Congressional leaders reach deal for nearly $900-billion coronavirus aid package

WASHINGTON — Congressional leaders agreed Sunday on a nearly $900-billion economic aid package to extend federal unemployment payments and forgivable loans for small businesses, and to give direct cash payments to many Americans.

The leaders — under increasing pressure from constituents and rank-and-file lawmakers, and confronted with both a slowing economy and surging coronavirus infections and related deaths — are racing to pass it into law before millions of Americans lose their financial lifeline. The final text of the aid package, the second-largest in U.S. history, was expected to become available Sunday evening or Monday morning, leaving members of Congress little time to review it before voting .

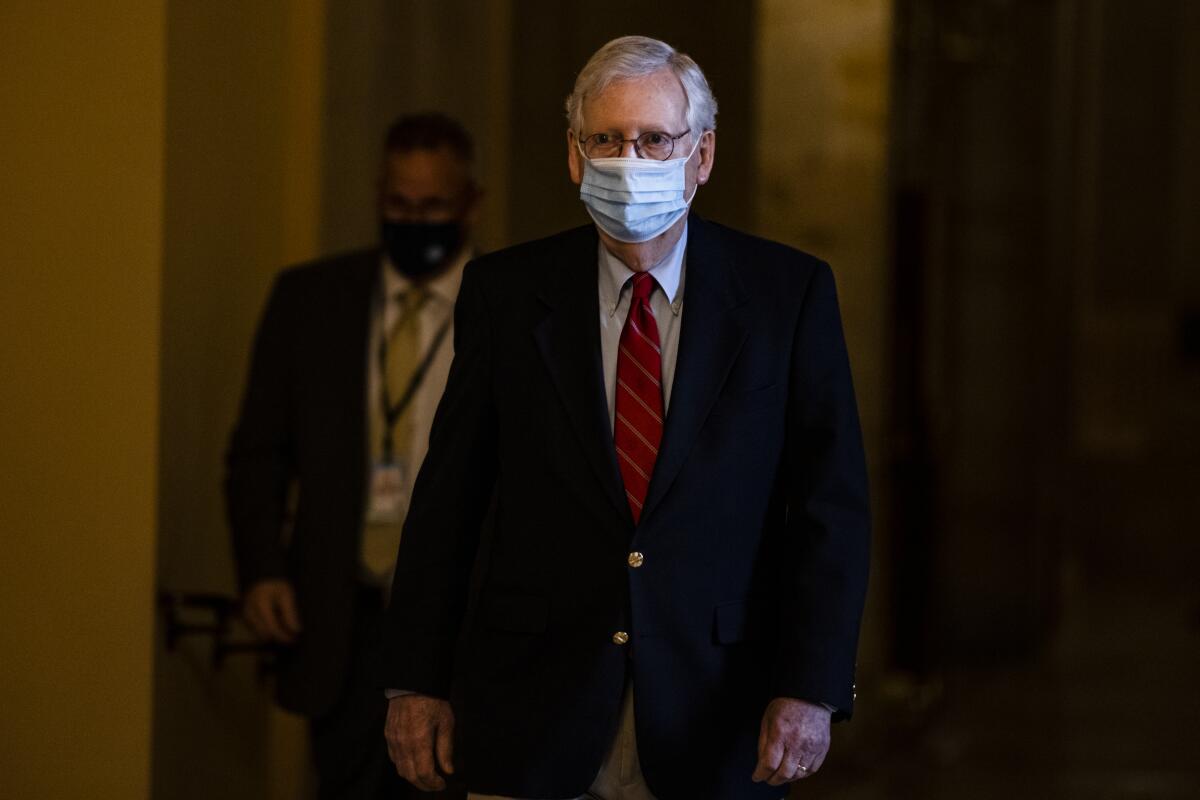

“We can finally report what our nation has needed to hear for a very long time. More help is on the way,” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said on the Senate floor.

The bipartisan deal crafted by the top four congressional leaders must be passed by the House and Senate and signed by President Trump to become law. The additional federal unemployment aid created by Congress in March in the so-called CARES Act expires Saturday, and most other benefits lapse before the end of the year.

The House will vote on the bill Monday, Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D-Md.) announced. The Senate is expected to follow soon after.

“Finally, we have some good news to deliver to the American people. Make no mistake about it, this agreement is far from perfect, but it will deliver emergency relief to a nation in the throes of a genuine emergency,” Senate Minority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) said.

Congressional leaders plan to attach the aid to a must-pass $1.4-trillion package to fund the operations of federal agencies through the fiscal year ending Sept. 30. Congress has passed several short-term resolutions to extend the funding and keep the government open while the aid package was being negotiated. They are expected to pass a one-day extension to keep the government open until the massive package can be approved.

While Trump has not been involved in the talks, Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin has played a role, and the president is expected to support a deal that has Republican leaders’ backing.

According to senators and representatives, the package would allow 11 additional weeks of compensation for jobless Americans, and also add $300 a week from the federal government to the amount they receive through their state unemployment program. That is half of the $600 a week they received from March through July under the CARES Act. It also extends for 11 weeks an unemployment benefits program for contract and gig workers, which is set to expire at the end of the year.

The maximum weekly unemployment insurance payout in California is $450, so until the federal benefit runs out again March 14 the most an unemployed person in California could get is $750 a week.

The package would also provide a one-time direct payment of up to $600 to Americans making less than $75,000, half the maximum $1,200 distributed in the spring. The amount of the payment would gradually diminish based on income, starting with those who earned more than $75,000 in the 2019 tax year. Those who earned more than $99,000 would receive nothing. Children are eligible for $600. Adult dependents would not qualify, but unlike in the spring mixed legal status families would be eligible.

It includes $284 billion for another round of Paycheck Protection Program loans for small businesses, with some set aside specifically for very small and minority-owned businesses that didn’t get an equitable share of the original loans. It also allows nonprofits and religious institutions to apply for the loans. The deal also contains billions for vaccine production and distribution, $13 billion for food assistance, $25 billion for rent payment assistance, $10 billion for child care assistance and $82 billion for schools, colleges and universities.

There is money for transit systems struggling with a drop in ridership and for entertainment venues, and the measure continues the moratorium on evictions from properties where the mortgage is held by the federal government.

For eight months, members of Congress have talked about the need for another economic aid package to help struggling Americans. They have pointed fingers at the opposing party as the reason it wasn’t possible but failed to move legislation as unemployment rates rose and millions of Americans got sick and hundreds of thousands have died. The acrimony led some lawmakers to declare in mid-November that there was little chance Congress could pass another package.

Negotiations on the aid package resumed in earnest earlier in the week at the prompting of a bipartisan group of senators and representatives. The talks gained speed after Republican and Democratic leaders agreed to drop the two main sticking points — aid for state and local governments, which House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) and other Democrats wanted, and a provision shielding businesses from liability in lawsuits related to COVID-19, a priority of Republicans and in particular McConnell.

The package does not provide new money for state and local governments, but it gives them an extra year to spend their share of the $150 billion provided in the CARES Act.

Most issues had been resolved by Friday, but negotiations dragged into the weekend as senators argued over whether Congress should rein in the Federal Reserve’s emergency lending powers.

Sen. Patrick J. Toomey (R-Pa.) pushed for a provision that would have shut down a Fed lending program that helped prop up state budgets and corporations during the pandemic, and it would have prevented the Fed from restarting such an effort without congressional approval. Democrats pushed back, saying Toomey’s proposal would have tied the hands of future administrations, including the incoming Biden administration, in moments of crisis. The Federal Reserve has had the authority to take such actions since the Great Depression, though it is rarely used.

Toomey and Schumer ultimately reached a tentative solution late Saturday, dropping language saying the Fed chair couldn’t create similar programs in the future. The existing programs would still end.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.