Biden urges pandemic relief compromise, testing his faith in bipartisanship

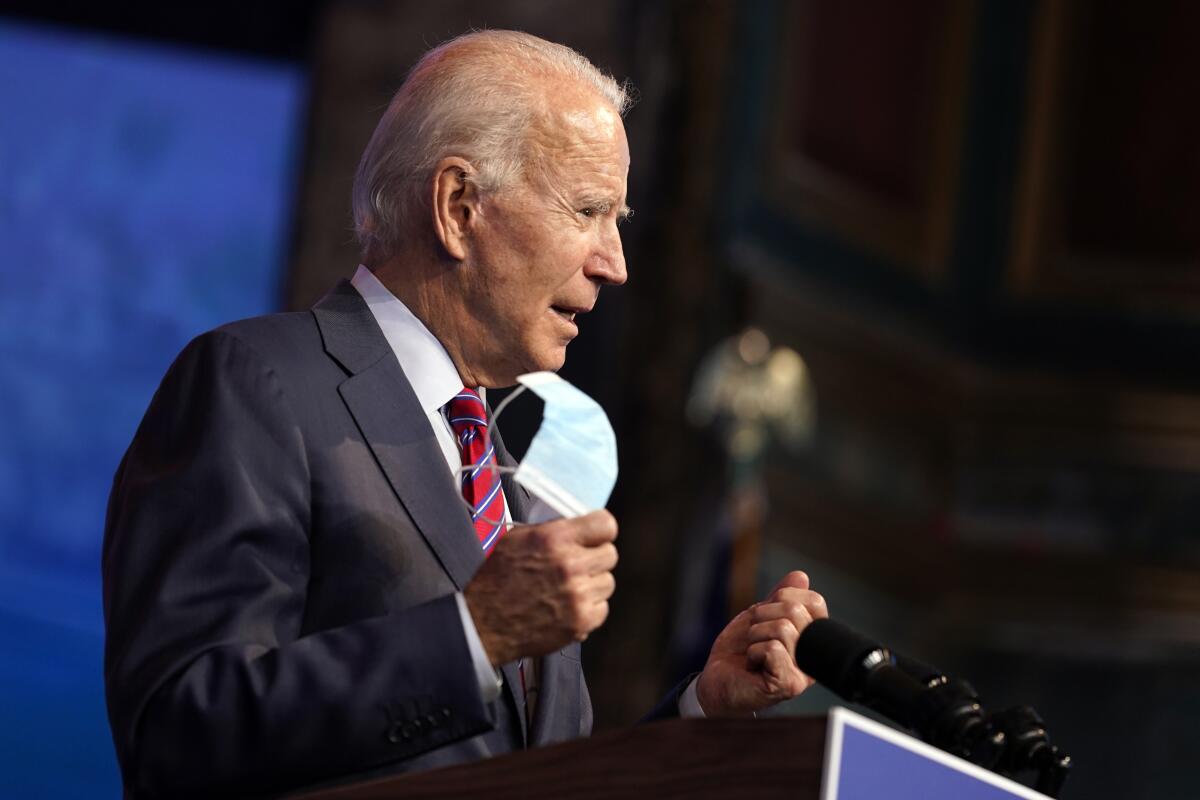

WASHINGTON — President-elect Joe Biden is trying to help break a months-long deadlock in Congress over a new installment of pandemic relief, testing his aspiration to preside over a new era of bipartisan cooperation in Washington, even before he takes office.

Biden seized Friday on a grim new report on unemployment to amplify his call for Congress to act on a bipartisan $900-billion relief bill that emerged this week — half the size of a package that Democrats wanted but twice as much as Republicans have proposed.

“If we don’t act now, the future will be very bleak,” Biden said, speaking to reporters in Wilmington, Del. “Americans need help and they need it now, and they’ll need more to come early next year. But I must tell you, I am encouraged by the bipartisan efforts in the Senate around a $900-billion package of relief.”

His call for action during the lame-duck session of Congress comes as the government’s latest unemployment data for November and a rising COVID-19 death count made clear this sobering prospect: Biden’s presidency will begin amid a national crisis far more dire than even the one that he and President Obama inherited 12 years ago in January 2009, which was the worst recession and financial collapse since the Great Depression.

Biden’s Friday remarks were the latest and perhaps most prominent example of how the president-elect, more than a month before his swearing-in on Jan. 20, has tried to get a jump on his health and economic policies and to fill the leadership vacuum that Trump has left while pursuing vain efforts to reverse his election defeat.

America’s employers scaled back their hiring last month as the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated across the country.

Arguing that the economy can’t be fixed until the coronavirus is vanquished, Biden said he will ask all Americans to wear masks during his first 100 days in office. He will require masking in all federal buildings and on modes of interstate transportation including airplanes and buses. Biden asked Dr. Anthony Fauci to stay on as his top medical advisor, fortifying his health team with the nation’s most renowned infectious-disease fighter.

During the 2020 campaign, Biden made a point of touting his experience in coping with economic calamity, citing his role as Obama’s vice president in getting Congress to pass a nearly $787-billion economic stimulus plan and then in overseeing its implementation. In assembling his economic team this week, Biden turned to many past advisors who also were with him in the policy trenches during the recession and recovery through Obama’s first term.

That crisis-tested team now faces a bigger challenge as they tackle an economy greatly weakened by the worldwide pandemic.

In an interview Thursday on CNN, Biden compared this time to 1932, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected president amid the Depression, as well as to the period of economic hardship that confronted Obama.

“There are so many things that are going to land on this president’s desk, me in this case,” he said. “As I said about Barack, everything but locusts is going to land on this. We have significant problems.”

Friday’s unemployment report showed that job growth slowed dramatically in November and more people gave up looking for work. It also showed that employers added only 245,000 jobs last month — down from 610,000 in October. That was the latest sign that the country is caught between the surging COVID-19 outbreak and the race to deploy an effective vaccine on an unprecedented scale.

Skyrocketing hospitalizations and record deaths from the coronavirus have sparked new fears of another recession and deepening pain for millions of people whose unemployment benefits are expiring this month. Congress and the White House agreed to more than $3 trillion in aid for individuals and businesses in the spring, but much of that has run out.

Efforts to pass another installment of pandemic relief — unemployment assistance, aid to state and local governments, protections against eviction and more — have stalled for months in Congress in a partisan standoff. Trump has largely been a nonplayer; his Treasury secretary negotiated with Democrats, but only angered Republicans in so doing. But pressure to act has mounted in the face of the infection surge and weakening economy, and because several forms of assistance are due to expire Dec. 31.

Democrats and Republicans say they’re hopeful they can pass an economic relief bill, but it’s far from certain their optimism will lead to aid for millions of Americans.

After initially staying on the sidelines of the negotiations, Biden this week contributed to the gathering momentum for the lame-duck Congress to act. He joined Democratic leaders in backing, at least as a starting point, the $900-billion compromise proposed by a bipartisan group of lawmakers.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) said Biden was key to her willingness to change course and back down from her long-standing demand for a much bigger package. She showed new confidence that more money would be approved next year, given Biden’s election, and she hailed the progress in vaccine development.

“That is a total game-changer — a new president and a vaccine,” Pelosi said at a Friday news conference. “We have a new president — a president who recognizes that we need to depend on science to stop the virus.”

It is far from certain that Democrats’ concession will be met with flexibility from Republicans. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has not publicly moved off his $500-billion proposal, but he did say Thursday, “Compromise is within reach.”

Biden and McConnell have a history of working together in big legislative negotiations, when Biden was vice president. But the two men in the weeks since the election have not talked, both have said, and McConnell has not publicly acknowledged Biden’s victory. On Friday, however, Biden twice dodged questions about whether he had talked to the Republican leader.

Predictably, Biden’s call for compromise has put him at odds with his most formidable Democratic presidential primary opponent, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, a political independent and leader of the Democratic Party’s emboldened left. Sanders said Friday he would oppose the bipartisan proposal unless it was “significantly improved” to provide more aid to workers.

Biden has said, however, that he sees the pending compromise as just a down payment on a bigger investment he hopes to pass next year. “To truly end this crisis, Congress will need to fund more testing, as well as a more equitable and free distribution of the vaccine,” he said. “We need more economic relief to bridge through 2021.”

Biden’s optimism about working with Republicans was central to his campaign message. But it was derided by many fellow Democrats as naive and unrealistic in a capital that has become more deeply polarized in the years since Biden left the Senate in 2009 — and even since he left the vice presidency in 2017.

In encouraging those in Congress to reach a compromise this month, Biden aims to prove the doubters wrong.

“You know, in the weeks since the election ended, there were questions about whether Democrats and Republicans could work together,” he said Friday. “I know many of you are skeptical about my view that they will and they can. Right now, they are showing they can.”

Times staff writers Don Lee and Sarah D. Wire in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.