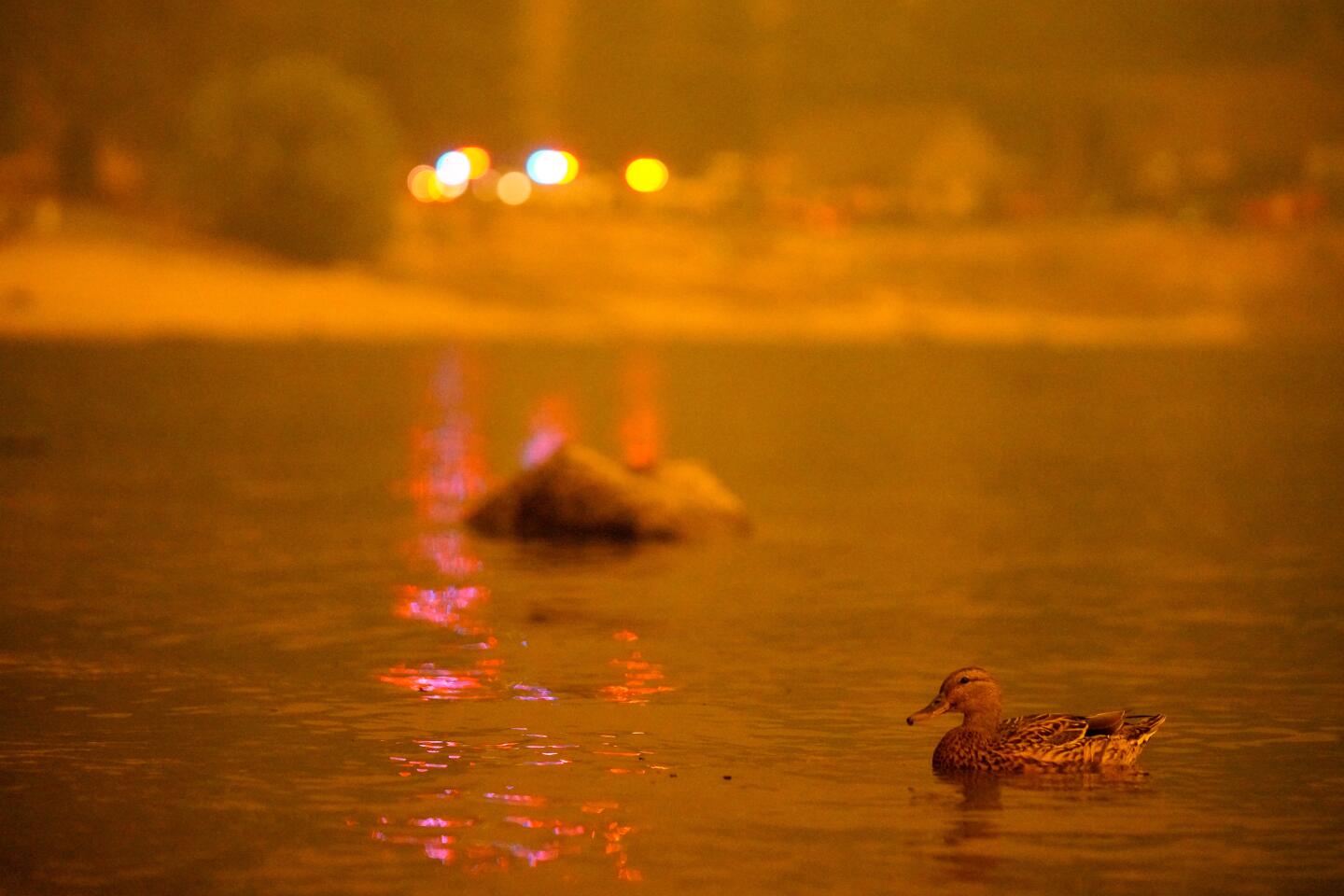

Wildfires have burned over 5 million acres in the West. Are they too big for Washington to ignore?

WASHINGTON — With massive wildfires across the West burning more than 5 million acres and displacing tens of thousands of people, Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon says this is the moment for Congress to reform the nation’s fire management policies, or brace for more Septembers like this one.

“I want to be able to call this the day the Senate got serious about fire prevention,” the Democratic senator said Monday in a floor speech.

Residents in California, Oregon and Washington — many still under evacuation orders or living under a layer of smoke and ash — will probably have to wait longer to see that day.

Feeling new urgency from a historic wildfire season, Western Republicans and Democrats have put forward legislative proposals for addressing the region’s forests, which are unnaturally overgrown thanks to decades of fire suppression.

The crisis has brought to the surface divisions among Democrats about how to address the problem — rifts that are only likely to become more acute if Democrats win the presidency and the Senate next year, and push climate legislation through Congress.

On Thursday, Wyden unveiled his plan — a set of changes that would require the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management to use prescribed fire more frequently to preemptively burn off excess vegetation that can otherwise become tinder for out-of-control blazes. The bill would direct new federal funding to this effort, which has been held back by lack of money, limited manpower and risk-averse federal officials.

Another proposal, a bipartisan bill from Sens. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) and Steve Daines (R-Mont.), presents a vastly different approach. It would create new exemptions to the nation’s bedrock environmental law, the National Environmental Policy Act, limiting public review of forestry projects to speed up the removal of small trees and shrubs.

It has been endorsed by both California Gov. Gavin Newsom and the American Forest Resource Council, a group that represents timber interests. But most environmental groups view it as an attempt to lock the public out of decision-making, and it’s likely to face resistance from progressive Democrats in the House.

Crews protecting the Mt. Wilson Observatory from the Bobcat fire had a “good night last night.” Meanwhile the fire turned northeastward.

“I don’t think the House of Representatives will support major new incursions into environmental laws right now,” said Rep. Jared Huffman (D-San Rafael). “That’s what the Senate bill is.”

House Democrats plan to vote next week on an energy bill that would promote electrical grid resilience efforts to reduce the likelihood of transmission lines starting fires. It would also require the Environmental Protection Agency to research the impact of smoke emissions from wildfire and provide grants to help communities mitigate the smoke. Several Democrats are hoping to add their own proposals, including other plans to strengthen the electrical grid. Democrats have not yet decided which proposals might be added or get an amendment vote.

Policy differences aside, there are plenty of reasons to be skeptical that even the worst fire season on record will force Congress to act.

There are other pressing issues before lawmakers. In addition to avoiding a government shutdown this month, Democratic and Republican leaders in the House and Senate remain at an impasse over how to help Americans who’ve lost their jobs during the pandemic. Struggling industries are begging lawmakers for a bailout. And the presidential election is less than two months away.

Disastrous fire seasons have come and gone without federal legislative action. In 2018, wildfires killed more than 100 people and burned more than 1.8 million acres in California, a record that has since been broken by this year’s infernos. But when fires the following year proved less destructive and deadly, Congress’ interest in overhauling the country’s policies waned.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Even if the Democratic-led House and Republican-led Senate each passed separate fire bills this year, they would have to rectify the differences and get Trump’s signature by the end of December, an exceedingly unlikely possibility. Still, any agreement or compromise reached this year could form the building blocks of a bill in 2021.

Wyden believes there’s reason for hope.

“I do think this year is different,” he said. “For days and days my small state, unfortunately, has led every newscast in America. ... I’ve had a tremendous number of people in the Congress come up to me who had no idea these fires had gotten so out of hand.”

Experts have warned for years that the United States needs to completely change its approach to wildfire.

Decades of trying to stamp out every fire to protect the increasing number of homes built outside of cities in wildfire-prone areas has left forests crowded with vegetation. Combined with the increasing temperatures and prolonged droughts caused by climate change, this has contributed to the alarming scale of the fires the West is experiencing now.

Most fire scientists agree that there’s no such thing as preventing wildfires. But there is growing consensus that certain interventions, such as prescribed fires, can reduce the severity of blazes.

Hardware stores have seen a run on portable air purifiers as smoke from the Bobcat and El Dorado fires continues to blanket Southern California.

Wyden’s bill focuses narrowly on this issue. It would set aside $600 million annually, split between the Department of Interior and the Forest Service, to pay for controlled burns on federal, state and private land. Under the bill, these agencies would be required to increase the number of acres burned during the off-season each year. There would also be a $100,000 incentive program to encourage state and county governments to carry out their own burns.

Another part of the bill would shield federal employees planning or conducting a prescribed burn from a range of lawsuits, except in cases of gross negligence.

Craig Thomas, a California conservationist who has spent years advocating for more prescribed fire, called this change “incredibly important.” One of the reasons controlled burns are still relatively rare in the West is that federal employees fear they could be held personally responsible if the blaze got out of control.

“It all comes down to the fact that these people are following the rules, they have the training, and they’re trying to benefit us,” Thomas said of the firefighters who oversee controlled burns. “Why have them terrified?”

Feinstein’s proposed legislation also identifies poor forest management as a problem, but it places much of the blame on environmental regulations, a position that Republicans and the timber industry have advocated for years. An analysis of the bill by the Wilderness Society, a conservation group, found that it would set few limitations on the number of acres that could be logged without environmental review and would give the Forest Service emergency legal authority to bypass public input for certain activities, including the removal of burned trees after a fire, known as salvage logging.

It’s time for the governor to start blaming mismanagement of the forests as much as climate change for these horrendous wildfires, columnist George Skelton writes.

It would also create a $100-million grant program to increase the number of biomass facilities in the U.S., propping up an industry that generates heat and electricity — and carbon dioxide — by burning dead and dying trees that have no commercial value.

This would “help make harvesting dead trees more commercially viable, incentivizing businesses to step in and help reduce the fuel load in our forests,” Feinstein said Wednesday during a Senate committee hearing.

While Feinstein’s bill is unlikely to get much support from progressives in the House, a wildfire bill that has been lingering there is just as unlikely to see much enthusiasm from Republicans in the Senate. Introduced last year by Huffman and Sen. Kamala Harris of California, it would provide $1 billion annually to direct communities to develop plans to protect themselves against wildfires, including improving evacuation routes, increasing resiliency of homes and clearing brush.

Susan Jane Brown, an attorney for the advocacy group Western Environmental Law Center, said lawmakers across the West are feeling under pressure to do something about fast-moving fires that have incinerated small towns and polluted the skies. But she urged caution.

“There is some merit in really taking a look at these bills and picking the pieces we think work and repackaging them,” she said. “But we have to be really careful about overselling simple solutions. I don’t want to make bad policy because we’re scared.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.