Pennsylvania’s blue-collar voters see danger — and back Trump

WILKES-BARRE, Pa. — There are no mass protests over racial injustice or police brutality here, and the only fires or violence Wendy Williams encounters are on television and online. Yet the spotty images of unrest in faraway Portland, Ore., and Kenosha, Wis., linger in her mind.

If anything, she’d like President Trump to crack down harder, to follow through on his threats to send more troops to quash the protests. She wishes he didn’t say so many inflammatory things, yet resents those who label him a racist.

“There’s always been racism. There’s always gonna be racism, but it’s not him that’s doing it,” Williams, a white, 53-year-old stay-at-home mom, said outside a Walmart. “It’s the Democrats and the media that are getting it out there and keeping it out there. And if the riots don’t get taken care of, it’s just making it worse.”

Williams said she did not vote in presidential elections before Trump came along in 2016. Now, she is an essential part of his 2020 coalition. She lives in Wilkes-Barre, in blue-collar Luzerne County, one of three Pennsylvania counties that flipped from blue to red in 2016 and helped give Trump the state — and a narrow electoral college victory.

Trump’s racially loaded calls for “law and order” in the face of mostly peaceful protests, and his dire warnings that Democratic nominee Joe Biden will “demolish the suburbs,” have alienated some voters in the actual suburbs, where Black and Latino populations are growing and many educated white women are abandoning the Republican Party.

But Trump’s appeals to the grievances of white supporters — including his recent order to purge the federal government of racial sensitivity training — appear to be resonating with voters in down-at-the-heels industrial cities such as Wilkes-Barre, where his campaign hopes for a surge of white working-class voters.

Trump’s promises to crack down on “chaos” in cities “actually play better with voters that are far away from the unrest,” said Patrick Murray, director of the Monmouth University Poll.

Polls show Biden leading Trump by 5 percentage points in Pennsylvania, according to an average compiled Friday by FiveThirtyEight.

Both campaigns agree that Trump’s best chance to overtake Biden in the state is to get more rural and small-town voters to counter Biden’s strength in and around Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

Luzerne County is overwhelmingly white, although it has grown more diverse in the last decade. Black and Latino residents account for 21% of the population of 317,000.

Most residents live in single-family houses or duplexes, many with freshly mowed lawns and a few stray tires, well-used porches and American flags. Railroad tracks, Catholic churches and views of billowing smokestacks and the Pocono Mountains are never far.

The old Sears and Bon-Ton stores in the Wyoming Valley Mall are vacant, along with much of the food court. A pair of universities have taken over many of the buildings downtown. Most shopping takes place at big-box stores and supermarkets at the top of the hill.

Interviews with voters here largely confirm what polls say about Trump. People either love him or hate him, with even fewer persuadable voters than four years ago, despite a flailing economy and a coronavirus outbreak that has killed 190,000 Americans and continues to spread.

Those who like Trump tend to overlook or forgive his flawed handling of the pandemic, along with the scandals and character issues cited by Biden supporters. Many of Trump’s supporters get their news from Trump-friendly sources and agree with the president that Biden is too far left or mentally frail, ignoring Biden’s efforts to reassure voters that he is neither.

Trump “is the first one, the first president in my lifetime — and I’m 53 — to actually keep the promises that he said he was going to do,” Williams said. Research shows Trump has fulfilled fewer of his campaign promises than other recent presidents.

Those who oppose Trump say they are frustrated that his supporters don’t see that he’s “the biggest phony that ever existed,” as Cynthia Bhagat put it.

The 80-year-old retiree volunteered for Hillary Clinton in 2016 and plans to make calls for Biden. But Bhagat said she no longer recognizes her community, and not just because the coal mines that dominated the region decades ago have been replaced by warehouses for Adidas and Chewy pet foods.

“This was all Democratic when I was born and it’s now Trump country and I don’t understand it,” she said, pointing to Trump’s supporters among her cousins as evidence of that shift.

She said her children, whose father was northern Indian Sikh, faced “very subtle in-grown racism” when they were growing up, and she sees racial prejudice as pernicious.

“Trump just presses that button,” she said.

Ashley Murray, a 33-year-old nursing home employee, sees a similar dynamic, even as she notes the irony that at least some Trump voters here helped put President Obama in office twice.

Trump is “the part of them that, because most of the county is basically white, and they feel like he’s saying things that they want to say, doing things that they want to do,” she said. “They feel like he’s standing up for them, even though he’s not for them.”

Appeals to racial and cultural identity here predate Trump’s rise.

In 2006, Lou Barletta, then mayor of the second-largest city in the county, Hazleton, championed an ordinance that he said was designed to make life intolerable for immigrants who came to the country illegally. It included provisions to fine landlords and deny permits for businesses that hire them.

Courts ruled the ordinance unconstitutional, but Barletta was elected to Congress in 2010 and was one of the first House members to endorse Trump, largely on the issue of immigration. He left office for an unsuccessful Senate run in 2018.

Trump continues to rail against immigration this year but now uses his harshest rhetoric against protesters and Democrats. He argues that the country’s real race problem is bias against white, not Black, Americans.

“The Democrats never even mentioned the words LAW & ORDER at their National Convention,” Trump tweeted Thursday. “If I don’t win, America’s Suburbs will be OVERRUN with Low Income Projects, Anarchists, Agitators, Looters and, of course, ‘Friendly Protesters.’”

Biden has tried to make inroads here, delivering a recent speech in Pittsburgh about the unrest, and speaking often of his childhood in Scranton, just north of here.

Trump has come more often, holding a campaign event in nearby Old Forge the night Biden accepted the Democratic nomination and sending Vice President Mike Pence soon after. Both candidates visited Shanksville on Friday, the 19th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, for a memorial event.

Trump’s focus on the county, while potentially boosting support, raises questions about whether the president’s campaign is as confident as it claims.

Democrats hold advantages in new registrations and mail-in ballot applications, although Trump overcame the registration advantage in 2016. Even if Trump repeats his victory in Luzerne, Biden can make up the difference with increased turnout in Philadelphia and the surrounding suburbs.

Michael Truchon, a retired prison maintenance worker, applauds the president for putting “the hammer down” to stop people from tearing down monuments of Confederate generals and others.

Truchon believes racism exists but says “the statistics are being skewed” when it comes to police shootings.

“They’re oppressed by the Democrats,” he said of Black Americans. “They have the same opportunities I have.”

Tim Merli, 29, plans to vote for Trump after skipping previous elections. He said the president has no choice but to threaten the protesters.

“I understand where they’re coming from but, like, completely destroying something — that’s just going to make more anger and more retaliation and more problems to come,” he said while repairing a curb at the mall.

Some Trump supporters are uncomfortable with his rhetoric surrounding race.

Alicia O’Donnell, a retired business analyst, points to Trump’s work on sentencing reform as evidence he has helped Black inmates and said the president is simply offering to help cities deal with vandalism and violence when he calls for “law and order.”

“I just think he spews to Twitter quicker than he should,” said O’Donnell, who voted in 2016 for the Libertarian candidate and plans to vote for Trump this time.

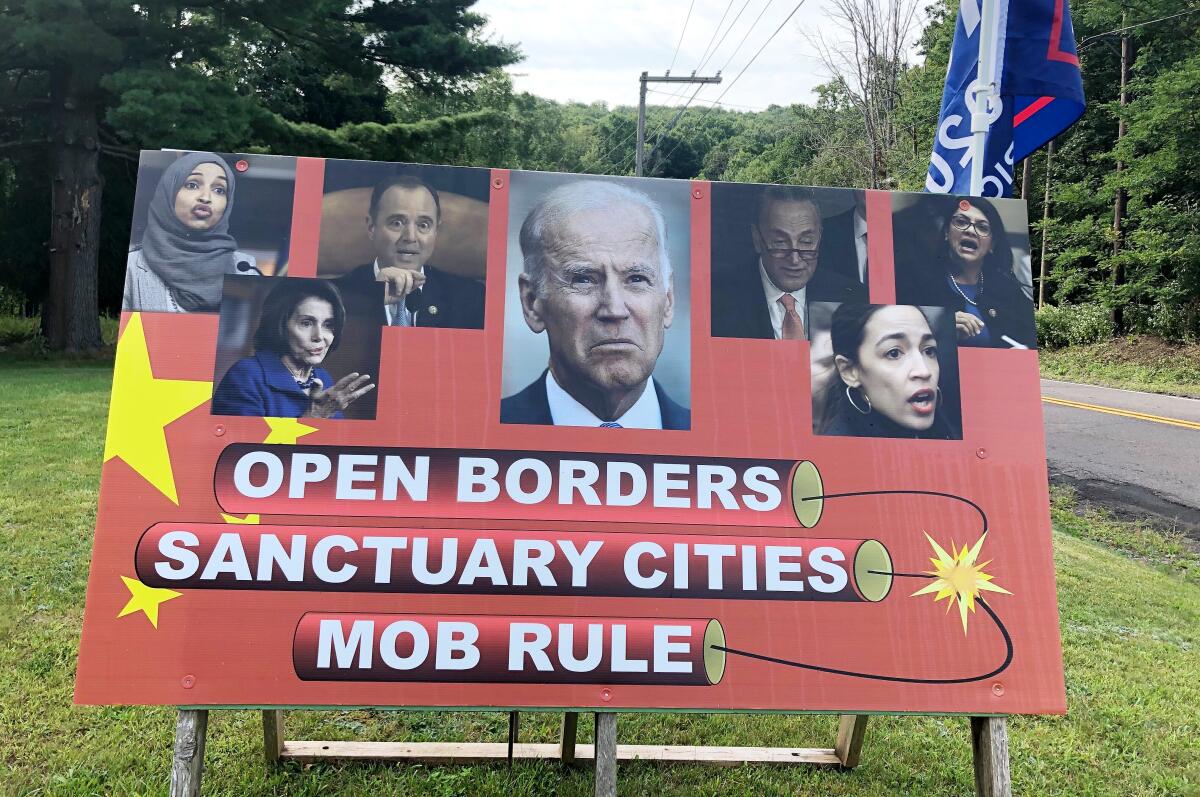

But in the hills overlooking the Susquehanna River, a highway is flanked with Trump signs and pro-police flags. A homemade sign shows a picture of Biden, scowling, surrounded by Democratic leaders and three of the four members of “the Squad,” prominent first-term liberal congresswomen of color.

“OPEN BORDERS, SANCTUARY CITIES, MOB RULE,” it warns.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.