Even from childhood bedrooms, socially distanced students work to get out the vote

WASHINGTON — When Lauren Guzowski makes calls to potential voters in this election season, sometimes she also provides a bit of live music in the background — perhaps the guitar chords of “Stairway to Heaven.”

“I’ve got a little brother who loves his electric guitar,” she said. “So sometimes I’ll be phone-banking and you’ll hear a little Led Zeppelin.”

Guzowski, 19, is a sophomore at George Washington University. Like many students her age, the COVID-19 pandemic means she’s spending this semester not in a dorm room but back home, living with her parents in Pittsburgh.

Yet on top of online coursework for her political science degree — including a “very topical” class called “The American Presidency” — Guzowski works as deputy director of campaign operations for her school’s College Democrats chapter. Amid parents walking into her room unannounced and, yes, the occasional guitar solo, she’s spending her quarantine digitally organizing “get out the vote” efforts for campaigns across the country.

“My field office is my bedroom,” she said.

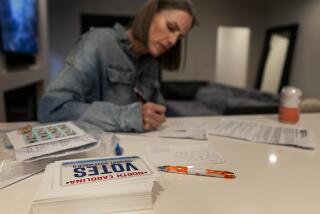

Guzowski is not alone. Young people nationwide — cooped up indoors, their social lives, work, school and housing disrupted — have spent the weeks before Nov. 3 making calls, sending texts and even hand-writing letters to influence voters in what some see as a potentially generation-defining election.

Most of the young activists The Times spoke with were Democrats. This tracks with polling from the nonpartisan Pew Research Center, which in mid-June found that 68% of registered voters between 18 to 29 support former Vice President Joe Biden, the Democratic nominee, versus 28% who support President Trump.

With his unexpected surplus of free time, 22-year-old Dylan Cohen, a recent graduate of USC, read up on politics and, working through a volunteer group called Postcards to Voters, wrote dozens of letters to Georgia voters in support of Democrat Jon Ossoff’s campaign to unseat Republican Sen. David Perdue. He also applied to be a poll worker, but hadn’t yet heard back.

“If I were still a senior in college and everything was normal, and I could have chosen between spending 45 minutes to go get drinks with a friend at a bar or hand-write letters, I would have just gone to the bar and gotten beer,” Cohen said.

Cohen’s cross-continent outreach — from his parents’ house in Malibu to voters in Georgia — is standard for pandemic-era campaign work, especially among Democrats. Unlike many Republicans, Democrats generally consider in-person door-knocking a potentially deadly tactic amid the coronavirus contagion, and many campaigns have moved their efforts online — meaning that anyone, anywhere, can hop on to canvass voters virtually.

“Before, if the campaign was doing a phone bank, they would have just done it in person [and] I would not have been able to join,” said Tyler Kusma, a George Washington University senior who’s moved home to Pennsylvania. “Now it’s a Zoom call, so it doesn’t really matter if I’m from Scranton or down the road.”

That flexibility means Kusma, 22, who’s president of GW for Biden, can pick and choose online which other campaigns to help. In addition to supporting his local member of Congress, he’s texted or called voters in Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana and Texas on behalf of various candidates on those states’ ballots.

With location no barrier to entry, choosing where to volunteer becomes a more strategic decision.

Agnes Mok, a senior at Pomona College who moved to Washington, D.C., after her classes went online, chose to work with the liberal super PAC Flip the West after deciding that “flipping the Senate was going to be more important … than [volunteering for] other individual candidates,” she said. David Pernick of Silver Lake said he chose “empirically” to phone-bank for Iowa Senate candidate Theresa Greenfield, the Democrat challenging Republican Sen. Joni Ernst.

“I’m like, ‘OK, what are really close races in really small states?’ Because the smaller the state, the more impact each call has, right?” said Pernick, 29, who had time to spare after his test preparation and tutoring business slowed down. “I was thinking Iowa versus Montana, and I just, flip of a coin, decided to go with Iowa.”

For other young volunteers, campaign work is a way to stay socially active. Rhea Trainson, who leads Pennsylvania college outreach for the progressive organizing group Swing Left, said digital campaign events offer a chance to connect with friends and chat with peers.

“We’ve really started advertising these as parties in their own way, and having fun themes for events,” said Trainson, 21. “I know one of my favorite events that I hosted was a Timothée Chalamet costume contest and letter-writing event.”

For some students, moving back home means sharing a roof with family members of different political persuasions. Guzowski said her father is a Republican, and family discussions can sometimes get “a little heated.”

“I think they’re really worthy discussions,” she said. “[It’s] very different than being on a college campus with a bunch of other poli-sci majors.”

While pandemic-related adjustments have in some ways made volunteering easier, voting itself can be more complicated for college and post-college young people who’ve relocated. For an extreme case, consider Iris Chen.

Chen, a sophomore at Atlanta’s Emory University, took the semester off and moved to a cousin’s house in South Lake Tahoe to work, hike and explore. In late July, she filed to receive her Georgia absentee ballot at the Tahoe house, but later discovered that the area is too rural and isolated to receive mail, as a worker at a local post office explained.

Chen’s ballot was delivered to Tahoe, then bounced back to Georgia. She requested a second ballot, and drove to Sacramento for an affidavit swearing she wouldn’t use the first one, signed it and faxed it back to Georgia. A state website showed that a second ballot was shipped to Sacramento on Oct. 7.

Chen hadn’t received it by Friday, more than three weeks later. Meanwhile, she’d bought plane tickets to fly to Atlanta for in-person early voting; Friday was the last day to do so. “It’s much more difficult [to vote] than I thought for my first election,” she said. But once she got to her polling place in Atlanta, “it went really smoothly.”

Even for students who still live in the state where they’re registered, relocations can upend voting arrangements.

Chris Wig, chair of the Democratic Party of Lane County, Ore. — home to the University of Oregon, which is primarily online through the winter — said the party is seeing “a diffusion of Democratic voters” away from the county as some students move home and re-register there. Because Lane County is safely blue, Wig said, the shift of pro-Democratic students to other areas of the state can only help the party.

Not all college towns are experiencing such changes. William Ellis, the Republican Party chairman in Monroe County, Ind., said that enough Indiana University Bloomington students have remained on campus that he hasn’t “seen any changes to the student dynamic with voting.” And Scott Grabins, Republican Party chair in Dane County, Wis., said that the College Republicans of the University of Wisconsin-Madison “continue to be engaged with campaign activities.”

But for many of America’s youngest voters, the pandemic has redefined if, how and why they engage with politics.

“I would offer a broad apology for how many phone calls people are getting, … but I think it’s really worthwhile work,” Guzowski said. “I hope that people know that, a lot of the time, it’s young people and kids who are on the other end of those phone calls, doing the best that they can.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.