Joe Biden is counting on Nevada. Has the COVID-19 pandemic hurt his chances?

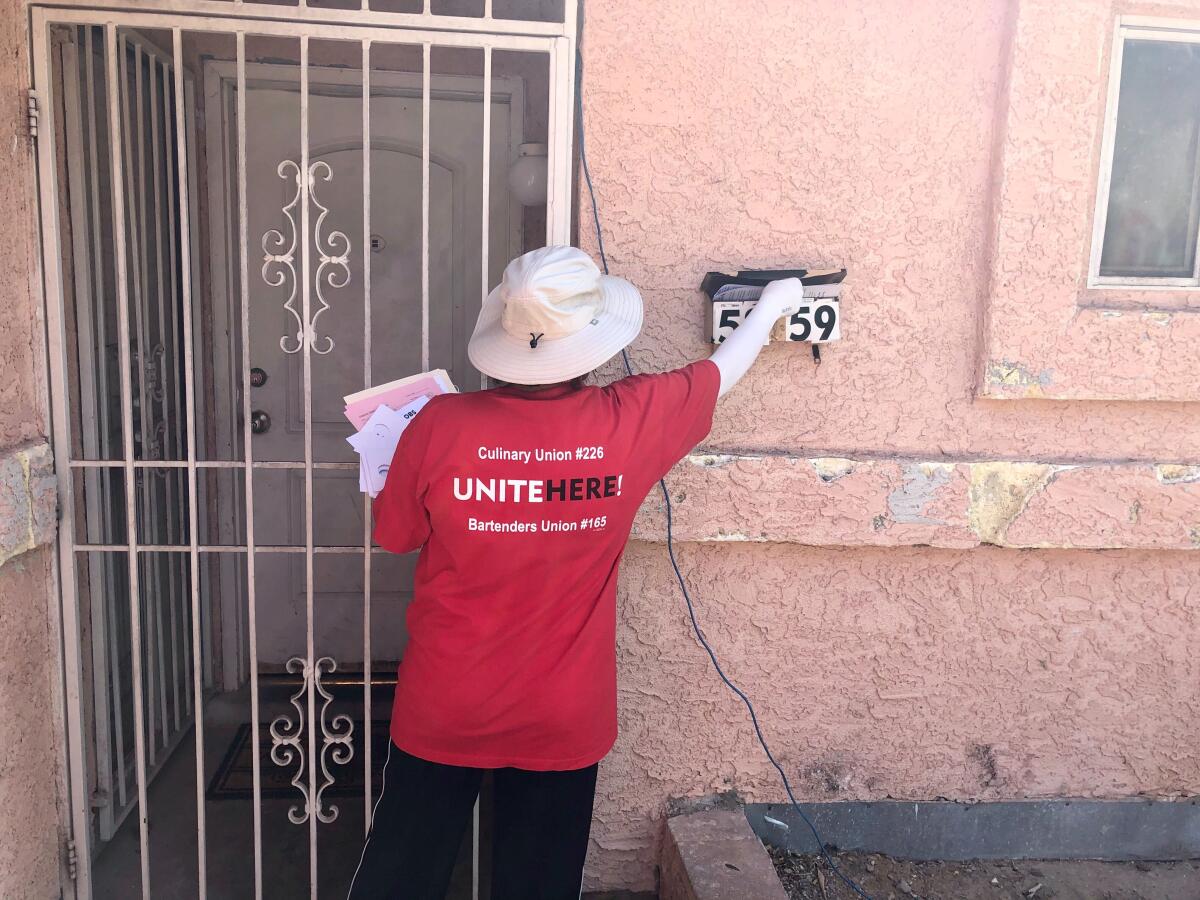

LAS VEGAS — On a blazing hot afternoon, two canvassers recently went door to door in a working-class neighborhood of east Las Vegas, bearing masks, campaign fliers and the weight of Democratic worries.

Up and down stairs, across baking driveways, past thirsty lawns, Maria Magana and Atilano Salgado took turns asking voters in English, Spanish and a combination if they would support Joe Biden for president.

“Perfecto,” Magana responded when the answer was yes. Then she entered the information on a tablet cradled in her arm.

Nevada — once reliably Republican but more recently Democratic — is something of a question mark in these closing weeks of the campaign.

Polls taken before President Trump’s hospitalization with COVID-19 gave Biden a small but consistent lead over the incumbent, who narrowly lost the state four years ago.

However, the great strength of Democrats — the work of political foot soldiers like Magana, 45, who helps tidy the casino at the MGM Grand hotel, and Salgado, 35, a line cook at Guy Fieri’s Vegas Kitchen & Bar — has been significantly reduced as a result of the pandemic.

Trump pronounces himself fit, as his press secretary, Kayleigh McEnany, and other members of his team announce they’ve tested positive for coronavirus.

For months, Democrats failed to conduct the intensive voter registration and face-to-face conversations that helped flip the state in the late 2000s from red to blue.

“People were sheltering at home. Nobody was going door to door. If you stood outside a supermarket, people would think you’re crazy,” said D. Taylor, the head of Unite Here, the national parent of the local Culinary Union, which runs the state’s most powerful political operation.

Although Democrats say they’re making up for lost time — using measures that ensure it’s safe again to knock on doors and finding creative means of engaging voters on social media and other outlets — they also say the contest is closer in Nevada than is comfortable.

Privately, they fret over Biden’s lack of personal visibility in the state — he has not been to Nevada since campaigning in February ahead of its caucuses — even as they condemn Trump for holding large-scale rallies last month in Reno and Las Vegas. Biden’s running mate, Sen. Kamala Harris of California, held a drive-in voter mobilization event in Las Vegas on Friday.

Republicans say Democrats have good cause for concern.

“Nevada’s been a tough state for us going back 16 years,” said Rick Gorka, a national Republican Party spokesman who served as a Las Vegas-based strategist for John McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign. “But a combination of events with a combination of candidates has put Nevada squarely in play, which should really scare Democrats.”

Nevada — the sum of cosmopolitan Las Vegas, its mini-me, Reno, and vast stretches of rural conservatism — has a history of close elections.

Harry Reid, arguably the most powerful lawmaker the state ever sent to Washington, lost his first try for Senate by 624 votes and once won reelection by just 428. With the exception of Barack Obama’s two comfortable victories, no presidential candidate since 1988 has carried Nevada by more than 4 percentage points; Hillary Clinton won by 2.4 points, or about 24,000 votes out of 1.1 million cast.

Typically, Democrats prevail by out-registering Republicans and out-hustling them to make sure their partisans vote — especially Latino, Black and Asian American residents of Las Vegas and its sprawling surroundings. While registered Democrats continue to outnumber Republicans both statewide and here in Clark County, the GOP narrowed the gap a bit over the summer by resuming its canvassing weeks before the Culinary Union took to the streets again in August.

“We’ve been out in the neighborhoods multiple times … working through the universe of voters we need to hit,” said Jeremy Hughes, regional political director for Trump’s reelection campaign.

The Biden team, which just resumed on-the-ground canvassing, said it compensated for the lack of face-to-face contact by emphasizing “relational organizing” — that is, reaching out to voters through networks of family, friends and other personal contacts. That can be even more effective than door-knocking, said Shelby Wiltz, a Biden strategist, “because it comes from someone you know, someone you trust.”

In addition to phone calls and texting, the campaign has used social media — trying things such as art shows and online ice cream socials — to expand its reach. When Harris hosted a small community gathering last month in Las Vegas, nearly 200,000 people viewed a post on Facebook Live, according to the campaign.

Biden and his allies have also spent more than $9.7 million on television commercials since mid-March, when the former vice president effectively clinched the Democratic nomination, roughly twice what Trump and his supporters have spent, according to Advertising Analytics, a firm that independently tracks campaign spending. Since Labor Day, the Biden campaign has outspent Trump’s by nearly 5 to 1.

Still, Taylor insists there’s no substitute for one-on-one conversations.

“You’ve got to get on the doors,” he said. “TV and radio talk to people. [They don’t] answer their questions.”

So on a 100-degree day in Las Vegas, Magana and Salgado were among 200 canvassers going block by block statewide, visiting preselected Democratic households to gauge support for Biden.

(In Las Vegas, they also pitched a measure requiring businesses to rehire workers furloughed amid the pandemic rather than replace them when operations resume. In mid-March, when the economy largely shut down, 98% of the Culinary Union’s roughly 60,000 members were laid off. Today, around half are still out of work.)

At each stop, after handing over masks and literature and stepping back from the door, Magana and Salgado logged the status of every voter who responded to their knock, so another wave of canvassers can follow up. “If they’re leaning or undecided, we’ll see if they’ve made up their minds,” Salgado said. “If they support Biden, we’ll make sure they vote.”

The union hired its own epidemiologist and industrial hygienist to create a safety plan and has shared the protocol with other unions and progressive organizations, hoping they soon get back to door-knocking. (Reid, the retired Democratic leader in the Senate, is quietly raising millions to boost the effort.)

Democrats have advantages they lacked four years ago. With control of the statehouse in Carson City, they pushed through laws making it easier to vote absentee and allowing same-day registration. A federal judge rejected a lawsuit by the Trump campaign seeking to block the changes.

Many supporters of Biden and Trump fear violence is likely in November. Each side blames the other.

But there are important differences from 2016, apart from COVID-19.

In 2016, Nevada was not just a presidential battleground. There was also a fierce contest to replace Reid in the Senate, which drew money and attention from Democrats throughout the country. Although that helped Clinton win and allowed the party to retain Reid’s seat, some worry the results may have left Democrats taking the state for granted — especially after winning it in three straight presidential elections.

Rebecca Lambe, a longtime party strategist, said Biden supporters needn’t think back far to appreciate the danger of complacency. She raised a cry certain to discomfit partisans.

“We don’t want to be the new Michigan,” she said, referring to parts of the supposed Democratic “blue wall” that crumbled in 2016, costing Clinton the White House. “We don’t want to be the new Wisconsin.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.