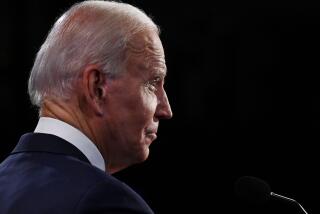

‘What an old politician understands’ — Biden turns the age issue to advantage

WASHINGTON — Donald Trump tried hard to defeat Joe Biden by hammering on “Sleepy Joe’s” age. He failed. And now, four months into President Biden’s term, his longevity — at 78 he’s the oldest president in history — may be proving to be one of his best assets.

Mellowed by age and the hard experience of half a century in politics, Biden has modeled an elder’s calm that fits the moment for a nation wearied both by crises and by his predecessor’s frenetic divisiveness. He’s also shown a focus, verbal discipline and self-assured boldness in his policy pronouncements that contrast with his intensity, gaffes and political moderation in past decades, to the surprise of even longtime associates.

“The reason Joe Biden won the nomination and the presidency was because everybody figured this was the right guy for the right time,” said former Sen. Ted Kaufman, his friend, advisor and longtime Senate chief of staff. “It’s like the Occam’s razor theory, where the simplest explanation is the correct one. The reason he’s so comfortable and sure-footed is because Joe Biden has been there before — he’s been around for almost 50 years learning what to do.”

While Republicans have struggled to define Biden in a critical way generally, their allies in conservative media have tried to exploit the age issue by portraying the president as feeble — focusing on his verbal stumbles, for example, and an actual one ascending the stairs to Air Force One. But such jabs have failed to resonate with the broader public.

Biden is not only the oldest U.S. president but also arguably the most well prepared. In dealing with Congress, he draws on the experience of 36 years in the Senate.

Former Sen. Alan Simpson, a Republican from Wyoming who served with Biden for half of that time, said Biden entered office having years-long relationships with numerous members of Congress, including Republicans, a deep understanding of how government works and the humbling experience of past defeats.

“One of the greatest disappointments of all time is to run for president of the United States and get hammered. He has been through the ups and downs of pain. And if he were sitting in the box at ‘The Phantom of the Opera,’ he would know every key on the organ,” Simpson said. “He will know exactly what is going on in Washington, D.C. And he has a divining rod of how to tell a phony son of a bitch, and that’s his greatest strength.”

But it was Biden’s subsequent eight years as vice president and then the four years after he left office in 2017 — spent reading presidential histories, reflecting on the Obama era and contemplating not just a final campaign but how he’d do the job of president — that have most informed his approach in the White House, according to several people close to him.

“The last 12 years have given him a lot of confidence in his judgment,” said Anita Dunn, a senior White House advisor.

A less-hurried Biden has appeared to savor the job right down to the little moments: picking a dandelion for First Lady Jill Biden on the walk across the South Lawn to Marine One, stopping his motorcade to pose for photographs with supporters along a Virginia roadside and engaging in long conversations with the Marines escorting him across the tarmac to Air Force One. On Tuesday, Biden, in his aviator sunglasses, reveled as he drove an electric pickup truck at a Ford plant in Dearborn, Mich., telling reporters, “This sucker’s quick!” before zooming down the track.

“This is the culmination of his political life and career,” said Leon Panetta, who served with Biden in Congress and in the Obama Cabinet, where the Californian was CIA director and Defense secretary.

As vice president, Biden was sometimes frustrated that he had his own ideas that differed from Obama’s — for example, their views on extending the war in Afghanistan (which Biden is now bringing to a close) and on budget negotiations with congressional Republicans — but he “had to be a good soldier,” Panetta added.

“He doesn’t have that anchor around his neck anymore,” Panetta said. “Now you’re seeing pure Joe Biden.”

So far, most Americans like what they see. An Associated Press/NORC poll released last week showed him with a 63% overall approval rating, the highest mark of his young presidency and a number few predecessors have reached.

“Despite the politics of the moment and the gridlock that’s still very real in Washington, there’s a sense that there’s a grownup in the job trying to do the right thing for the country,” Panetta said.

Biden has shown a determination to restore presidential norms and to address the crises he inherited with the follow-through that the erratic Trump neglected. He has pursued $6 trillion in New Deal-style initiatives to lift the country out of the pandemic and resulting economic downturn despite Democrats’ razor-thin majorities in Congress, and with the urgency of someone who knows that time — and political opportunity — is short.

Former Sen. Chuck Hagel, a Nebraska Republican who worked with Biden in the Senate and then as Obama’s secretary of Defense, has been struck by what he sees as Biden’s ability to see the big picture — viewing infrastructure as more than just roads and bridges, and framing his proposed investments in American workers as a matter of winning the global competition.

“He recognizes clearly that this is a defining time for America and for the world,” Hagel said. “I think that’s why, yes, he’s mindful of politics — you’ve got to be. But I don’t think he’s captive to a lot of hand-wringing. He’s seizing the moment, because he knows what’s required.”

Biden’s domestic agenda is in keeping with his campaign platform, aides say. Yet the scale of the proposed investments has startled Republicans — and pleasantly surprised many progressives who’d been wary of Biden’s long record of moderation.

“He hasn’t changed,” Kaufman said. “What has changed are the challenges that you face.”

In a TV interview last week, Biden said he’s tried to follow the advice of his late son Beau and stick to his “home base,” to govern based on his convictions. “Some things are worth losing over,” Biden said. “I haven’t done this, this long ... to do things that I don’t, I don’t believe.”

It’s indeed politically risky. But, Dunn said, “He knows that losing is not the worst thing that can happen to you.”

She pointed to Biden’s comments about the impact of the deaths of Beau in 2015 and of his first wife and infant daughter decades before, adding, “I think when he stops and he talks to people, that for him is more important than the cameras — those human connections.”

Although he has indicated he plans to run for reelection in 2024, at the age of 82, Biden stands apart from younger generations of Washington politicians so driven — as he long was — by zeal for media attention and by personal ambition. His staccato speeches, delivered with the help of teleprompters, are relatively short, plainspoken efforts to talk to Americans about their concerns — not to ensure that the public is talking about him.

Biden’s presidency has drawn comparisons to the third and fourth terms of former California Gov. Jerry Brown, who took office in 2011 at age 72 and drew on his decades of experience — including his two long-ago terms as governor from 1975 to 1983 and a stint as Oakland mayor — to pull his state out of a deep financial crisis.

Jim Newton, a Brown biographer, recalled the former governor’s memorable 2017 appearance in the state Capitol to passionately argue for cap-and-trade legislation. “This isn’t for me — I’m going to be dead!” Brown said. “It is for you!”

The broader public, Newton said, “came around to accept that he was just doing this because he thought it was best for California. It felt genuine.”

“And it feels to me like that’s what you’re observing with Biden,” Newton added. “There is something to be said for the authority and authenticity that comes from having reached one’s aspirations.”

Brown, now 83, agreed with the analogy.

“I thought I was pretty smart when I was governor the first time,” he said in an interview. “I thought I was pretty clever when I beat Jimmy Carter in the [1976] Maryland [presidential] primary. But I had nowhere near the insight you get from doing things and losing and seeing how things turn out.”

“I enjoyed it more at 80 than when I was 36 because I knew more. The pleasure of the office increases because you know more.”

Brown, who also replaced a celebrity in the executive office and faced major problems immediately, complimented Biden’s discipline in focusing on the pandemic and economic recovery efforts. Over a long career, Brown said, “You realize many things you do don’t have much impact, so that means you should focus on what you can accomplish. And that’s not 100 things.”

Even as Biden has presented himself as more a problem solver than a partisan, his agenda reflects clear political calculations recognizing the possibility that Republicans could capture one or both houses of Congress in next year’s midterm elections.

“The [country’s] hole is deep and the window is short with the midterms coming,” said Scott Mulhauser, a Democratic strategist and former Biden aide. “He’s got to dig the country out and be able to show some progress by the middle of next year. There isn’t a lot of math suggesting they ought to hold back. All signs are ‘Go.’”

Brown, who had the luxury of taking Democrats’ sway in Sacramento for granted in blue California, said it’s “imperative” that Biden retain the party’s majorities next year. “In one sense, he can’t be too adventurous. And he’s already being pretty adventurous and bold. But on other issues, he’s got to be very careful. Bold and cautious. And that’s what an old politician understands.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.