MARIETTA, Ga. — Standing on the bed of a pickup truck, the Rev. Raphael Warnock told hundreds of cheering Democrats on Sunday that Georgia was positioned to do a “marvelous” thing: send the Jewish son of immigrants and a Black pastor reared in a Savannah housing project to the U.S. Senate at the same time.

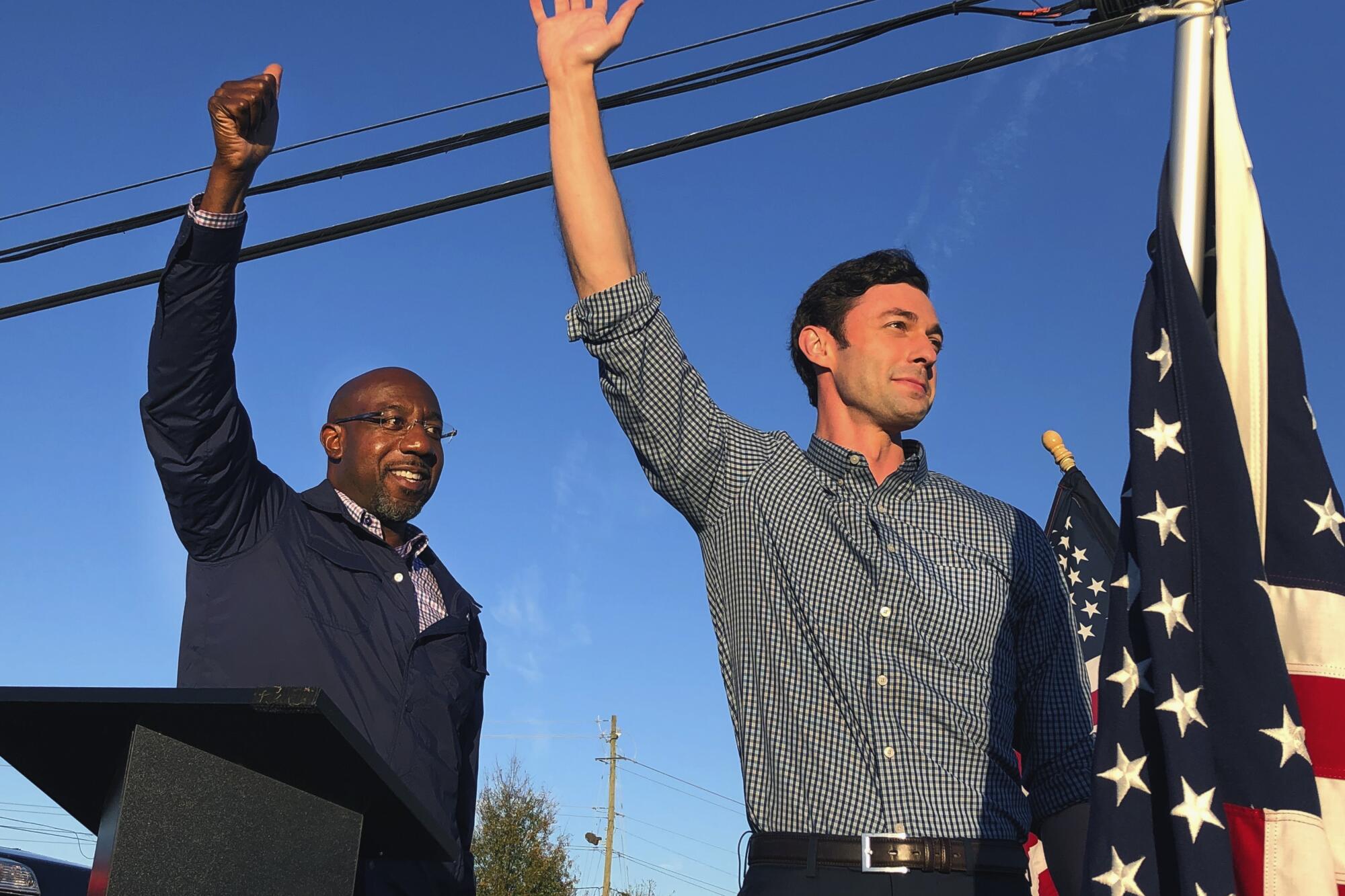

“This is what America is about,” Warnock said as he joined fellow Democratic Senate candidate Jon Ossoff at a campaign rally in Marietta. “We can lift all of us out of this darkness into a new daybreak of freedom and prosperity for this great country. We can do it — but the only way to do it is together.”

As a rare duo runoff election for two Senate seats unfolds in Georgia, Warnock and Ossoff have essentially become running mates, their fates tied together as they try to persuade voters to send them — not the two Republican incumbent Sens. David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler — to Washington.

Both Republican and Democratic camps have embraced running as teams, holding joint events and framing their stump speeches around what they could accomplish — or stop — together in Washington.

“I win, she wins; she wins, I win. It’s as simple as this,” Perdue said Friday as he and Loeffler linked up at a packed indoor rally in Cumming, Ga. “Kelly and I are asking you to stand with us!”

Campaigning as a ticket has clear advantages and efficiencies in a statewide race, particularly during a pandemic. It can also serve to bolster and balance candidates’ resumes. Warnock, for example, could help Ossoff appeal to Black voters, while Perdue’s experience lifts relative newcomer Loeffler.

It’s not the first time Senate candidates from the same state have run as a dynamic duo. In 1992, Dianne Feinstein referred to herself and fellow Democratic candidate Barbara Boxer as “Thelma and Louise.”

But there are risks as well to linking fates. If one candidate goes down, so likely does the other. That could be a problem, particularly for Republicans, who only need to win one of the Georgia seats to maintain control of the Senate, and to be able to block President-elect Joe Biden’s agenda.

The joint campaigning strategy also reflects the nationalization of the Jan. 5 special election, which is already less about the candidates’ individual records and back stories, and more about which political party will control Washington in the coming years.

For Democrats to have any hope of advancing Biden’s policies in Congress, they will need to win both Senate seats in Georgia, resulting in a 50-50 tie that Kamala Harris could break as vice president.

“This is a shirts-versus-skins, Democrats-versus-Republicans, who-can-turn-out-the-most-people election,” said Brendan Buck, a Republican strategist and Georgia native. “The nuances of your campaign are a little less important in that way — it’s all base motivation.”

Democrats are positioning Ossoff and Warnock as emblems of the party’s diversity, a combination that is perhaps stronger together.

They hope Ossoff, a 33-year-old Jewish documentary producer who grew up in the Atlanta suburbs, can appeal to a new generation of young, educated suburban voters, while Warnock, 51, the longtime pastor of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, is popular with the party’s traditional Black base.

On the Republican side, the pairing is less about contrast. Perdue is a wealthy 70-year-old businessman who has served as the senior senator for Georgia since 2015. Loeffler, 49, is a fellow multimillionaire and former chief executive of a financial services company. They argue that a GOP Senate is the only thing that can serve as a meaningful check on Biden and Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco).

“Make no mistake: We are the firewall — not just for the U.S. Senate, but the future of our country,” Loeffler said Friday in Cumming.

Both Republicans have been strong supporters of President Trump, a factor that could prove important if the president gets involved in campaigning.

Democrats are hoping to take advantage of the joint campaigning by Loeffler and Perdue to portray both as out of touch, particularly when it comes to the Senate’s failure to enact a new round of coronavirus relief. That’s a message that could resonate with voters since both Republicans were found to have traded stocks to protect their investments as the pandemic raged. Both say the stocks were traded by financial advisors without their knowledge.

“Usually, when you’re running as a ticket, everyone brings something to the table,” said Jen Jordan, a Democratic state senator who represents parts of northern Atlanta. “But for the two Republicans, they’re basically two sides of the same coin.… They may be a different gender, but they both have houses on Sea Island behind a locked gate that the public can’t get to. They are multi-multimillionaires, both of them. They’re completely disconnected from what average Georgians go through.”

But their Democratic rivals face vulnerabilities as well. Republicans are painting both as too progressive for Georgia, falsely labeling Ossoff and Warnock as “socialists” who embrace policies such as defunding the police. They also hope to drag down Ossoff by linking him to the most liberal aspects of Warnock’s biography.

Warnock has faced heat for his prior support of the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, President Obama’s controversial former pastor, and for his past comments critical of Israeli policy in the West Bank. Last week, Loeffler cast Warnock as a radical who subscribes to a “Marxist ideology,” accusing him of “welcoming” Cuban leader Fidel Castro to a New York City church in the 1990s. Warnock served as a youth pastor at the church, but he has said he was not involved in the decisions about who spoke there, and never met Castro.

In the same way, Loeffler could prove to be a drag on Perdue, who has had six years to build a brand in Georgia. Loeffler entered the race as a moderate conservative who could appeal to suburban women. But during her fierce battle against other Republicans to make the runoff, she veered to the right, pitching herself as “more conservative than Attila the Hun.”

Even so, she has yet to win over some conservative voters.

Debbie Dooley, a Trump supporter and one of the founders of the tea party movement, supported GOP Rep. Doug Collins during the primary. Now she’ll support Loeffler, but warned that some Republicans will not.

“Them running as a tag team benefits Loeffler and it hurts Perdue,” Dooley said.

“Senators don’t run on a ticket,” she said. “And I think that there’s a danger in doing that, whether it’s Republican or Democrat, because usually when you run as a tag team like that it benefits the weaker candidate and it doesn’t benefit the stronger candidate as much.”

Special elections are decided by which party can turn out more voters, because only the most loyal party faithful typically vote. In this case, both sides agree that the two candidates of each party will most likely win or lose together. With little time to shape individual narratives and with none of the candidates proving particularly more compelling than their partner, there will be few, if any, voters who split their tickets.

“Both sides see that the best thing they can do is try to help each candidate pull each candidate across the finish line,” said Jason M. Shepherd, chairman of the Republican Party in suburban Cobb County, a former GOP stronghold 20 miles northwest of Atlanta that has tilted blue in recent years.

It is also a pragmatic way to activate voters and reinforce the message amid a global pandemic and a flurry of seasonal celebrations, including Thanksgiving, Hanukkah, Christmas and New Year’s — not to mention college football playoffs.

State Rep. Erick Allen, a Democrat representing the Atlanta suburb of Smyrna, said the Democratic and Republican campaigns were not running on the same ticket so much as realizing that they could probably mobilize more turnout by organizing joint events.

“In the world of COVID, the opportunity to get that many people out at one event is far and few between,” he said.

Whether or not the candidates linked up, Allen added, they would be associated with each other.

“Right now, everything is so partisan, people are really just electing a generic D and a generic R. So I don’t think there’s any more risk,” he said. “It’s very difficult for any candidate to escape the label that’s put on the generic R and D, so Perdue almost has to embrace everything that Loeffler is doing, because people are going to view them as the same Republican ticket.”

After an enormously expensive general election, there is a financial incentive, too.

“Co-branding under the party banners for both of the candidates is going to help both sides spend money as they try to replenish war chests,” Shepherd said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.