After four years of upheaval, election day gives voters their say

After a campaign of enormous consequence — waged amid a deadly pandemic, an economic collapse and a raw debate over race and justice — Americans on Tuesday will render their verdict on the most divisive and tumultuous four years in modern history.

At bottom, the contest amounts to a referendum on President Trump, his provocative behavior and the upheaval that has turned off more than half the country, polls show, while delighting supporters who welcome the shock to the political system.

“We could say it’s the pandemic, it’s the economic crash, it’s racial justice, it’s a Supreme Court nomination just days before an election,” said Amy Walter, an analyst for the nonpartisan Cook Political Report, ticking off seismic events of the last year, which also included Trump’s impeachment for pressuring Ukraine to dig up dirt on Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden.

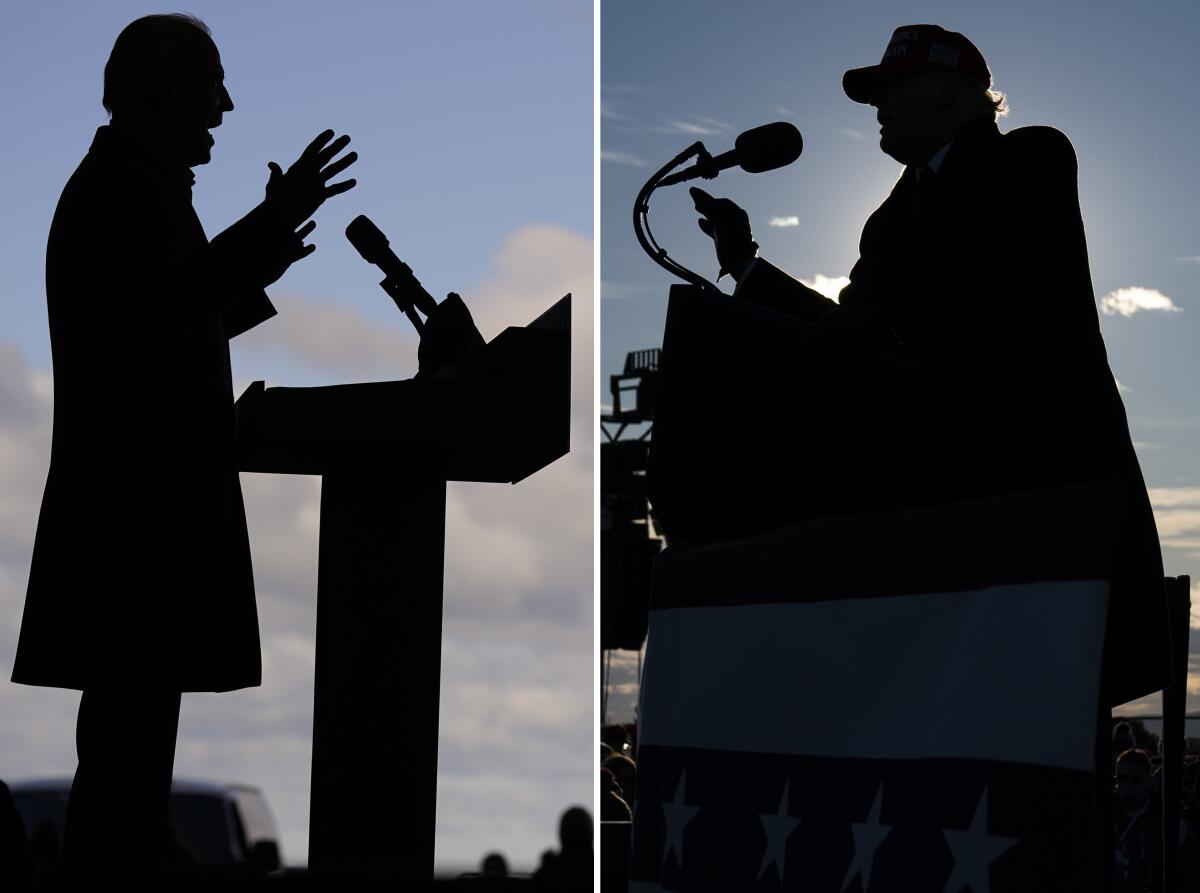

Photos: Election day voting is over but the counting continues.

“All of those things have had an impact,” Walter said. “But at its core, this election is about the same thing ... which is Donald Trump and your opinion of him.”

Voter interest has been extraordinarily high.

More than 100 million Americans have cast ballots even before polling places open on election day, surpassing 70% of all the votes counted in 2016.

Tens of millions more were expected to brave long waits and the risk of COVID-19 to vote in person on election day; experts projected overall turnout could top a record 160 million.

President Trump unfurled bitter grievances — including complaints about polls — while Joe Biden vowed ‘an end to a presidency that’s divided this nation.’

Polls have consistently given Biden the lead nationwide and in most battleground states, but there was enough uncertainty to leave the election outcome in doubt. With anticipated delays in counting ballots and Trump threatening to go to court to contest the result, it was not even clear how soon a winner will be declared.

It is not unusual for a presidential race to be decided after election day. That has happened half a dozen times since 1960, including four years ago when Trump’s victory did not become apparent until Wednesday morning on the East Coast.

Along with the White House, control of the Senate is up for grabs Tuesday, with Democrats hoping a pro-Biden wave could deliver the three seats they need to win a majority. (The vice president breaks ties, meaning Democrats would need to win four seats if Trump is reelected.)

With a huge financial advantage — part of an unprecedented gusher of money that has poured in for both parties — Democrats were also counting on adding to their ranks in the House, which they captured in a 2018 midterm backlash against Trump.

There is also history on Tuesday’s ballot: Biden’s running mate, California Sen. Kamala Harris, is bidding to become the nation’s first female vice president.

On Monday, Trump and Biden raced through a handful of battleground states, delivering their final pitch. The contest held true to its churlish form, with the candidates and their supporters slinging accusations, hurling invective and painting a dire portrait should the other side prevail.

For once the familiar line about this being the most important election of a lifetime didn’t seem hackneyed or contrived.

The COVID-19 pandemic has killed more than 231,000 Americans and is raging anew, with hospitals in cities across the country nearing capacity. The economy tanked in the spring when parts of the country locked down, with more than 14 million people losing their jobs before the economy partly bounced back.

The death of George Floyd while in Minneapolis police custody on Memorial Day sparked a wave of demonstrations and a torrent of racially charged rhetoric from Trump assailing the protests.

Trump has never surpassed 50% approval in credible opinion polls, which has often spelled doom for an incumbent. If reelected, he would be the only president in history to win a second term after being impeached.

Rather than seeking to broaden his appeal, Trump has rested his strategy on energizing an unwavering base of support among mostly white, working-class voters and coaxing millions of additional sympathizers to vote after staying home four years ago.

He has convinced Don Hunjadi, who lives in Norway, a suburb of Milwaukee.

The 57-year-old retired firefighter didn’t vote for the president or any other White House hopeful in 2016. But Trump “surprised the heck out of me,” he said.

“The stock market went to all-time highs, we were at historic lows for unemployment,” Hunjadi said, pausing outside a supermarket on a brisk and windy afternoon. “Anybody who wanted a job could have a job. He got the Supreme Court justices he wanted. I can’t complain about anything he has done.”

Not even, Hunjadi said, Trump’s handling of COVID-19.

The deadly pandemic has resulted in perhaps the sharpest divide of the campaign, in both word and deed.

Biden spent months sheltering at home, keeping safe from the virus. When he finally ventured out, he wore a mask and staged socially distanced rallies to avoid spreading the disease.

Trump continually minimized the infectious disease, saying that it would simply fade away and that the spike in cases was a result of increased testing. He mocked Biden and disdained masks and other protective measures.

Even after being hospitalized last month with COVID-19, he shrugged off its effects and traveled the country for a series of crowded, mostly mask-less events that put communities at risk.

Campaigning Monday across four states, Trump offered a familiar mix of grievance — including efforts to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the election — and promises of better times ahead, starting with a robust economic recovery and an imminent vaccine against COVID-19.

“Next year will be the greatest economic year in the history of our country,” Trump pledged at a stop in Fayetteville, N.C.

As usual, this presidential contest has come down to a narrow band of states.

The outcome in most places can be taken for granted — California voting for Biden; Mississippi, Alabama and others in the Deep South supporting Trump — which left a handful of familiar battlegrounds, such as Florida, Nevada and North Carolina, as the focus of both candidates.

Several other states also swung into play this election, foremost among them Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, which were longtime Democratic bastions until Trump eked out victories four years ago. This time, Trump is on the defensive in all three, as well as states including Arizona, Georgia and Texas that Republicans typically take for granted.

Part of that is a reflection of the president’s weak political standing. But it is also attributable to Biden, a far less polarizing figure than Hillary Clinton was in 2016.

Election 2020: These states will probably decide if Joe Biden or President Trump wins the race. And their absentee ballot laws could determine when we find out.

The former vice president began the year seeming destined to lose the Democratic primary. Desperate for money and drawing cringingly small crowds, he finished fourth in the opening contest in Iowa and fifth the following week in New Hampshire.

But his fortunes turned around with stunning rapidity after Biden won the South Carolina primary 14 days later. Within 72 hours, two of his major rivals dropped out and the party soon coalesced around Biden’s candidacy.

It was right around then, in mid-March, that the novel coronavirus went from being a vague concern to a menace that has turned lives upside down. The pandemic robbed Trump of his greatest political asset — a strong economy — and made all other issues pale in comparison.

“Everything is driven by the virus,” said Liesl Hickey, a Republican strategist whose specialty is suburban voters. “It’s been the No. 1 issue since it emerged and it continues to be the No. 1 issue.”

The toll has been central to Biden’s strategy of portraying Trump as a feckless, uncaring leader.

Voting news from around the country

On Monday, he savaged the president for claiming that doctors were inflating COVID deaths so they could make more money, calling Trump a “disgrace.” He also scoffed at the president’s suggestion that he would fire Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert.

“Elect me and we’re gonna hire Dr. Fauci,” he told the cheering crowd in Cleveland. “And we’re gonna fire Donald Trump!”

For Dennis Roberts, the pandemic is just the tip of his aggrievement with the president.

“I think that we stand on the brink of utter chaos,” said the 66-year-old retired social worker in Philadelphia. “I believe that four more years of Trump would be devastating socially, economically, medically, and I think that he has been perhaps the most divisive leader that the U.S. has had.”

As Roberts spoke downtown, crews were nailing plywood onto storefront windows in anticipation of violence once the election returns start rolling in.

This campaign has torn apart the country like nothing since the Vietnam War era. If there is one unifying force, it may be relief it’s almost over.

“There’s 2020 fatigue. There’s COVID fatigue. There’s election fatigue,” said David Kochel, a Republican strategist who has been critical of the president. “A number of people want to turn the page, no matter what side they’re on.”

Times staff writers Michael Finnegan in Philadelphia, Melanie Mason in Cleveland and James Rainey in Milwaukee contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.