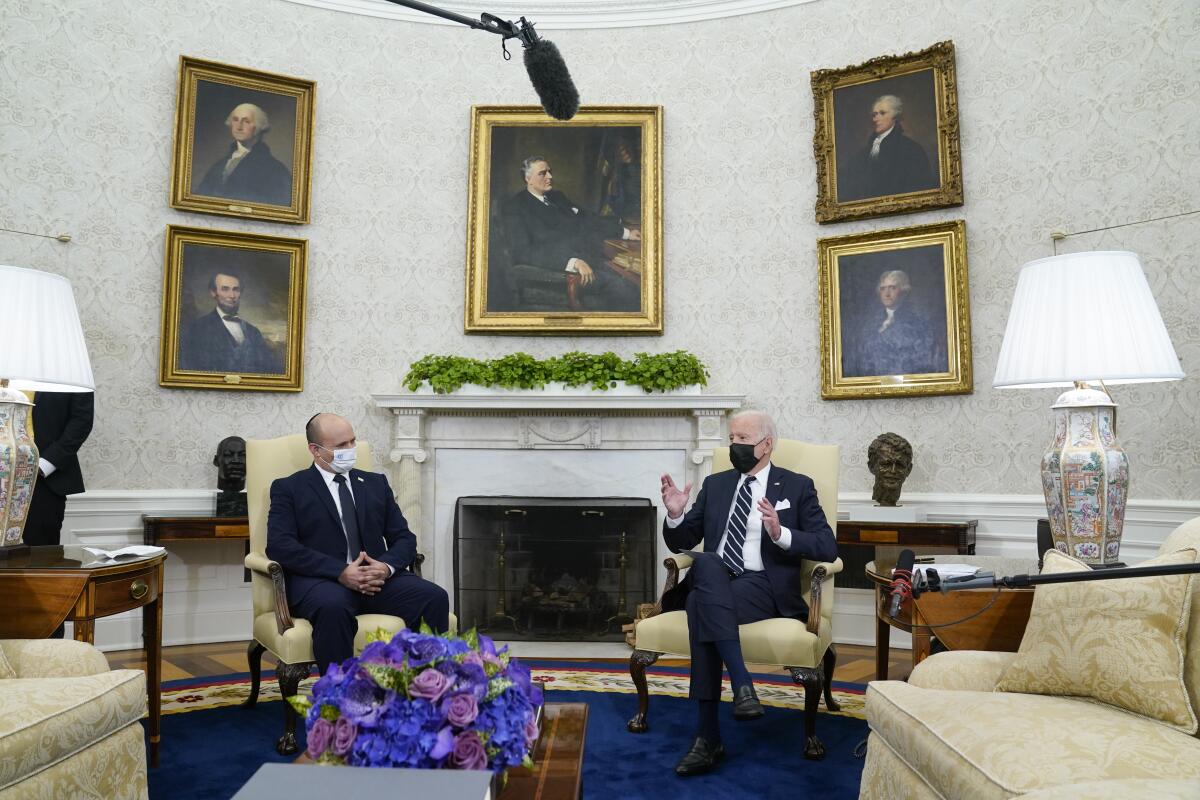

Afghanistan violence overshadows White House visit by new Israeli prime minister

WASHINGTON — President Biden’s meeting with Israel’s new prime minister would be a milestone event under almost any other circumstances, with the future of a key alliance and policies toward Iran’s nuclear program hanging in the balance.

But on Friday, the Oval Office encounter was overshadowed by Thursday’s terrorist attack in Kabul, which killed scores of Afghan civilians and 13 U.S. service members who were providing security for the evacuation effort there.

“The mission there being performed is dangerous and has now come with significant loss of American personnel, but it’s a worthy mission because they continue to evacuate folks out of that region, out of the airport,” Biden told reporters as he met with the new premier.

The attack prompted Biden to delay by a day his meeting with Naftali Bennett, the right-wing leader of a highly fragmented coalition government that banded together to oust Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s longest-serving prime minister.

Bennett and Biden had never met — a sign of Bennett’s status as a relative political novice, given that Biden has spent decades crisscrossing between world capitals.

The two leaders seem to share no political positions and will probably remain at odds over whether to rejuvenate the nuclear agreement with Iran. Biden wants it back, and Bennett cheered former President Trump’s decision to withdraw.

“The main issue we’re going to be talking about today here is Iran’s race to a nuclear weapon,” Bennett told reporters during a break in his private meeting with Biden.

“We talked about it inside the room,” he said. “I was happy to hear your clear words, that Iran will never be able to have a nuclear weapon, and you emphasized that we will try the diplomatic way but that there’s other options that will work out.”

Biden said he would try to revive the 2015 pact between Iran and other nations. “We’re putting diplomacy first and seeing where that takes us,” he said. “But if diplomacy fails, we’re ready to turn to other options.”

Both men are looking for an opportunity to normalize U.S.-Israeli relations after several years in which Israel has increasingly become a partisan issue in American politics. Republicans have tied themselves to Israel’s ruling right wing, a shift accelerated by Trump and Netanyahu, and Democrats have grown disenchanted with Israel’s indifference to the Palestinians, who remain under occupation.

“One thing that both of them care the most about is getting over this rancor in the relationship in the past few years and the polarization beyond that,” said Ilan Goldenberg, a Middle East expert at the Center for a New American Security, a Washington think tank, who has advised the Biden team.

Israeli parliament’s vote of confidence in the new government pushes Netanyahu aside, installing another right-wing leader, Naftali Bennett, in his place.

Michael Doran, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, a conservative think tank in Washington, said that “they have a shared interest at the moment in the appearance of very productive and cordial relations.”

Both sides are already taking steps in that direction. Biden called Bennett to congratulate him hours after he became prime minister in June, and a senior administration official gushed over the “truly remarkable” government that Bennett represents, describing it as a “big tent” that shows “people of divergent views can come together to solve big problems.”

Bennett had sounded hopeful before taking off from Israel, saying that “there’s a new government in the U.S. and a new government in Israel, and I bring with me from Jerusalem a new spirit of cooperation, and this rests on the special and long relationship between the two countries.”

U.S.-Israeli ties have always been strong, but the relations among leaders have ebbed and flowed.

President Obama and Netanyahu — who served as prime minister from 2009 to June of this year, and from 1996 to 1999 — did not like each other. Netanyahu dealt the ultimate diss when he traveled to Washington to speak before the U.S. Congress, with no formal notification to the White House, and then used the occasion to attack the Iran nuclear deal Obama was negotiating.

Under Trump, the U.S. became more aligned with Israel than ever. But critics said that relationship was built more on personal ties between Trump and his family and Netanyahu — not on the legal principles that had long governed U.S. dealings with Israel and the Palestinian territories, which the former president did his best to sideline and punish.

Ideologically, Bennett is probably closer to Trump. He embraces some of the Israeli right’s most radical positions, rejecting the creation of a Palestinian state and annexing much of the West Bank claimed by Palestinians to become part of Israel.

But he also recognizes the way the excessiveness of the Trump years damaged the bipartisan U.S. support for Israel that the nation has enjoyed for decades. And given his politically precarious status as the leader of a fragile parliamentary coalition, Bennett wants to demonstrate that he can deliver a strong relationship with his country’s most important ally.

Benjamin Netanyahu is no longer Israel’s prime minister. Now, the coalition that ousted him faces a hard challenge ahead: leading together.

Even though the Biden administration has sought to revive the Palestinian role in the conflict and peace talks to resolve it, Bennett made clear his focus was Iran.

To the alarm of the international community, Iran has been stepping up its processing of potential nuclear materials after the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the landmark nuclear pact.

Since Trump pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal in 2018, “Iran’s nuclear program has just dramatically broken out of the box and is accelerating from week to week,” said a Biden administration official who requested anonymity to speak about Bennett’s visit before his arrival.

The official added, “It’s a very alarming picture.”

Acknowledging the threat Iran poses to Israel, the administration is waiting for the new hard-line government in Tehran to return to negotiations in Vienna, the official said. So far, it has been unwilling to do so. If talks don’t work, the official noted, there are other ways to pressure Iran.

Israel is believed to be responsible for several bombings of Iranian facilities in recent months, attacks that earned little international condemnation.

Doran expects Bennett will want to continue a campaign of sabotage, which would put Biden in a difficult position.

“There’s no way Biden can get a deal with Iran, and wink and nod at the Israelis at the same time,” Doran said.

Though the two leaders do differ sharply on Iran, Biden may be content to have an Israeli prime minister who appears easier to deal with.

Susie Gelman, executive board chair of the Israel Policy Forum, a U.S.-based advocacy group, said what Bennett brings to the relationship is “a new face.”

She said Bennett, the son of a Berkeley couple who immigrated to Israel, would be unlikely to offer dramatic proposals for the Palestinian conflict, or be willing to budge on Iran, but would try to build a “personal, more positive relationship.

“He can be very charming,” she said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.