Senate passes bill to counter hate crimes against Asian Americans

With a bipartisan vote, the Senate passes a bill that targets hate crimes against Asian Americans.

WASHINGTON — The Senate on Thursday approved a bill designed to make it easier for law enforcement to investigate hate crimes against Asian Americans after a surge in violence amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

In a rare, if fleeting, moment of bipartisanship on Capitol Hill, senators approved the bill 94 to 1.

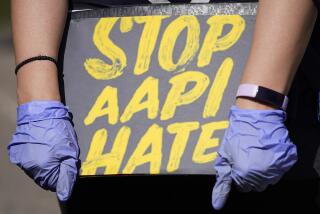

“We will send a powerful message of solidarity to the AAPI community that the Senate will not be a bystander as anti-Asian violence surges in our country,” Sen. Mazie Hirono (D-Hawaii) said before the vote, referring to Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

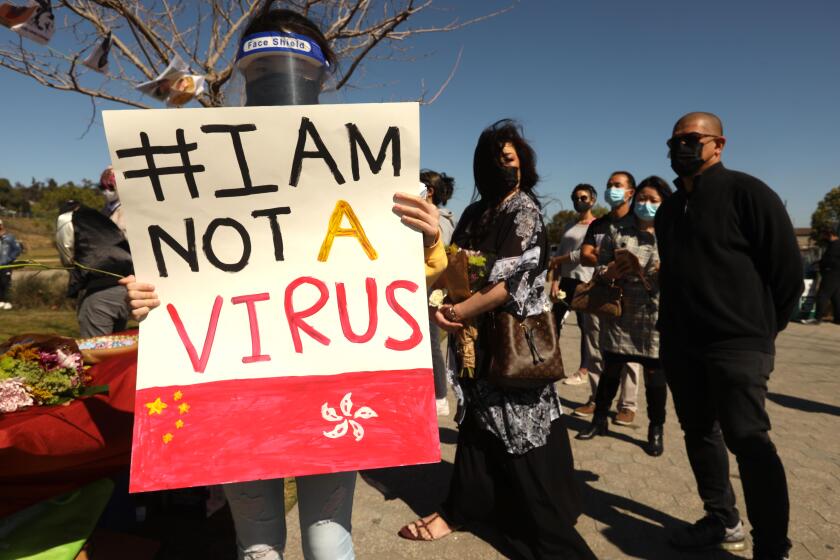

Hirono cited the more than 3,800 anti-Asian hate crimes reported around the country in the last year, according to research by Stop AAPI Hate. Days after Hirono introduced the bill last month, a gunman killed eight people, including six Asian women, in attacks at three spas in Georgia.

The bill would designate one Justice Department official to expedite review of potential hate crimes against Asian Americans. It would also set up a voluntary database of hate crimes and issue guidance to help local law enforcement make it easier for people to report crimes. And it would help local agencies develop public education campaigns on prevention and reporting of crimes.

“More reporting of hate crimes will provide us with increased data and a more accurate picture of the attacks that have been occurring against those of Asian descent,” said Rep. Grace Meng (D-N.Y.), who is leading the bill’s effort in the House. “And a more centralized and unified way of reviewing these crimes would help to address the problem in a more effective manner.”

Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D-Ill.), who is Thai American and worked on the bill with Hirono, said that her mother was recently harassed at a grocery store.

“This bill will allow me to go home and tell my mom we did something about it,” she said after the vote. “This tells the AAPI community, we see you, we will stand with you and we will protect you.”

Republican Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri, the only senator to vote against the bill, said it was “too broad.”

“As a former prosecutor,” he said, “my view is it’s dangerous to simply give the federal government open-ended authority to define a whole new class of federal hate crime incidents.”

The bill originally addressed only hate crimes related to the pandemic, a link that Republicans and others viewed as potentially too onerous for law enforcement to make. Hirono wanted the bill to highlight the role the pandemic — which was first reported in Wuhan, China — played in the increase in hate crimes. Former President Trump frequently called COVID-19 the “China virus” and the “Wuhan flu.” But Hirono agreed to drop the requirement in an amendment with Republican Sen. Susan Collins of Maine.

About 68% of the anti-Asian attacks documented during the pandemic were verbal harassment, 21% were shunning and 11% were physical assaults.

A bipartisan group of lawmakers also added a provision supporting local law enforcement agencies that use a new hate crime reporting tool and establishing grants for states to run hotlines.

The bill passed in a roll call vote but without a filibuster, an exceedingly rare situation in today’s Senate. More typically, for the last decade or so, legislation that gets through the chamber is either so uncontroversial that 100 senators approve it or so contentious that it must overcome the filibuster’s 60-vote threshold.

Overcoming a filibuster typically takes months of negotiation and is often only successful in emergencies, such as avoiding a national default on the debt or responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. This bill managed to find that elusive middle ground.

Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) pointed to Thursday’s vote as evidence the Senate could function, complete with amendments from both parties and no threat of a filibuster.

It is “proof that when the Senate is given an opportunity to work, the Senate can work to solve important issues,” he said.

But if anything, it showed that even the most basic, widely supported piece of legislation could still be difficult to get through the chamber.

As recently as last month, Democrats were daring Republicans to filibuster the legislation, suggesting that if they were willing to block a common-sense bill, they would filibuster anything.

Democrats allowed votes on three additional Republican amendments. All failed. Typically, as probably happened here, senators drop objections to allowing a bill to pass if they are able to get a vote on their amendment.

The bill now goes to the Democratic-controlled House. If approved there without changes, it would go to President Biden for his signature.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.