Column: A congressional shutout in Texas disappoints Democrats. Should they worry?

Texas has broken more Democratic hearts than all the George Jones and Willie Nelson songs combined.

The party hasn’t won a statewide election there in more than 20 years. Its last presidential candidate to win Texas was Jimmy Carter, back in 1976, when conservative white Democrats still roamed the Earth. (Like dinosaurs, they were a species destined for extinction.)

The latest setback came last Saturday, when Republicans nabbed the two top spots for a runoff in a special election to fill an open congressional seat representing a district outside Dallas-Fort Worth.

And with that, Democrats lost their best chance this year of expanding an eyelash-thin House majority.

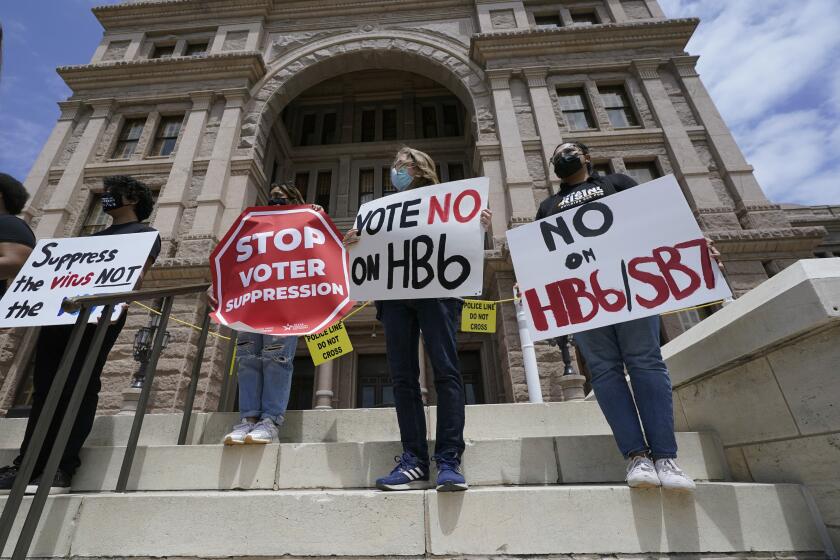

Efforts by Texas Republicans to pass voting restrictions tests the enduring relationship between the party and big business in the state.

There’s always a danger in drawing too many inferences from a single election — especially one held on a weekend in May 2021. But the outcome serves as a reminder of one of Democrats’ biggest worries in November 2022: that Republicans will turn out in huge numbers and Democrats won’t, costing the latter their control of the House.

Democrats had reason for optimism heading into the Texas contest, at least on paper. President Trump only narrowly carried the district in November after winning by 12 percentage points four years earlier. A growing Black and Latino population in Arlington, in the urban slice of the district, further heightened Democratic hopes.

But the party failed to unite behind a single candidate, and that hurt their top contender, Jana Lynne Sanchez, who came in third behind Susan Wright, the widow of the GOP congressman who most recently held the seat, and Republican state Rep. Jake Ellzey.

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Sanchez missed the runoff by just 354 votes, which was not bad in a field of 23 contestants. (Side note: “Big Dan” Rodimer, who moved to Texas from Nevada and dressed in cowboy clothing in a clumsy attempt at reinvention, finished well back in the pack.)

Sanchez’s showing might be considered a victory of sorts, up there with Joe Biden’s 5-point loss in Texas in November — a considerable improvement over Democratic presidential candidates of the last 20 years.

“Democrats have come a long way toward competing in Texas,” Sanchez said in a statement, bowing out of the congressional race, “but we still have a way to go.”

True, and true.

Both Sanchez and Biden performed credibly, but in the end, Trump won Texas’ 38 electoral votes, and one Republican or the other will represent the state’s 6th Congressional District.

The risk in over-interpreting a special election is the fact that they are, well, special — which is to say, out of the ordinary.

Sometimes the outcome serves as a harbinger of political change. In 1991, underdog Democrat Harris Wofford won a U.S. Senate seat in Pennsylvania, a contest that signaled the emergence of healthcare as a major issue and introduced the nation to two unsung strategists, Paul Begala and James Carville, who would soon help send Bill Clinton to the White House. A big part of Clinton’s 1992 platform was a promise to expand healthcare coverage.

Often, though, special elections are unique to their time and circumstance. In 2017, the two major parties poured a record $55 million into a House race in Georgia that Republicans won, extending their winning streak in off-year elections to 4-0. Democrats then went on to gain 41 seats and seize control of the House in November 2018.

Democrats have plenty of reasons to shrug off Saturday’s outcome.

The national party chose not to invest in the contest, mindful that the district will be redrawn by November 2022 as part of the once-a-decade reallocation of congressional seats and drafting of new political boundaries. Local Democratic groups and party leaders also steered clear of the contest, while outside interests split their support among candidates.

Party strategists also knew it would be hard to engage many in their base — younger, Black, Latino voters — who tend to pay less attention to elections like last Saturday’s.

“There are a lot of presidential-year-only voters,” said Lisa Turner, a resident of the district and state director of the Lone Star Project, a Democratic political action committee. “It’s super hard to get them to turn out for a gubernatorial election, let alone a special.”

Every 10 years, states must redraw congressional districts. Republicans control that process in more states than Democrats, giving the GOP the advantage.

Still, the paltry numbers should at the least give Democrats pause.

Some thought there might be an anti-GOP backlash after the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol and a winter storm that overwhelmed the state’s electricity grid and left millions of Texans shivering in the dark. It was hardly the finest hour for the state’s Republican leadership.

Nevertheless, GOP candidates won 62% of last week’s vote, and Democrats under 40%. Moreover, fewer than 80,000 ballots were cast, a steep decline from nearly 340,000 in November.

Heading into 2022, Republicans have history on their side: Since World War II, presidents have lost an average of 27 seats in their first midterm elections. The GOP will also have an upper hand in the redrawing of congressional boundaries, as they control the process in several states, including Texas. By some calculations, Republicans could secure the House majority, or least come close to gaining the handful of seats needed, through the redistricting process alone.

That means Democrats will need a whopping turnout, and have to hope that Saturday’s results were an anomaly and not a portent of things to come.

Otherwise — cue Willie Nelson — there will be a lot more blue eyes crying in the rain.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.