COVID-stricken pastor could barely breathe. He kept fighting for the right of Black people to vote

After being hospitalized with the coronavirus, Rev. Greg Lewis returned home just before the April 7 primary and watched the fiasco unfold on television. Thousands of mainly Black voters risked their health to wait in line for hours to vote. Many more cast absentee ballots that were disqualified for technicalities.

The Rev. Greg Lewis could barely eat or get out of bed. He struggled to breathe. Doctors confirmed it was COVID-19.

Even so, the Milwaukee pastor persisted with his work helping Black parishioners vote. A couple of weeks into his illness, on March 26, he became lead plaintiff in a suit to postpone Wisconsin’s presidential primary because of the roaring pandemic — to no avail.

The next day, the 62-year-old was rushed to the hospital. “Baby, I’m dying,” he muttered to his wife.

From intensive care, Lewis kept working the phone, urging fellow Black pastors to do what they could to ensure voters could safely cast ballots.

“There was going to be some fighting on the way out,” he said.

Lewis recovered. He returned home just before the April 7 primary and watched the fiasco unfold on television. Thousands of mainly Black voters risked their health to wait in line for hours to vote. Many more cast absentee ballots that were disqualified for technicalities.

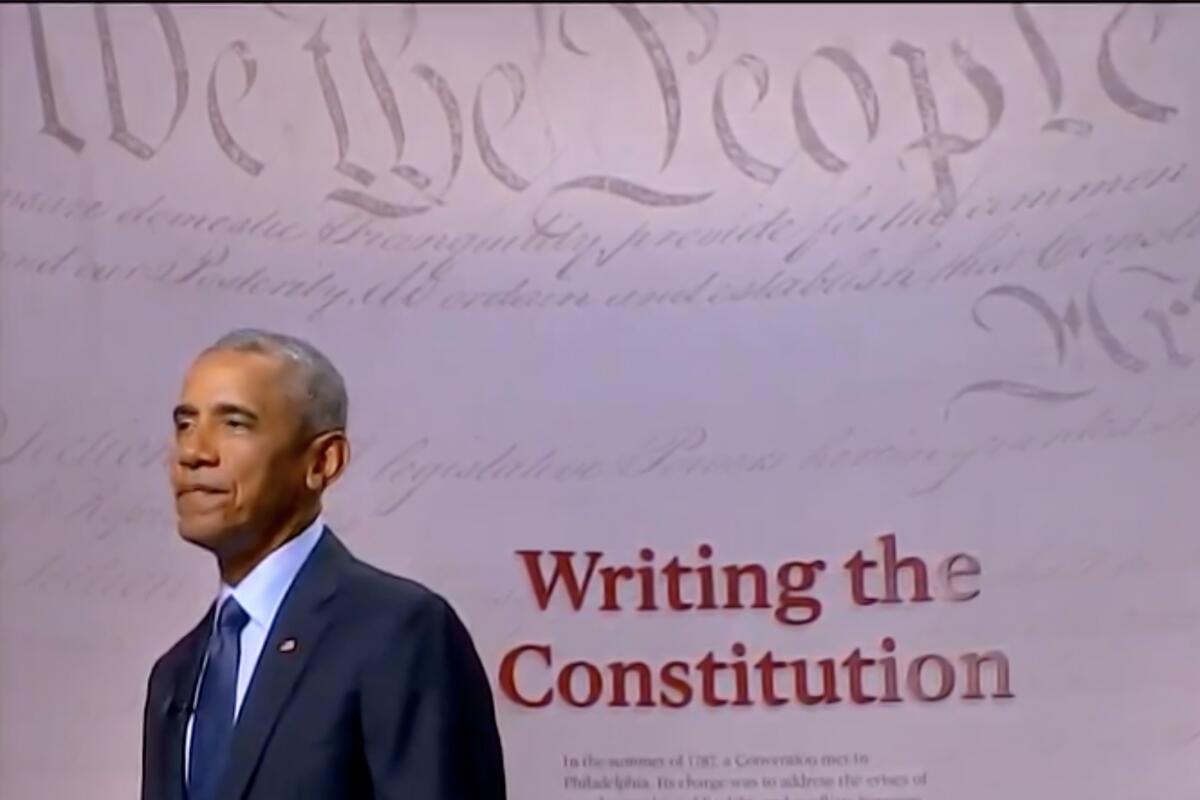

The pastor has spent much of his life fighting racial inequality, a central focus of the presidential campaign. Now he’s also at the vanguard of what former President Obama recently described as an existential fight to preserve democracy in the United States.

Lewis, the leader of Milwaukee’s Souls to the Polls organization, is alarmed by what he sees as a growing threat that many Black voters could be disenfranchised in Wisconsin, one of the battleground states that will decide the November election.

The mail delivery slowdown set in motion by Louis DeJoy, the Trump campaign donor who became postmaster general in May, is the latest in a long sequence of potential barriers to voting that have exasperated Lewis and other civil rights advocates for years in Wisconsin.

“This is all planned chaos,” Lewis said. “There’s a win-at-all-costs attitude that’s destroying our nation.”

Since Republicans took control of Wisconsin in 2010, they have imposed some of the nation’s most aggressive voting restrictions, including a voter ID law and reduced time for early voting.

To Lewis, it’s no accident that many of these measures have disproportionately affected Black people. He sees it as a variation on the Jim Crow South blocking Black voters from casting ballots if they could not recite a passage from the Constitution. He fears the pandemic, already taking a greater health toll on people of color, will make voter suppression worse than usual in November.

“Racism doesn’t change over the years, it just gets a little more sophisticated,” he said.

The danger of coronavirus contagion could deter millions of Americans from casting ballots in person on Nov. 3. President Trump’s unfounded charges that voting by mail risks tainting the election with rampant fraud have unnerved Lewis, who thinks some Black voters will conclude that dropping a ballot in a mailbox means it won’t be counted.

In his Democratic National Convention speech, Obama said Trump and his allies were “hoping to make it as hard as possible for you to vote and to convince you that your vote doesn’t matter.”

“That’s how a democracy withers, until it’s no democracy at all,” he said. “We can’t let that happen. Do not let them take away your power. Don’t let them take away your democracy.”

Lewis, the assistant pastor at St. Gabriel’s Church of God in Christ in Milwaukee, started organizing Souls to the Polls in 2012. It’s part of a loose-knit network of Black pastors in Wisconsin, Ohio and other states that started transporting congregants from church services to the polls when Obama was running for president.

Lewis has branched out, going door-to-door offering people not just a ride to the polls, but also help in registering to vote or securing the identification required to vote in Wisconsin.

Given many Black voters’ distrust of the political system, a pastor’s credibility is powerful, said Lena Taylor, a Democratic state senator in Milwaukee.

“They come from a perspective that makes people listen,” she said. “They’re the church, and people see the church differently.”

The pandemic has halted all the door knocking. Instead, Lewis and the other pastors reach out by Zoom and by phone to parishioners and their families and friends.

“Most of the organizing now is done at my kitchen table,” Lewis said. The pastors urge everyone to vote early.

Being a lifelong witness of poverty, racial injustice and segregation in Milwaukee put Lewis firmly on the side of Black Lives Matter protesters who took to the streets in hundreds of cities after the May 25 killing of George Floyd in police custody in Minneapolis.

The social upheaval hit close to home last month when police shot another Black man, Jacob Blake, in Kenosha, Wis., touching off demonstrations that turned violent in a small city an hour’s drive from Milwaukee.

Lewis’ hope is that stronger turnout of Black voters in Milwaukee will result in the election of officials who will help Black neighborhoods like his own — long suffering from higher unemployment and worse healthcare than in white sections of town.

“Milwaukee’s Black folks are in serious condition,” he said. “We are in dire straits.”

Lewis was raised by Fannie Lewis, a single mother who moved to Milwaukee from Louisiana in the 1950s. She was active in the union at the Master Lock factory where she worked. She once was arrested in a skirmish over someone crossing a picket line.

“My mother was quite a law-abiding citizen, but she really believed in the union, and she stood up for what was right for the workers,” Lewis recalled.

His awakening to racial injustice came at age 9, during the Milwaukee riots of 1967. Outbreaks of violence were flaring up that summer in cities around the country in response to police brutality and racial discrimination.

From his home on North 15th Street, Lewis heard the gunfire when Clifford McKissick, an unarmed Black 18-year-old neighbor, was shot in the neck and killed by police as he was entering his family’s house. Police were searching for young people who’d been tossing Molotov cocktails into a paint store down the street.

Lewis still remembers McKissick’s mother screaming, “Oh, they shot my baby!”

“That really never left me, that feeling of helplessness,” he said. “Clifford McKissick was the first guy out of our neighborhood to go to college.”

Eight months later, when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, Lewis remembers his mother ordering him to not leave home as thousands of Black people filled Milwaukee’s streets to mourn and march. Now all of 10 years old, he sneaked out anyway, joining a crowd led by civil rights activist James Groppi, a white priest at a nearby Black Catholic church, St. Boniface.

“That’s where I got the spirit to be a community activist,” Lewis said.

His mother sent him across town to a junior high school where nearly all of his peers were white, many of them the children of cops and firefighters.

“It was very clear that I was not an equal to these people,” Lewis said. “I could never be a leader in that school.”

As Milwaukee’s industrial base withered and jobs vanished in the decades that followed, many white residents fled to the suburbs. Today the city is 39% Black, 35% white and 19% Latino.

After Wisconsin Republicans took full control of state government in the 2010 tea party backlash against Obama, Lewis started organizing Milwaukee pastors to promote stronger turnout of the city’s Black voters.

The Republicans quickly redrew the state’s election map. The gerrymander packed Democrats into a small number of districts, giving Republicans an edge in the rest of Wisconsin — and in effect diminishing the power of Black voters. By 2018, Democrats would win 53% of the votes in state Assembly races, but just 36% of the seats.

“It’s not a fair election system when one side has such a severe election advantage, and it was done intentionally,” said Barry Burden, director of the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

Under former GOP Gov. Scott Walker, Republicans went on to tighten voting rules, above all with the voter ID law.

It survived court challenges alleging racial bias; studies showed minorities were less likely to have a driver’s license or other forms of ID required to vote. The law took effect largely intact in 2016 and remains on the books.

Robert Spindell Jr., a Republican on the Wisconsin Elections Commission, denied the GOP was trying to suppress Black votes, saying ID was a safeguard against fraud. “In every single human endeavor, I don’t care what it is, there’s lying, cheating and stealing,” he said.

Anita Johnson has tackled the challenges the law presents for some Black voters in Milwaukee. She works for VoteRiders, a group that helps voters get ID in states that require it. Through churches and community groups, she learns who might need ID. She tells them to find their birth certificate, Social Security card and proof of residence and bring it all to the DMV. She provides a ride if necessary. Many don’t have a birth certificate, though, and it can be hard to get one.

“It’s sad that we should have to jump through hoops just to go exercise our right to vote,” she said.

Other dictates also depress voter participation. Early voting, which is popular among Wisconsin’s Black voters, has been scaled back to the last two weeks before the election, down from six in Milwaukee.

Ken Mayer, a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, said voter suppression in the state had reached historic heights. “I think that in 20 years, we will look back on this era as the second coming of Jim Crow when it comes to voting rights,” he said.

In the lawsuit to postpone the April primary, Lewis and his allies ultimately won a court order, upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court, requiring absentee ballots postmarked by election day and received up to six days later to be counted, adding about 80,000 votes to the final tally.

One of Lewis’ main goals in the run-up to Nov. 3 is to make sure voters fill out their mail ballots correctly so they don’t get disqualified — not inconsequential in a state that presidential candidates sometimes win by a sliver. Souls to the Polls volunteers are dropping off literature on neighbors’ front doors to explain how to vote early and follow ballot rules.

Voting by mail is just days away. Wisconsin’s absentee ballots, available upon request, will be sent to voters starting Sept. 17.

For those who prefer to vote in person, Souls to the Polls plans to offer transportation to balloting stations in buses and vans, but is still working out a protocol for plexiglass dividers, masks and social distancing.

“It’s such a battle to get people organized to get ready to vote, because there’s so many obstacles that we face here in Wisconsin,” Lewis said. “It’s just a mess, and it’s a travesty of justice.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.