Biden says U.S. inoculation campaign entering a ‘new phase’

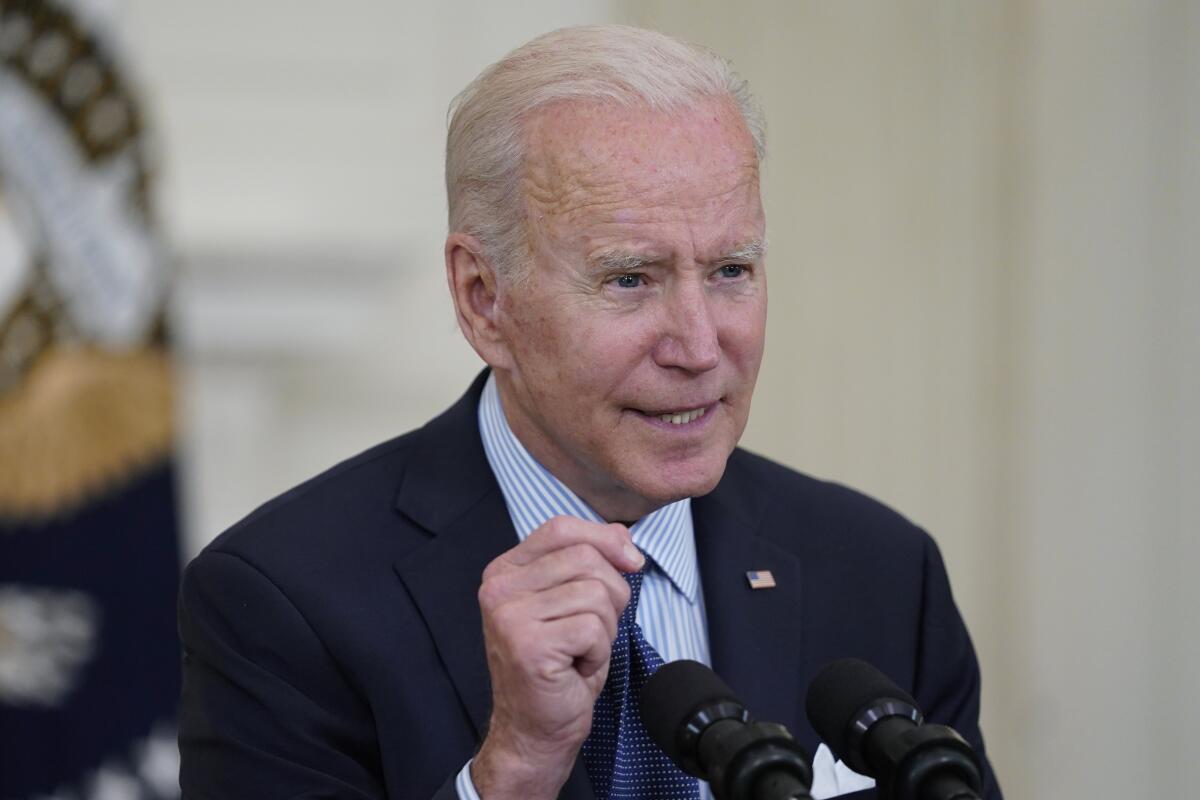

WASHINGTON — Confronting concerns that too many Americans aren’t getting vaccinated, President Biden said Tuesday that his administration was beginning a “new phase” of its COVID-19 inoculation campaign to convince more people to get a shot, and to make it easier for them to do so.

At stake is his promise to curb a contagion that has taken nearly 600,000 lives and cost millions of jobs in the U.S. — and make it safer for people to gather for Fourth of July barbecues, a symbolic goal that Biden set a little more than a month after taking office.

“We need you. We need you to bring it home,” Biden urged Americans from the White House. “Get vaccinated. In two months, let’s celebrate our independence as a nation, and our independence from this virus.”

President Biden promised to lead what had been a patchwork fight against the pandemic. But Republican resistance has left the U.S. exposed to continued infections.

With his remarks, Biden made official an ongoing shift in his administration’s focus from a logistical challenge to produce and distribute enough vaccines to a public education campaign to convince more Americans that it’s safe and important to get inoculated. To the consternation of health experts, the average number of shots administered daily has dropped by roughly one-third in the last three weeks, from 3.4 million to 2.3 million, according to statistics compiled by Bloomberg.

“We have enough vaccines,” Biden said. “Now that we have the vaccine supply, we’re focused on convincing even more Americans to show up and get the vaccine that is available to them.”

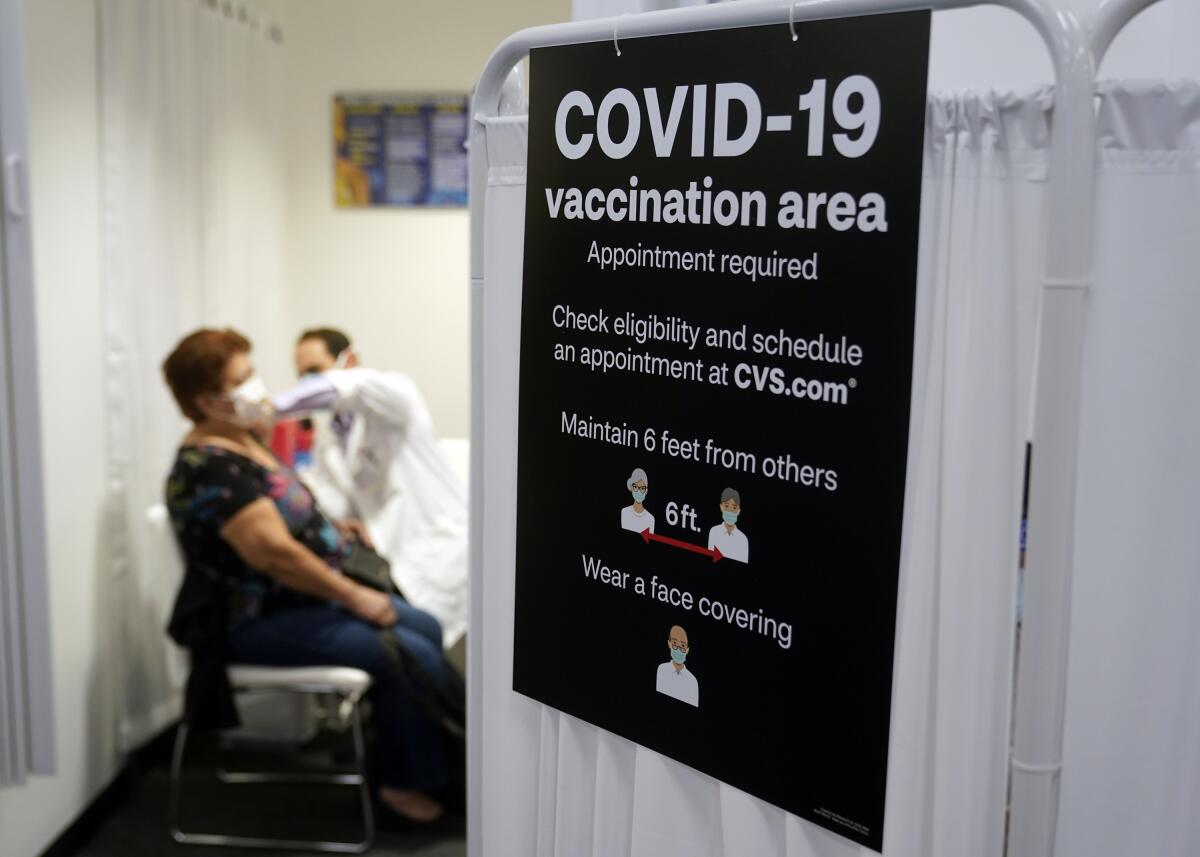

Biden said his administration was laboring to make it easier to get shots, unveiling a new federal website, vaccines.gov, to help people make appointments and directing pharmacies to allow walk-ins. Mass vaccination sites are being closed in favor of smaller clinics, doctor’s offices and mobile operations, part of what the president described as a “more granular” effort. He’s already urged employers to give workers paid time off to get vaccinated, with the federal government picking up the tab.

“There are millions of Americans who just need a little bit of encouragement to get the shot,” he said.

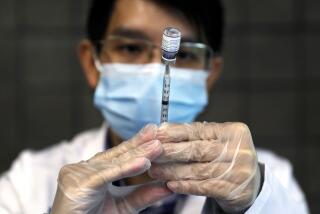

The president downplayed the slower pace of vaccinations, saying it was expected once the country had inoculated the most vulnerable and the most eager. More than two-thirds of Americans who are at least 65 years old are fully vaccinated, and more than half of adults have gotten at least one dose. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, which are the most commonly administered, require two shots.

But the struggle to break through many Americans’ vaccination hesitancy is apparent in the less ambitious target that Biden announced. He called for 70% of adults to receive at least one dose by July 4, and for 160 million adults to be fully vaccinated by that point.

To reach that goal, he wants an additional 100 million shots in arms in the next 60 days, a reduced pace after 220 million shots were administered in Biden’s first 100 days in office.

Moving into the yellow tier clears the way for Los Angeles County to unshackle its economy to the widest extent currently allowed.

Although Biden has been focused on July 4 as a milestone in the country’s emergence from the pandemic, he emphasized that the vaccination campaign will continue beyond then. For starters, the Food and Drug Administration could authorize the Pfizer vaccine for Americans as young as 12, he said, and his administration would “move immediately” to distribute the necessary doses. Right now it’s available for anyone at least 16 years old.

A senior administration official, who declined to speak on the record before Biden’s remarks, said young people who may not feel threatened by the coronavirus should still get vaccinated. “Even if you don’t get any symptoms, you are part of the chain of transmission, and you are propagating the outbreak,” the official said.

The goal, the official said, is to “box the virus in,” by eliminating opportunities for it to jump from person to person.

Widespread reluctance to getting vaccinated could make it difficult to end the pandemic, leaving the possibility that the coronavirus would continue to circulate even as it became easier to manage and protect against.

Robert J. Kim-Farley, an epidemiologist at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, said “herd immunity” could be defined two ways: “One is markedly reducing the number of cases and eliminating large outbreaks, and the other is eliminating the virus.”

“I don’t think we’ll catch the latter,” he said. “But we can catch the former.”

The federal inoculation campaign will try to sway holdouts throughout the year. The administration is pumping $250 million into community organizations to answer questions about vaccines and help arrange appointments to get shots, plus another $250 million to assist states, cities and territories. Vaccine education efforts in underserved communities will receive $130 million.

“There’s a lot of misinformation out there, but there’s one fact that I want every American to know,” Biden said. “People who are not fully vaccinated can still die every day from COVID-19. Look at the folks in your community who have gotten vaccinated and are getting back to living their lives, their full lives.”

Regional differences could become more stark in the coming weeks and months, reflecting how politicized the anti-pandemic measures have become. Republican-led states in the South have lower vaccination rates than Democratic-led states in the Northeast and the West, and some states aren’t ordering their full allotment of doses because of lower demand for shots among their residents.

The federal government will redistribute any doses that states don’t claim, another administration official said. The shift could either provide an incentive for lagging states to find ways to boost demand, or focus supplies on states where more residents are eager to get a shot, allowing the nation to keep up its inoculation pace.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.