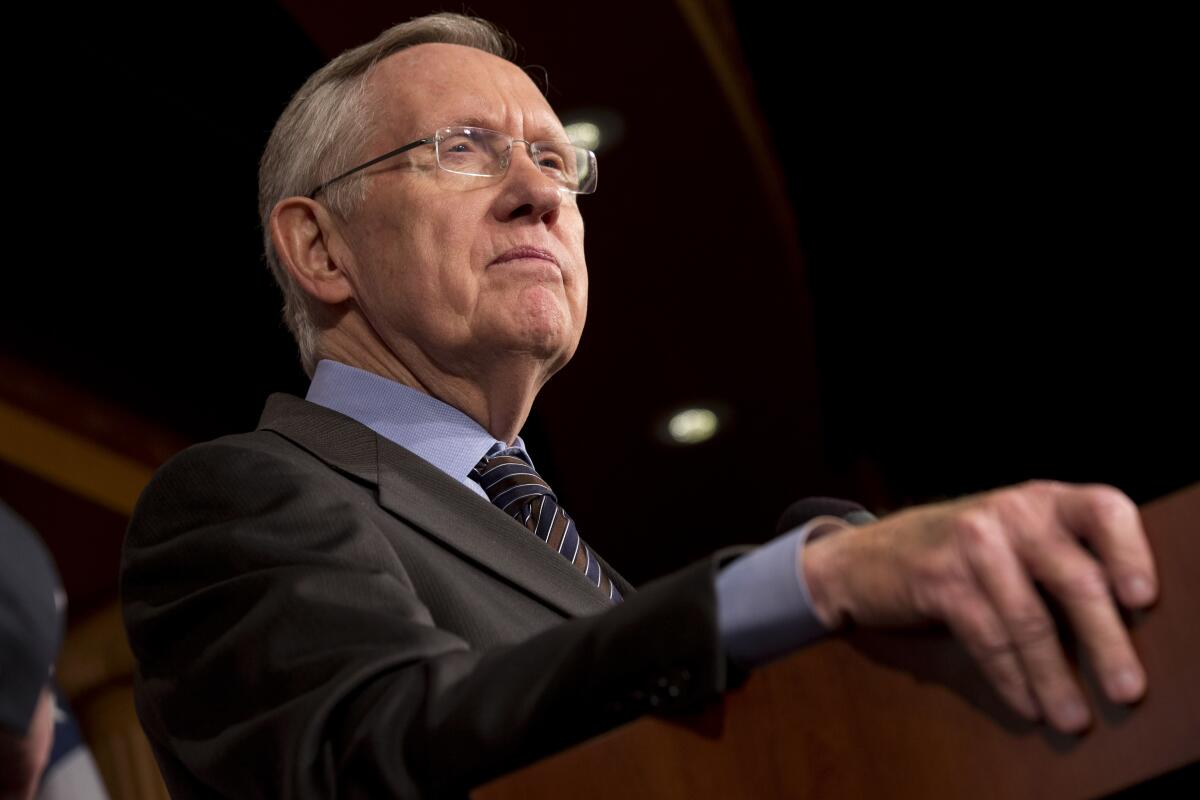

Column: Harry Reid made Nevada a presidential battleground. Now he wants more

When Harry Reid met Joe Biden it was 1987. Reid was new to the Senate and had a favor to ask the Judiciary Committee chairman.

“There was a Nevada person that had been nominated to be a federal judge and I didn’t want that person to be a federal judge,” Reid said.

He didn’t know Biden, but their conversation ended with an assurance. “You don’t want that person to be a judge,” Biden told him, “he won’t be a judge.”

Done.

For the next several decades, through Reid’s dozen years in the Senate leadership and Biden’s turn as vice president, the two kept up a mutually beneficial relationship.

Biden was Reid’s friend in the White House. Reid endorsed Biden for president and was instrumental this year in delivering Nevada’s six electoral votes.

Now, once again, Reid has a favor to ask: He’d like to elbow aside Iowa and New Hampshire, the states that go first and second in picking the nation’s president, and start the nominating process in Nevada.

“I think we’re entitled to be the first state,” Reid said in a Zoom call from his home in Henderson, just outside Las Vegas. “Why? Because the power structure of this country is moving West.”

With that, ever so matter-of-factly, the retired senator would upend 50 years of political practice and tradition.

For better or (many would argue) worse, Iowa and New Hampshire have benefited from a self-perpetuating cycle: White House hopefuls descend on the two states because they know they will attract news coverage by visiting, and the political press corps, in turn, focuses on Iowa and New Hampshire because that’s where the presidential candidates are.

Nothing about the nominating process is carved in stone — unlike, say, the injunction that all Iowa caucus stories mention corn or soybeans, and every New Hampshire primary piece must refer to the state’s voters as “flinty.”

The rules for the nominating process are set by the political parties. As head of his party, the president has a big say in determining those rules.

Biden and Reid have spoken a few times since the election, Reid said, but the president-elect has other concerns at the moment: staffing his incipient administration, addressing the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic fallout, ensuring the country remains a functioning democracy. That hasn’t stopped Reid, who remains a major power in Nevada, from lobbying people close to Biden and taking up his proposal with members of the Democratic National Committee, the party’s governing body.

(For his part, the 81-year-old Reid has his own priorities. While his pancreatic cancer is in remission, thanks to an experimental treatment, he continues to undergo regular chemo- and immunotherapies.)

I think we’re entitled to be the first state. Why? Because the power structure of this country is moving West.

— Former Nevada Sen. Harry Reid

As Senate majority leader, Reid played a key role in turning Nevada from an afterthought into one of the earliest presidential contests, placed third on the Democratic calendar starting in 2008. “Nevada’s caucus worked well,” he said of his handiwork, which coaxed presidential candidates to come seriously campaign in the West. “But its usefulness is on the way out.”

Indeed, Reid would like to end all caucuses and replace them with primaries, a sentiment widely shared among Democrats who believe primaries encourage greater participation and, thus, are more small-d democratic.

If ever Iowa was in danger of losing its privileged place on the political calendar it is now, after faulty software resulted in a February debacle that delayed caucus results for days. That followed counting controversies in 2012 and 2016 as well.

The greatest impediment to Reid’s Nevada-first vision appears to be New Hampshire, whose primary is eight days after Iowa’s caucuses.

State law requires that New Hampshire hold the nation’s first presidential primary and Secretary of State Bill Gardner, who could teach bulldogs a few things about tenacity, has made it his life’s work to ensure New Hampshire is never supplanted — even if that means the contest takes place in the fall ahead of a presidential election year.

“Message to Harry,” said Bob Mulholland, who spent nearly three decades as one of California’s representatives on the DNC. “Nevada will not be the first primary. You will always be after New Hampshire.”

Democrats are two years or so away from setting their nominating rules and establishing the calendar for 2024. There will be public hearings and private discussions and committee votes and more discussion and more hearings and on.

Reid, who knows a few things about negotiations and compromise, made clear he wouldn’t insist his state replace Iowa and New Hampshire if doing so risked Nevada’s current place on the calendar. “I’d love to be the first, but I’m not going to stab myself in the heart just hanging on to that if it can’t be done,” he said.

Still, he pointed out that Nevada — where Asian American, Black and Latino voters made up nearly a third of the November electorate — is far more ethnically diverse and representative of America than Iowa or New Hampshire, which are predominantly white and rural.

As it happens, that is precisely the argument Biden made explaining away his disastrous showing in the first two contests. He helped right his campaign with a second-place finish in Nevada and exulted, “We’re alive!”

“Y’all did it for me,” he told supporters in Las Vegas. “Now we’re going to go to South Carolina and win and take this back.”

Given that experience and his unhappy Iowa history — Biden also lost badly there in a 2008 try for the White House — it would seem the president-elect harbors little sentimental attachment to the place. Certainly his understudy, California Sen. Kamala Harris, wouldn’t mind terribly if the opening 2024 contest took place in next-door Nevada. (Though heaven forbid the vice president-elect appear to even think about her future political prospects.)

Reid faces no such restraint. Having Biden and Harris in his corner has crossed his mind, Reid allowed, and his usual poker face creased with a smile as he relished the political fight ahead.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.