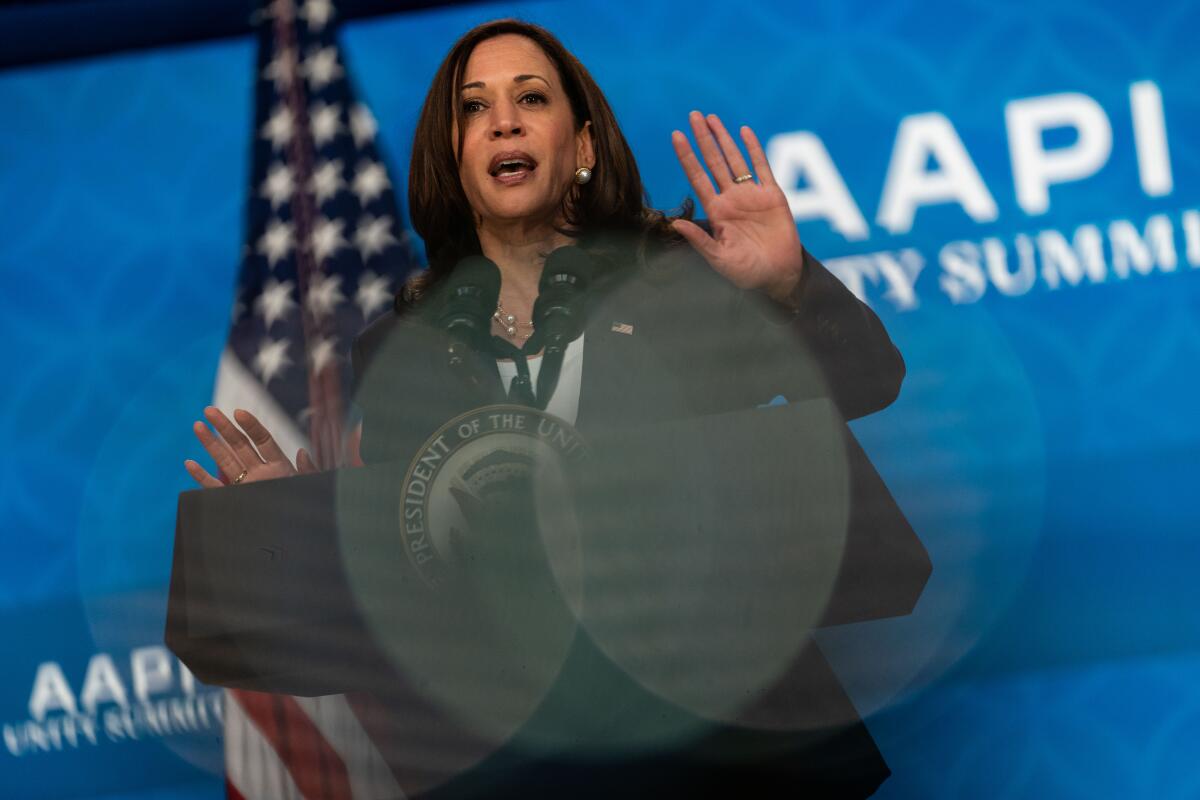

Kamala Harris isn’t getting any honeymoon, and some Democrats are fretting

WASHINGTON — Hours after Vice President Kamala Harris snapped at NBC News anchor Lester Holt last month in an interview from Guatemala, she was still showing signs of exasperation with questions about why she was not also going to the U.S.-Mexico border in her role dealing with waves of migrants to the U.S.

“Listen,” she said animatedly to reporters who’d accompanied her. “I’ve been to the border before. I will go again. But when I’m in Guatemala ... I think we should have a conversation about what’s going on in Guatemala.”

It was the kind of moment that has even supporters questioning her political acumen — underscoring why Harris, nearly six months into her term as a history-making vice president, consistently lags in polls behind President Biden, has failed to get the same honeymoon with voters, draws more critical media coverage and stands as a bigger target for Republicans.

“Just in terms of the public-facing stuff, it hasn’t been a stellar six months,” said David Axelrod, formerly the senior campaign and White House advisor to President Obama.

“You have limited opportunities to play the featured actor,” he added. “Mostly, you’re playing a supporting role. So if something goes wrong during those limited opportunities, they are magnified.”

Harris ended up going to the border last week, but the controversy over whether she would go provided grist for Democrats who see her flailing in the face of the Republicans’ attacks.

That Harris’ public support trails that of Biden, who is favored by a slight majority in most polls, is fairly typical for vice presidents, who by definition play backup roles, are less well known and sometimes serve as heat shields for their bosses.

Harris, as a Black and Asian woman, also is subject to racial and gender prejudice that neither Biden nor her predecessors faced. Women in public or private jobs, especially women of color, are often judged more harshly and held to higher standards than white male colleagues in high-level positions.

Still, some Democrats are beginning to worry that her sluggish approval numbers are indicative of a bigger problem for Harris, who as vice president ranks as the party’s potential heir to Biden, the oldest president in U.S. history at 78. They have many of the same doubts that have long dogged her, and contributed to her failed campaign for Democrats’ 2020 presidential nomination — about her style, political instincts and treatment of staff.

Politico reported last week about increased tensions within her office — including aides’ frustrations with Chief of Staff Tina Flournoy — while Axios followed with an article about friction between Harris’ staff and Biden’s. At least three Harris staffers have left in recent weeks and others are said to be considering the same. For now, those who’ve departed have been fairly low-level aides, and some churn is expected given the stress that comes with White House jobs.

Still, Harris has long had a reputation for high staff turnover, and as vice president she is working with an almost entirely new group of advisors, no longer in close touch with much of the political team in California that helped propel her career.

Allies say the hand-wringing is overwrought. Some complain that Harris has been hemmed in by the White House, even as Biden has given her thorny, perhaps impossible, tasks — notably, to seek ways to deter migration from Central America and to lead Democrats’ fight to expand access to voting.

Mark Buell, who has been Harris’ chief fundraiser since her first race for district attorney of San Francisco, said the White House seems to be giving her the toughest jobs without the full license to make her own mark.

“The administration needs to give her real authority, where she can hold a press conference and say, ‘Here’s what I think and here’s where I’m going,’” Buell said.

Administration officials say Harris is a valued voice behind the scenes and that her polling numbers should not be a surprise, given that she is playing a supporting role and lacks Biden’s decades on the national stage.

“She’s actually doing the hard work that a vice president does and not getting the credit for it because people have this sense that she should be out there doing something different,” said Anita Dunn, a senior advisor to Biden.

A senior administration official who would not agree to be quoted by name acknowledged that it’s “always part of the vice president’s role” to “take some of the heat” for the president, and called it “insulting” to suggest Harris’ assignments are too hard, as if “she needs to be protected.” The most important thing, the official added, is that the vice president is a trusted advisor and public messenger.

Harris is viewed favorably by an average of 44% of voters and unfavorably by about 47%, according to the Real Clear Politics average of recent polls. Biden, by contrast, is viewed favorably by 51% of voters, with about 43.5% disapproving. The difference in approval between them, in the high single digits, has been fairly consistent over past months.

A recent YouGov poll showed some of the factors behind the numbers. Biden did better than Harris among white voters across the board, but especially among white women with college degrees. While both get high approval from Democrats and low approval from Republicans, the intensity of support or opposition is different: More Democrats said they “strongly approve” of Biden than said the same about Harris, and fewer Republicans said they “strongly disapprove” of him.

Those differences reflect on the one hand Harris’ lukewarm support from the Democratic Party’s base, a problem since the 2020 presidential nomination race, and on the other the relentless attacks against her from conservative politicians and media.

“She’s not going to have a thermometer rating that matches the president’s. She just isn’t,” said former Obama pollster Cornell Belcher, referring to his own polling data. “She is subservient to the No. 1, just like he was subservient to the No. 1 when he was behind Obama.”

Donna Brazile, a friend and former Democratic Party chief, said it’s too early for Harris to worry about the polls. If they look the same a year from now, Brazile went on, then Harris should look at increasing her prominence. But for now, she should continue to literally stand behind or beside Biden at public events while advising him privately, Brazile said.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for all vice presidents is showing the public that they are capable of leading as commander in chief. For Harris, that challenge is all the greater, given that she is the first woman and the only woman of Black and Asian descent to hold the job.

“Middle white America” — people between the coasts — “they’re comfortable with an older white guy, and I don’t think I’m saying anything insane when I say that,” said Belcher, who is a Black man.

But he pointed out that Harris’ barrier-breaking identity is also a political asset, which will only be more valuable by 2028, when Biden, if he runs and wins reelection, would be ending his presidency. By then, given demographic trends, “we have an electorate that is probably about eight [percentage] points browner,” Belcher said.

Bakari Sellers, a co-chair of Harris’ presidential campaign and a CNN political commentator who remains a confidant, said Harris gets more scrutiny than her predecessors and less leeway than Biden.

For example, he said that Biden’s recent comments that put the administration’s infrastructure package in jeopardy were greeted as a “faux pas.” But, he added: “If Kamala Harris had done that, it’s stories about ‘Is she prepared?’”

Sellers does have advice: Harris should “stop advisor-sourcing information and just fall back on her gut.”

He said that Harris did not look comfortable when she said in Guatemala that would-be migrants should “stay home.”

“I’m pretty sure that came from the White House,” Seller said, “and that’s why it didn’t sound natural.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.