Trump administration struggles to rally international support for new Iran sanctions

WASHINGTON — The Trump administration notified the United Nations on Thursday that the U.S. will — on its own — reinstate numerous sanctions to punish Iran after failing to rally international support to extend an arms embargo on the Islamic Republic.

In an embarrassing rebuke, numerous countries refused to go along with the United States on the embargo and now are questioning whether Washington even has standing to impose sanctions.

The dispute is the latest sign of the U.S.’ loss of global influence and growing international isolation in recent years.

In a formal letter delivered in person to U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres, Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo declared his government was activating a mechanism known as snapback sanctions, which will take effect in 30 days. He cited what he called persistent violations by Iran of the landmark 2015 nuclear deal that dismantled much of its nuclear infrastructure in exchange for sanctions relief and the unfreezing of Iranian assets in banks around the world.

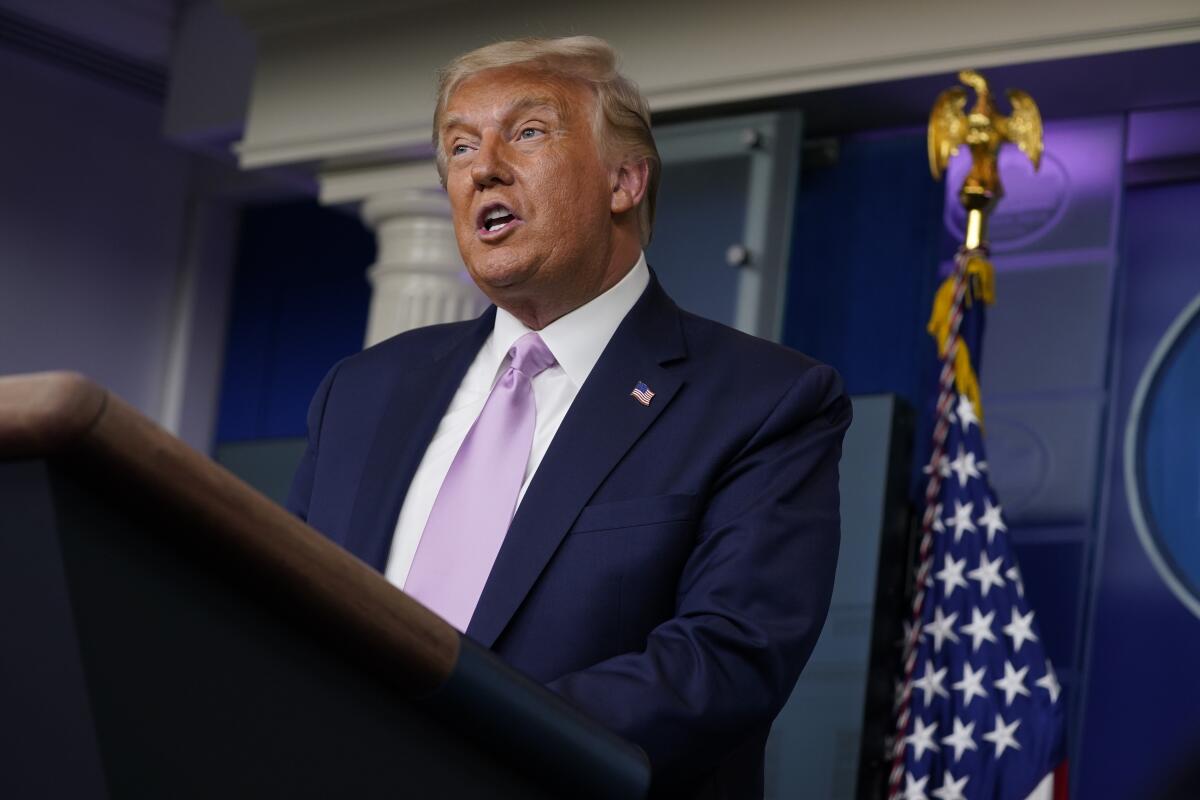

Pompeo was acting on instructions from President Trump, who announced the U.S. move Wednesday at the White House, where he reiterated his frequent criticism that the nuclear pact — signed by the Obama administration with Iran, Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany and endorsed by the U.N. — was a “terrible deal.”

Making good on a campaign promise, Trump withdrew from the agreement in 2018. According to several officials who helped draft it, withdrawing disqualifies a signatory from availing itself of its mechanisms, including the reinstatement of sanctions.

But Pompeo and other members of the administration refuse to recognize that.

“No country but the United States has had the courage to do this,” Pompeo told reporters at U.N. headquarters in New York after his meeting with Guterres. “America will not appease [Iran],” he added. “America will lead.”

He also threatened to punish countries with sanctions or other measures if they refused to join the U.S. action against Iran. “Our friends side with the ayatollahs,” Pompeo said.

Later Thursday, the foreign ministries of France, Germany and Britain reiterated their position that by withdrawing from the nuclear deal, the U.S. was disqualified from reimposing sanctions and said the U.S. move “is incompatible with our current efforts to support the” nuclear deal.

The administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign to economically cripple and diplomatically isolate Iran because of its nuclear ambitions and support for militant groups in the Middle East has had limited success. Tehran’s economy is reeling, battered additionally by the COVID-19 pandemic and drop in oil prices. But few countries have followed Washington’s lead in other areas, and the other governments that signed the nuclear deal continue to attempt to keep it afloat.

Trump has been largely dismissive of multilateral organizations, from the U.N. to NATO, leaving world leaders questioning whether the United States is a reliable partner.

Pompeo disputed that characterization. “President Trump leads from the front,” he said. “He’s prepared to take the courageous stands.”

Critics say Trump has little to show for his foreign policy efforts. Negotiations with North Korea, initially hailed as historic, foundered and have not curtailed the country’s robust nuclear program which, unlike Iran’s, includes nuclear bombs. Although Trump had a hand in new normalization talks between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, his vow to forge a peace deal between Israel and the Palestinians went nowhere.

“The floor is falling out from under our international credibility and faith in American leadership,” Tony Blinken, chief foreign policy advisor to Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, said in a recent interview.

The administration’s failure last Friday to win Security Council approval to extend a 13-year-old embargo on sales of conventional weapons to and by Iran symbolized Washington’s struggles. Only the Dominican Republic voted with the U.S.; 11 of the council’s 15 members, including France, Britain and Germany, abstained. Pompeo said Thursday the snapback sanctions will effectively serve as a wide arms embargo on Iran.

The Europeans, along with Russia and China, oppose escalating sanctions and criticize the U.S. attempt to invoke the privileges of a deal it has attacked and jettisoned, known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA.

“We have repeatedly said that the U.S. has already withdrawn from the JCPOA and therefore has no right to request the restoration of the U.N. sanctions regime against Iran,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian said at a briefing on Thursday in Beijing.

Iran, in response to the U.S. withdrawal from the agreement, began limited enrichment of uranium, a key step in producing nuclear material. U.N. inspectors, who previously issued several reports saying Iran remained in compliance with the agreement, now say they suspect some undeclared nuclear activity by Tehran.

Iran’s permanent representative to the U.N., Majid Takht-Ravanchi, spoke to reporters after Pompeo. He said the U.S. effort was “ridiculous,” based on “lies” and without legal foundation.

Republican lawmakers, meanwhile, along with some conservatives came out in favor of the sanctions effort, arguing that by one interpretation of U.N. resolutions, the U.S. retains its right to trigger the snapback.

“A snapback of sanctions would make the region and the world safer,” said Sen. Jim Risch (R-Idaho), who chairs the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. “The international community must resist the urge to postpone this necessary action yet again. The U.N.’s own credibility to deter further proliferation is on the line.”

Other critics said the Trump administration’s motive is to further undermine the nuclear deal.

“All of this is a gambit by the Trump administration to try to kill the JCPOA once and for all and to make it exceedingly difficult to resurrect it, hopefully when Joe Biden becomes president of the U.S.,” Wendy Sherman, a top U.S. negotiator behind the deal and former undersecretary of State, said earlier this week in a teleconference.

Richard Nephew, a sanctions expert and former State Department official who also helped negotiate the Iran deal, said the administration will probably be able to satisfy itself that it has triggered sanctions because the U.N. has “no real means” of blocking the maneuver.

“The United States believes that it has standing to do this and that is really enough for U.S. purposes,” Nephew told The Times on Thursday. “I don’t think they mind much whether others agree, because — in their view — there is no international arbiter capable of denying us that standing.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.