Column: Feinstein’s recall history offers a lesson for those aiming at Newsom — you better not miss

SAN FRANCISCO — In 1983, Dianne Feinstein was San Francisco’s accidental mayor. She’d twice failed to win the office and was serving only because her predecessor was assassinated and, as head of the Board of Supervisors, Feinstein was first in line to replace him.

A year later, she was a national political celebrity.

A list of America’s 10 “most influential women” placed her alongside First Lady Nancy Reagan, Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and civil rights leader Coretta Scott King. Her glow nearly landed Feinstein on the presidential ticket before Democrat Walter Mondale chose Geraldine Ferraro instead.

What raised her stature was an attempted recall, which failed in spectacular fashion and “totally transformed her career,” in the words of Clint Reilly, the Democratic strategist who helped engineer Feinstein’s landslide victory nearly four decades ago. With so much national focus on the out-of-ordinary election, “All of a sudden, Dianne was vice presidential material.”

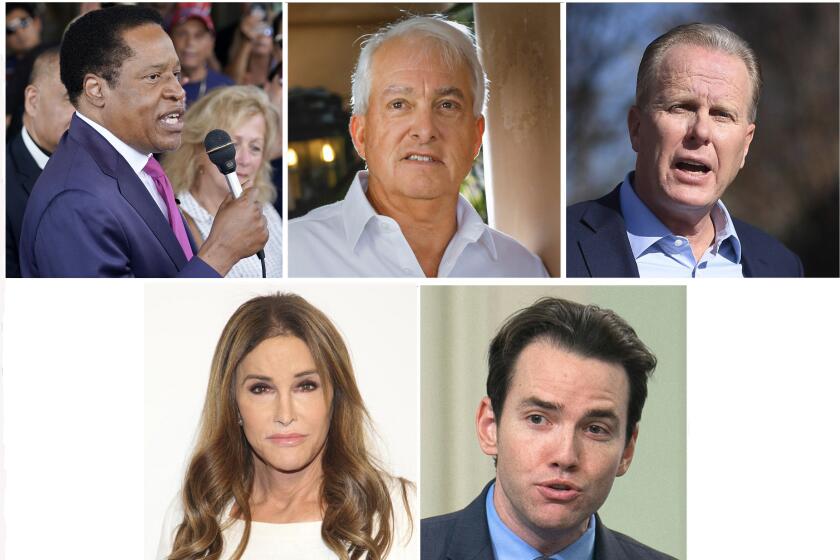

As the effort to recall California Gov. Gavin Newsom moves forward, candidates line up to replace him.

There are vast differences between then and now, between the attempt to oust San Francisco’s mayor — who has gone on to a 28-year career in the U.S. Senate — and the drive to remove California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

For one thing, if Newsom manages to beat back the recall, it won’t be with the support of 80% of Californians. (Feinstein’s attempted removal was rejected by 82% of San Francisco voters, to be precise.)

She didn’t fight for her job amid an epochal event like the COVID-19 pandemic, or do something stupid like dining maskless with a lobbyist at a swanky Napa Valley restaurant while urging others to stay home.

There was no Caitlyn Jenner bidding to replace Feinstein, or any big-name opponent for that matter.

But there are enough similarities to inform the strategy of Newsom as the governor seeks to survive a threatened recall and to give a warning to Republicans hoping to short-circuit the Democrat’s career by forcing an early referendum on his uncompleted term.

“A recall campaign which was overwhelmingly defeated might well provide the show of strength which guarantees the Mayor an easy re-election campaign six months later,” Reilly wrote Feinstein in a January 1983 strategy memo.

The same could happen if Newsom beats the recall, even by a lesser margin. If Republicans, grasping for political relevancy in California, can’t knock him off in September, why suppose they will be any more successful next year?

Should Newsom prevail — which Reilly expects — “Gavin’s going to be reelected on the night of the recall,” he predicted.

The effort to oust Feinstein was the kind of weird spectacle that helped give San Francisco its quirky reputation as the odd-sock drawer of America.

The driving force was a group calling itself the White Panthers, a Haight-Ashbury commune organized around “the right to bear arms, smoke dope and listen to loud rock and roll,” as Jerry Roberts described the insurgents in his definitive Feinstein biography, “Never Let Them See You Cry.” (When the recall qualified, the mayor wept in the privacy of her City Hall office.)

“We are people who support the Constitution” and, in particular, the 2nd Amendment, the group’s leader, Thomas W. Stevens, said at the time. “Also, we’re Communists. We’re on the Marxist, Leninist, Maoist, Castroist side of most questions.”

Which was pretty out there, even by San Francisco standards.

The animating issue was a ban on handguns that Feinstein pushed through a divided Board of Supervisors and signed into law. It was a powerfully resonant piece of legislation, coming four years after Mayor George Moscone was shot and killed in his City Hall office with a handgun also used to assassinate gay Supervisor Harvey Milk.

A state appeals court struck down the measure, but the White Panthers accused Feinstein of a “tyrannical attack” on their constitutional rights and sought to recall her anyway. They received strong support from LGBTQ activists infuriated by the mayor’s veto of legislation that would have given same-sex couples the equivalent of a marriage license and extended city-employee benefits to same-sex partners.

Despite those critics, Feinstein was viewed favorably by the broader electorate, much as Newsom is today. The recall effort, and especially the White Panthers, weren’t nearly as well regarded.

So the mayor’s campaign set out to maximize turnout, to make sure a small but energized minority didn’t prevail in an election most voters ignored. The idea was not just to beat the recall; the aim was to crush it through an on-the-ground effort unlike any the city had seen.

The campaign purchased 100 ironing boards and stationed campaign workers outside supermarkets and other heavily trafficked areas, where voters were urged to apply for mail-in ballots. (By using ironing boards instead of a table, three people could work at a time and hail passersby at eye level.)

Mail ballots were something of a novelty at the time, but the return rate allowed strategists to track who had voted and who needed a nudge. A record 70,000 absentee ballots were issued for the recall; Feinstein’s campaign was responsible for more than 60,000 of the applications.

The night of her April 1983 victory, the mayor was buoyant, and she told reporters the next day at City Hall that anyone who ran against her in November was “going to be creamed.” She was right. She bested a field of political nobodies to win reelection with 80% of the vote.

History will be a lot kinder to Sen. Dianne Feinstein than today’s dismal approval polls.

A statewide campaign is far different from one waged within the insular confines of San Francisco, but there are parallels beyond the fact that both Feinstein and Newsom served as mayor of the city.

The cost of the current effort, about $275 million, is an issue today as it was in the attempt to take down Feinstein. Recall proponents also have to explain, as they did then, why the vote is so pressing it has to be held just months ahead of a regularly scheduled election.

The Republican Party isn’t the White Panthers — not even close — but the GOP has its own brand of nuttiness, and Newsom is doing everything he can to link his opposition to unhinged QAnon and Trump supporters.

Backers of the recall have depicted Newsom as a sceptered monarch, sitting on a throne and issuing heedless decrees from Sacramento.

If there’s one lesson Republicans might take away from Feinstein’s experience — which left her politically much, much stronger — it’s summed up in a line from “The Wire,” HBO’s gritty crime drama.

“You come at the king,” said stickup man Omar Little, “you best not miss.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.