Is the election over when it’s over? Fears Trump vs. Biden could go into overtime

The most costly and contentious presidential campaign in modern history is winding to an ominous close, with no certainty its hostilities will end on election day.

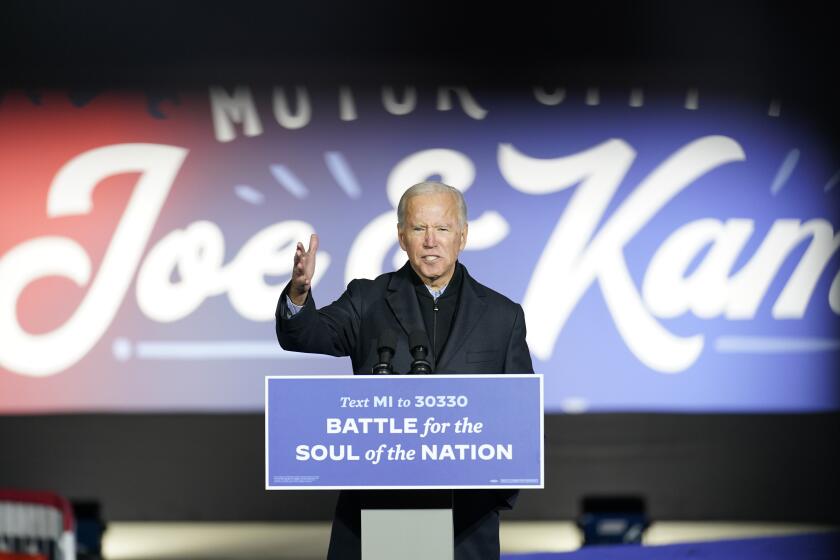

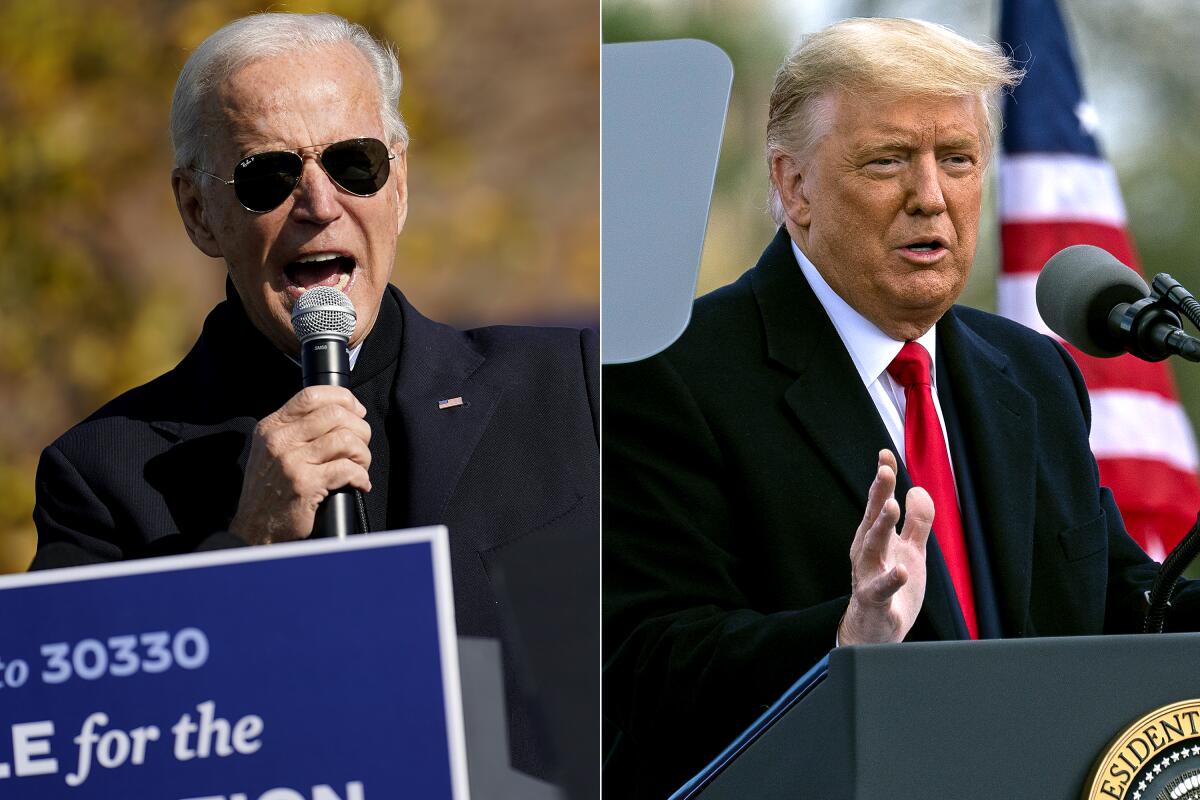

Democrat Joe Biden, making his third try for president, holds a steady lead in polls, both nationally and in enough states to secure the 270 electoral votes needed to win the White House.

His huge financial advantage over President Trump — Biden entered October with $117 million more in the bank — and Trump’s handling of the pandemic have allowed the former vice president to drive deep into traditionally Republican territory. Arizona, Georgia and even Texas, which hasn’t supported a Democrat for president in more than 40 years, are in play.

But memories of 2016, when Hillary Clinton was ahead and even Trump expected to lose, have banished any thoughts that the contest is over, buoying the president and his supporters, who remain convinced history will be repeated.

“A big red wave has formed,” Trump told reporters Saturday before a day of campaigning across Pennsylvania. “We’re doing very well.”

That determined bullishness, however, defies most empirical evidence, which suggests not just an uphill fight to win reelection but also a struggle to hang onto Republicans’ narrow majority in the Senate and avoid significant losses in the House.

Biden campaigns in Michigan with Obama, and Trump rallies in Pennsylvania, cheering a pro-Trump caravan surrounding and harassing a Biden bus in Texas.

All the concerns over conflict and upheaval could be moot if Biden were to win Tuesday in an electoral college landslide.

But a blizzard of preelection lawsuits challenging who can vote and how ballots are counted — the latest targeting 100,000 early votes in Democratic-leaning Harris County, Texas — and Trump’s refusal to unreservedly say he will accept an unfavorable outcome add to the tensions suffusing what has been a notably vicious campaign.

The vitriol was on display once more on Saturday, as the two candidates battled in Pennsylvania and Michigan, Trump reaching for an upset and Biden seeking to corral a congressional majority that could bolster his calls for change.

The president continued to downplay the COVID-19 pandemic, which has killed more than 230,000 Americans, suggesting that Biden poses the greater threat. Hurling insults, he claimed without basis that his rival would “lock down America” to gain “power and control over you.” (Later, the president approvingly tweeted a video of a caravan of supporters on a Texas highway swarming a Biden campaign bus.)

Biden, stumping alongside former President Obama, was scathing in response to Trump’s blithe statements regarding the pandemic.

“What in the hell is wrong with this man?” he said before a predominantly Black audience in Flint, Mich. “It’s a disgrace, especially coming from a president who’s waving the white flag of surrender to this virus.”

Set against a backdrop of deadly disease, economic contraction and a reckoning over racial injustice, this election was already extraordinarily important in terms of who wins the White House.

Heightening the stakes is the battle for control of the Senate and a series of legislative skirmishes across the country that will help determine how congressional districts are drawn for the next decade, an important consideration in who controls the House.

Democrats need to gain three seats on Tuesday to win the Senate majority if Biden takes the White House and four if he doesn’t. (The vice president serves as tie-breaker.) Nine Republican incumbents are at varying degrees of risk while just one Democrat, Alabama Sen. Doug Jones, appears to be in serious peril.

Trump’s struggles have created headwinds for the GOP in Arizona, Colorado, Iowa, Maine, North Carolina and Texas. Democrats have a reasonable shot at Senate seats in Kansas, Montana and South Carolina, Republican strongholds where polls give Trump a slimmer-than-normal lead.

At his drive-in-style rally in Flint, Biden used unusually stark language as he called for the reelection of Michigan’s Democratic Sen. Gary Peters.

“We have such an incredible opportunity, but here’s the deal, guys: We’ve got to vote up and down the ticket,” Biden said, as car horns blared in accord. “We have a chance to make such enormous progress because the American people have seen what the other side looks like. They’ve gotten a glimpse of the abyss.”

Measured in money and motivation, many voters apparently share Biden’s urgent view, if not necessarily his prescription.

This has become the costliest election in the country’s history, with spending expected to reach $14 billion, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, which tracks money in politics. The race for the White House alone is expected to cost $6.6 billion — more than the combined spending on the 2016 presidential race and every congressional campaign that year combined.

For anyone in range of a screen or a speaker, that has meant an inescapable onslaught of campaign advertising.

A viewer up early Saturday in Philadelphia woke to a flood of ads from Biden and his supporters, including instructions on how to vote, an outline of Biden’s plan to fight COVID-19 and a biographical spot narrated by Obama. Pro-Trump ads were fewer in number, but an ad paid for by drugmakers, hospitals and insurance companies made the case for the president’s reelection by attacking a healthcare plan Biden supports.

In central Florida — a key battleground in the county’s most populous swing state — appeals poured from radios in English and Spanish, with Biden and his vice presidential running mate, California Sen. Kamala Harris, dominating the airwaves.

“Un hombre como Biden sabe cómo sacarnos del hoyo en que estamos,” one woman says, referencing the pandemic. “A man like Biden knows how to get us out of the hole we’re in.”

Each day, meanwhile, brings records for early voting, another reflection of off-the-charts interest. (A less salutary measure is the run on guns and ammunition by all those fearing postelection violence.)

As of Saturday evening, more than 91 million Americans had already cast their ballots, well over half the projected election turnout. In Texas and Hawaii, the early vote exceeded all the ballots cast in those states in 2016. Several more states were topping 90% of their total 2016 vote.

In California, Johana Pineda was among those Saturday who weren’t waiting for election day. She cast her first-ever presidential ballot at a recreation center in Long Beach, a vote for Biden and — she hoped — peace and harmony.

“The country is fighting against each other,” the 20-year-old student said. “It needs to stop.”

A Stanford study of 18 Trump rallies held in the midst of the pandemic suggests they’ve led to more than 30,000 coronavirus infections and at least 700 COVID-19 deaths.

For Republicans, the gloomy outlook extends to the fight, or lack thereof, for control of the House.

The GOP had begun this election cycle hoping to win back control after losing it in 2018. Republicans need a gain of 18 seats — less than half the total Democrats picked up two years ago. But with Trump weighing down the party’s prospects, the best hope for Republicans appears to be minimizing their losses; in the worst case, that number could climb into double digits.

To a large extent, the dynamic reflects the forces that took hold in the midterm election, when Trump’s cratering support in the suburbs led to a Democratic rout; in Orange County alone, Republicans lost four House seats, turning its congressional delegation blue for the first time since the 1930s. This time, Democrats are driving even deeper into territory that was once reliably red, targeting House seats in Missouri, Nebraska and Texas.

With so much in the balance, surveys have found voters attaching enormous consequence to this election. A Pew poll this summer found more than 8 in 10 said “it really matters” who wins, the highest percentage in the last several presidential campaigns.

“We’re not just deciding whether to have a capital gains tax cut or some policy wonk decision,” said David Leland, an Ohio state representative and former Democratic Party chairman. “We’re deciding the future of America. The future of democracy, the future of our republic and what it stands for.”

Whatever their differences, that is something many on both sides of the country’s cavernous divide would agree on — and may keep fighting over well after election day has passed.

Times staff writers Noah Bierman in Washington, Melissa Gomez in Oviedo, Fla., Melanie Mason in Philadelphia and Joe Mozingo in Long Beach contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.